The World is a Carpet (33 page)

Read The World is a Carpet Online

Authors: Anna Badkhen

All of that had fit into the pannier of Baba Nazar’s donkey perfectly. In Dawlatabad, Abdul Shakur the yarn dealer had run his fingernail against the back of the carpet and studied the pile for mistakes and bought it for two hundred dollars, and then turned around and sold it to a dealer from Mazar for two-twenty.

That was about three weeks after Ramadan. By the time Qasim and Ramin and I hiked up the hummock in the drizzle of November, the loom had been dismantled and the beams put away and the loom room was stocked with dusty pyramids of large burlap sacks stuffed with hay, animal feed for the winter. The carpet was gone.

In its place was a little girl.

Her name was Sahra Gul: Desert Flower. Her face was pink and fat and smooth, and she was healthy, and her eyes were dark and vatic pools. She was born in the month of Mizan, two weeks after Thawra had finished her carpet. Boston midwifed. It was an easy evening birth by lamplight, and the moon had stared away the dust, and the sky was gold-speckled ultramarine. Amanullah was hanging out with some friends at the far side of the village that night. When he returned home, his third child was waiting for him.

He said to his wife: “Oh! You are two people now!”

When I met Sahra Gul, Thawra was holding her against her chest. She had swaddled her daughter in blankets and scarves and old adult clothes ripped into sheets. The weaver herself wore a sweater over her calico dress. Yet through all that cloth she could feel her daughter’s little heart go

thk-thk-thk

. Barely visible dimples of affection blossomed on the woman’s sunken cheeks.

“Are you going to have more children, Amanullah?” I asked.

“

Inshallah

. I’ll accept more.”

And he smiled his sly mustachioed smile and his strabismic eyes narrowed with mischief.

V

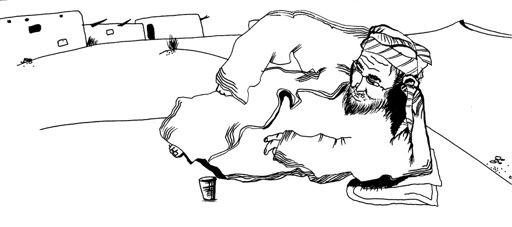

illagers crowded Amanullah’s bedroom. They squatted and sat and reclined, and their level of comfort and geography in the room as always corresponded to their status in it. Amin Bai sprawled by the old trousseau at the upper end, catlike and much pleased with my gift of Bushnell binoculars with twelve-power magnification and coated antiglare optics. They were sleek and black and the object of instant admiration by the men, most of all Choreh, who had stridden into the room urgent and high, and clasped my hand hard and slightly threateningly, and held it so for a long time and then said: “Next time, bring me binoculars as well.” And he looked me straight in the eye with his tiny frozen pupils, unblinking.

The Oqans were there to trade stories and to drink tea—because it was always good to drink someone else’s tea, because there was little else to do, and because their communality offered the villagers a sanctuary, however make-believe, from their stunning and stunningly malign land. Yet an ineffable brokenness blew through the room the way sand blew up the stoss slopes of the lunate dunes outside.

Something was askew about the greenish pallor of Zakrullah’s skin, his cavernous cough, his apathetic limbs hanging thin and limp from the left hip of Choreh Gul where she stood in the doorway. About the way Baba Nazar rummaged in his memory for a full minute before thinking of the name of his youngest, seventh grandchild. About the way Leila pranced past the squatting boys and men, and plopped down next to her grandfather, and tucked in her feet, and put a condom in her mouth, and blew it up into a balloon, let the air out, blew it up again, deflated it again, blew it up, repeated. “I’m dizzy I’m dizzy I’m dizzy,” she said. No one laughed. A boy maybe twice as old as Leila lit a cigarette in the corner. Baba Nazar shook his head and looked away. Children nowadays.

Next to Baba Nazar sat his nephew, Abed Nazar the soldier, home on leave from deployment in Kunar and trapped in the village by the weather for more than a fortnight. He had brought war to Oqa, on his cell phone. A video of an ambush that killed two American and four Afghan soldiers. A photo of Abed Nazar himself, with a rocket-propelled grenade launcher on the shoulder of his black uniform sweater, posing against the backdrop of the glaucous folds of a distant mountain ridge. A photo of an “American soldier, my friend,” squatting over a tin bowl of some kind of frontier chow, his camouflage sleeves rolled up to display colorful tattoos, of which the largest was a red and blue five-point star. Photos of another American soldier eating rice, smiling at the camera, his face sprinkled with acne, and of a third, at rest on a foldout cot under the large camouflage flap of a tent. I had seen such photos. I had been in such tents, in Iraq, in Chechnya. No one got out of them with his soul intact.

“Where do you like it better, Abed

jan

, Oqa or Kunar?”

“Kunar.”

“Why?”

“I like war.”

The young boys in the room listened with admiration, their mouths half open. Leila had let the air out of the condom and was now chewing on it.

“Every day war, every day war,” grumbled Baba Nazar from his spot by the stove.

“What do you think about it, Baba Nazar?” I asked.

“Nothing to think about. It’s war. Is war good?”

He opened the door of the

bukhari

and stared at the small hot fire in it and said that three days earlier an airplane had flown over Oqa without a sound. He said it had flown very low.

“Maybe it was a drone,” said Abed Nazar, who had seen such things. “Maybe they think Oqa is a Taliban village.”

“Well,” said Baba Nazar, and closed the stove door again. For a long time he said nothing more. Next to him, the frail and bony Sayed Nafas quietly rolled and rolled between his thumb and forefinger someone’s cigarette butt, and the stinking dregs of tobacco from the cartridge flaked down onto Amanullah’s bedroom floor.

• • •

Baba Nazar asked me to step outside with him. The wind was gusting fifty knots. Thistle skeletons hissed in the desert. From the northern wall of the house flapped the pelt of a desert fox the old hunter had trapped just beneath the hummock the day before. We slipped on wet clay.

“Anna,” Baba Nazar said. “We love you. We are glad you came from America to see us. But we have no weapons. We are worried about your security here, and I am worried about my security after you leave.”

I thanked him for his kindness and waited for more. A rooster crowed. A couple hundred yards away, the asthmatic Kizil Gul and her heroin-addict son, Abdul Rashid, were pitchforking thornbrush in tandem into a lacy wall of fodder. Boston shuffled by with her back straight like a cane. In outstretched hands she carried two loaves of freshly baked

sharbi

, bread kneaded with onions and sheep fat. Steam from her cooking pulsated in the wind like something alive, like a heart.

At length Baba Nazar said: “Anna, I know in the past I have invited you to stay. But I don’t think you should spend the night here.”

A deep breath, and suddenly I pictured us the way a bird would see us, a white dove cast off course, or a demoiselle crane perhaps halfway on its hallowed and time-and-again desecrated migration across the big slate sky: two people working, a woman carrying food, an importunate visitor, and an old man barefoot in his black galoshes, his glasses held on his head by string, his Soviet shotgun a poor match for the war around him. Five tiny and fragile figures in the sodden desert, a poor man’s carpet decocted out of an eternity of violence and generosity and grace. Each of us flawed, and so, complete. All of us woven into a time warp named Oqa.

T

he weather cleared that afternoon. Wispy cirri slid about the pale and brittle autumn skin of the sky like half-formed afterthoughts. In the west, a cold lusterless sun gilded the Bactrian plains in an antique and tarnished glow.

Amanullah steered his motorcycle into that slanted light. He drove maniacally. He jumped over russet hassocks and charged rusty boulders and skidded on wet smears of ocher clay. He blazed through pink morass and blue puddles where once there had been paths, caromed through patches of slough. He sped up, took narrow irrigation ditches flying, slowed down, sped up again, zigzagged. The wheels of his motorcycle lost traction and regained it and touched off canted fountains of mud that bore bits of human and animal bone and flakes of pottery and fragments of metal and shreds of plastic, and this protean exhibit of Anthropocene specimens propelled past the subdued sunset and splotched back down in rapid-fire arches. I sat astride behind him, clinging to his waist with my one good arm, too scared by our mad flight to do anything but laugh. So I laughed. Amanullah had adjusted his two rearview mirrors to watch my face, and each time I gripped him tighter he would beam and lean back against me as if to lie down on me and go faster still.

Amanullah was fleeing Oqa.

“I will take you to Kabul!” he shouted. “I will take you to Kandahar!”

Two other motorcycles debauched across the desert. Amanullah’s friend Asad, who had wrestled with him in the dunes the previous winter, drove Ramin. Qasim rode with Paidi, who was known mostly for having kidnapped a woman from Khairabad betrothed to someone else and marrying her—an immoral thing to have done, everyone agreed, though no one demanded that Paidi be punished for it. It was unclear whether the woman had had any preference one way or another.

The three drivers drag raced over gulches and gloppy fields and barren pastures, and whooped and careened into the wind. Loud and twitching psychotic circus riders reenacting the millennial bacchanal reckless men had performed upon this land since time immemorial, horseback and camelback and in tanks.

We could barely skylight in the south the quiet calligraphy of Karaghuzhlah’s naked orchards and breast-shaped clay roofs when the riders rumbled to a halt. An irrigation canal too deep and too wide for motorcycles to cross. A moat around Amanullah’s vagabond dreams.

We dismounted. Ramin and Qasim and I would walk the last two miles to Karaghuzhlah, spend the night, drive on south. But not Amanullah. Amanullah would have to ride back to Oqa.

Stuck, again.

“Well,” he said, and the rest of us shuffled in the slippery mud and repeated: “Well.”

Amanullah took a couple of long steps through the muck and stood astride the ditch, one foot on each loamy bank, facing west. Between his legs slow murky bubbles formed and burst upon a mocha-colored current that carried humus to thirsty fields. He beckoned to me. Then he grabbed me by the waist and lifted me up into the air and held me there long enough to give me three wet kisses on the cheeks and placed me on the southern side of the dike. Qasim and Ramin jumped across. Amanullah pushed himself off with his left foot and scrambled up the northern bank.

We stood on either side of the ditch and held our cold right hands to our hearts in the age-old gesture of gratitude and affection, of greeting and farewell. The sun had pitched its scarlet yurt in the west, where beyond Dawlatabad and Andkhoi and Turkmenistan and Iran, beyond an unfordable ocean, unreachable by donkey, lay America. To the south, evening dogs were barking, and boys were whipping the last sheep home from pasture through the clanging sheetmetal gates of Karaghuzhlah, and the wind carried ribbons of muezzins’ amplified calls like a salve to the desert. To the east, a purple darkness was spreading above the snow-streaked copper mountains. In a few hours a lidded waning moon would rise upon that dark curtain, and the Milky Way would follow, bisecting the sky, resplendent.