The Work and the Glory (79 page)

“She may need our support.”

She spun away from him. “I need your support!” she cried. Tears sprang to her eyes, catching her totally by surprise. She forced them back, biting at her lip.

Nathan was stunned. “I...” He stepped to her and enfolded her in his arms. “Of course,” he whispered. “I’m sorry. Come, lie back down.”

That was even worse. She turned around and buried her head against his shoulder. “I’m sorry, Nathan. I didn’t mean that. You’ve been wonderful. It’s just that...” The tears welled up again and she had to stop.

He rubbed her shoulders, then her back. “I know,” he said. “I know.”

They stood that way for several moments, then Lydia lifted her head. “You go. You’re right. Mother Smith needs all the support we can give her. I’ll just lie down for a while.”

He searched her face, then finally nodded. “Are you sure?”

“Yes. I’ll be fine now.”

He turned his head. She followed his gaze. Back near the stern, beyond the big side paddle wheels, they could see Mother Smith standing in the midst of the company. Many had their heads down, looking guilty. But one or two were talking to her, heads up and defiant.

“Will they never let up?” Lydia whispered. “She must be exhausted. Why can’t they let

her

rest?”

Mother Smith had gone the previous day to find temporary housing for some of the mothers and children who had gotten sick in the rain and cold. She had finally found, through sheer perseverance, an elderly woman who had agreed to take them in for a brief time. She had then stayed well into the night, talking to the woman about the restoration of the gospel. She had not returned to the ship until after two o’clock that morning.

“Because we’re all human, I guess,” Nathan said.

Lydia’s head snapped up and she stared at him, her eyes wide and still luminous from the tears.

He seemed startled, and she could see that his thoughts were racing. Then his face fell. “Honey, I didn’t mean you.”

Because we’re all human. And tired and pregnant and hungry and cold.

In an instant her mind was made up. She slipped an arm through Nathan’s. “Come on.”

He hung back, baffled by the sudden switch in her.

“Come on, Nathan. You’re right. She needs our support at least.”

Mother Smith had already lit into the group by the time they arrived. Even the defiant ones had dropped their eyes now and stared at the wet deck.

“We call ourselves Saints,” she said, “and we profess to have left the world and all that we possessed for the purpose of better serving our God. Will you, at the very onset, subject the cause of Christ to ridicule by your unwise and improper conduct?”

She waited for an answer. No one spoke or moved.

“You profess to put your trust in God. Then how can you feel to complain and murmur as you do?”

Lydia felt guilt touch her heart, and she too found herself not able to meet those piercing blue eyes that were sweeping the group.

The voice raised a notch in pitch. “You are even more unreasonable than the children of Israel. Here are you sisters, pining away for your rocking chairs. And here are you brethren, grumbling that you shall starve to death before journey’s end. How can that be? Have I not set food before you every day, and made you, who have not provided for your own, as welcome as my own children at my table?

“Where is your faith? Where is your confidence in God? Do you not realize that all things were made by him and that he rules over the works of his own hands?”

She stopped for breath. It was as though the stillness of a cathedral had settled over the group. Even the crowd on the dock who had been standing by watching “the Mormons” had fallen absolutely quiet.

Mother Smith scanned their faces, one by one. “Suppose,” she began again, this time her voice barely above a whisper, “suppose that all of us here, all of us who call ourselves Saints, should lift our hearts in prayer to God that the way might be opened for us. Do you not think that he could cause this wall of ice to part so that we, in no more than a moment, could continue our journey?”

Just then a man from the shore cried out. “Is the Book of Mormon true?”

Mother Smith swung around. “That book was brought forth by the power of God, and it was translated by the gift of the Holy Ghost. Would that I had the voice that could sound as loud as the trumpet of Michael, the Archangel! I would declare the truth of that book from land to land, and from sea to sea, and the family of Adam would be left without excuse.” She smiled briefly, with a little twinkle of humor in her eyes. “Including you, sir.”

The crowd chuckled as the man began to squirm. Slowly Mother Smith turned back to the company. “Now, brethren and sisters,” she pronounced, “if you will, all of you, raise your desires to heaven, that the ice may be broken up, and we be set at liberty, as sure as the Lord lives, it will be done.”

There was a moment of silence, as electric as that moment in a thunderstorm before the blast of lightning splits the night. Lydia knew not what was in the hearts of the others, but she knew what was in hers. O God. It was a cry from the uttermost depths.

Forgive me. Forgive my murmuring cries. Forgive my quickness to turn my face from thee.

There was a brief pause, as though her spirit took a deep breath. Then,

I ask not for myself. I ask only for the child, this precious life that you have seen fit to send to us. If it be thy will, may our journey continue, so that this son of thine can be born safely in Ohio with the rest of thy people Israel.

There was a thunderous crack. She felt the ship shudder beneath her feet, and heard the buildings lining the wharf rattle. She jerked around so hard that the baby lurched within her, jabbing her sharply with pain. For a moment, she could only stare, not comprehending. The sound had come from the harbor’s mouth. For a moment there was nothing to see, just the mass of ice blocking their way. Above and behind her she heard the captain shouting. “Every man to his post! To your posts!”

Then to everyone’s utter amazement, the ice jam began to crack. A seam of dark water began to open, piercing first the base, then the wall of ice. It was as if hell itself were being pried open to make way for them.

“Full steam ahead!” The captain’s voice was a hoarse scream.

The smoke stacks belched black smoke, and the two side paddle wheels groaned and rattled as they started to turn.

“You people down there!” The captain, his face a mottled red, was bellowing at them. “Find a place and hang on. We’re going through!”

People on the docks were screaming and pointing. The path of dark water was widening by the second.

“Come on, Lydia,” Nathan shouted in her ear.

As they raced back to their place on the deck they passed the starboard paddle wheel. It was picking up speed quickly now, churning the water into a foaming cauldron. The front end of the boat was swinging around, turning into the channel that opened before them, a channel that was still widening even as they watched. The crack in the wall had now split enough that they could see through to open water. The ice was shrieking and groaning like a wounded animal.

The captain shouted again from above them. “It’s going to be close.”

Nathan made Lydia lie down on their makeshift bed, and he threw a blanket over her shoulders. “Hang on, Lydia!”

She grabbed at the handle of their valise, but her hand froze in midair. She was staring forward at the wall of ice now looming toward them with increasing speed. She screamed, “We’re going to hit it, Nathan!” She buried her head, grabbing for Nathan’s arm.

Vaguely she was aware of the screams of other passengers, the shouts of the crew. Then there was a tremendous crash just behind her. She whirled around, her eyes flying open. One of the buckets of the starboard paddle wheel had smashed into a jagged shard of ice thicker than an ox’s withers. First one bucket, then another shattered into a thousand splinters.

“We’re through! We’re through!” She wasn’t sure who had shouted it. Maybe her. But Nathan was on his feet pointing back toward the rear of the boat. He leaned down and grabbed her arm and pulled her up. The wake of the boat led in a straight line from the gap through which they had just plunged. In awe they stared as that twenty-foot high floating wall began to move again, like two massive gates being closed. Again the air was rent with the deafening sound of great masses being thrust together. Even as they watched, the narrow opening closed again, shutting in the harbor, trapping the other boats, leaving the Colesville and Thomas B. Marsh groups to wait for another day.

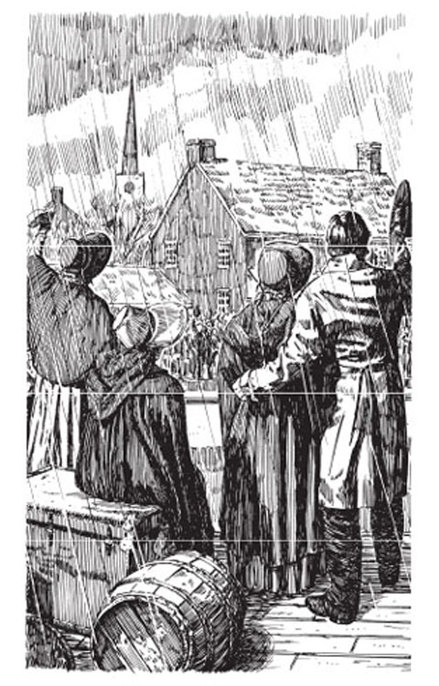

Leaving Buffalo Harbor

Chapter Twelve

Isaac Morley, a young emigrant from Massachusetts, had arrived in Kirtland not long after the first cabin had been built in 1811. He cleared enough land for a small cabin of his own and then returned to New England for Lucy Gunn, his childhood sweetheart.

In many ways Isaac Morley and his wife had been a typical frontier family, except for the fact that they had been even more industrious than most. The first one-room cabin had long since given way to a spacious frame house. There were fields of corn, along with barley and wheat. They made their own molasses and vinegar, kept hives of bees and sold the honey, produced peppermint oil, made lye from ashes for soap. Early on, Isaac had planted several dozen maple trees so they could tap their own syrup. Now called “Morley’s Grove,” the maple trees were in full leaf now in late May, shimmering a brilliant green behind the house.

In addition to bearing nine children and raising seven of them, Lucy grew a patch of flax and raised sheep. The linen and woolen clothes she made not only outfitted her family but also was sold in the village. Isaac was also a skilled cooper and, besides meeting his own needs, sold the barrels, tubs, buckets, and other items in town. It was not surprising that he had been appointed one of three trustees when local government was first instituted in Kirtland. He was quiet and gentle, kind by disposition, but he commanded respect from everyone who knew him.

When missionaries to the Lamanites had arrived in Kirtland late last fall, Isaac and Lucy Morley, two followers of Sidney Rigdon, were among the first to be baptized into the Church. When Joseph Smith arrived in early February with the news that Ohio was to be the new gathering site for the Saints, Father and Mother Morley, as they were known to most of the residents, offered part of their farm as a place for the newcomers. And so it was to the Morley farm that Lucy Mack Smith and the group from New York came after their arrival in Fairport Harbor. That had been almost a week ago. Now the group faced the tasks of building homes in which the newcomers would live.

On this clear May morning Nathan stood in the midst of about twenty acres of timber felled by the hands of professional slashers two or three years previously. The air was still, and smoke from more than two dozen small fires hung in thick layers, stirred only by the movement of the men who moved back and forth tending the fires. The smoke was thick in places and dug at Nathan’s eyes and filled his lungs, making him want to breathe as shallowly as possible.

He and Father Morley and about nine or ten other men were getting the logs ready for use in building cabins, barns, sheds, and rail fencing. They were using a process called “niggering.” Instead of using axes and wedges to cut the logs into the needed lengths—an enormous effort, considering the number of houses being built—they would build small fires at each place where the trunks needed to be cut. One man could tend several fires, and after two or three hours of slow burning, one good whack with an ax would finish the job.

Nathan had never cleared ground this way. They had always worked it through in what his father called “the grunt and swing” method, man and ax against the forest. The idea of slashing particularly fascinated him. Father Morley claimed it had taken no more than three days for the two slashers to level the plot they now worked. That was astounding, since normally two men could work for three weeks or more to clear a heavily timbered acre. When Nathan showed interest, Father Morley explained how they worked.

They would come in and study the lay of the land and the prevailing winds carefully. Then, moving in strips thirty or forty feet wide, they would begin notching the trees on the side that faced the center of the strip, making the notches deeper and deeper as they moved windward. Once the strip was finished, the slashers would wait for the winds to come. When they did, they would leap into action. Moving swiftly to the tree previously picked as the “starter,” they would deliver a few final ax blows to the trunk, already deeply notched. Then, as the wind rose and began to catch the topmost branches with its power, the tree would begin to sway a little. When the wind got high enough, nature took over. There would be a shattering crack and the starter tree would snap off and crash headlong into its nearest neighbors, sending them in turn hurtling against the next ones. Like some gigantic game of dominoes, in a matter of three or four minutes, twenty or thirty acres could be leveled.

The trees were then trimmed and the branches burned, then the logs left to dry and season for three years. Father Morley’s decision to clear an additional twenty acres three years ago had proven to be perfect timing, and the new families had a rich harvest of lumber from which to draw.