The Wolf's Gold (52 page)

‘His decision?’ Felicia laughed out loud, a sound Marcus quickly decided he could do with hearing more. ‘The way I heard it, she told him that given they’re never having intimate relations again as long as she lives, marriage would be both superfluous and a waste of money.’

Marcus raised an eyebrow at his wife, whose cart had arrived in the Alburnus Major camp only an hour before.

‘So she’s not taking to pregnancy that well then?’

Felicia smiled at him, happy to see Appius clinging to the neck of his father’s tunic and working his gums vigorously on a heavy gold pendant that hung around her husband’s neck.

‘Vomiting every morning, bilious for the rest of the day, and overcome with an inexplicable desire to eat raw onion. And if that’s how she is after three months, then life’s certainly going to be interesting for your colleague for the next six. What’s that the baby’s chewing on?’

Marcus looked down.

‘It belonged to Carius Sigilis. I took it from his body out on the lake, after that battle on the ice. I promised Tribune Scaurus that I would return it to his father, if I ever get the chance.’

Felicia took the baby from him, gently easing the pendant from between his jaws.

‘He likes the cold metal on his gums, I suppose. Watch out, by the way, he doesn’t have any teeth yet but he can still nip hard enough to raise a bruise.’ She looked at her husband with a gently raised eyebrow. ‘Another dead friend, Marcus? How are you sleeping?’

His reply was unruffled, despite the unnerving accuracy of her question.

‘Well enough, my love.’

Apart from the hour before dawn, when his father still haunted him with demands for retribution, frequently accompanied of late by the ghost of Lucius Carius Sigilis. While the senator simply berated his son to take revenge, the tribune’s ghost was at the same time both silent and yet gorily persistent in his demands, simply scrawling the same words across whatever surface was to hand in the dream’s context, writing with his fingers with the blood that ran from his wounds.

Felicia took his arm, pulling him close so that the baby was sandwiched between them.

‘You do seem happier. Perhaps you just needed a few good fights to get whatever it was that was troubling you off your mind?’

He smiled back at her, musing on the havoc he intended to wreak if he ever got the opportunity to return to the city of his birth. Praetorian Prefect Perennis and the four men known to him only as ‘The Emperor’s Knives’ were enough of a list for the time being, although he was sure that other names would come to light once he started working his way through the first five. His hand tensed on the dagger at his belt, the scarred skin over his knuckles tightening until the marks disappeared into the white flesh.

‘Yes my love. Perhaps I did.’

HISTORICAL NOTE

As a historical people the Sarmatians are easily the equal of the Romans, with whom they interacted and frequently fought. Entering known history in the seventh century

BC

, they occupied the land to the east of the Don River and south of the Ural Mountains. Having lived in peace with their western neighbours the Scythians for several centuries, it was in the third century

BC

that this pattern abruptly changed. The Sarmatian tribes came across the Don and took on the Scythians, driving them off their pastures and establishing a new reign over this fertile land that was to last for centuries.

A nomadic people who largely lived off their herds, the several Sarmatian tribes – Roxolani, Iazyge, Aorsi, Siraces and Sauromatae – were tent dwellers whose young women, trained to fight alongside the men, are thought to have given rise to the legend of the Amazons. Hippocrates described how female Sarmatian babies were deliberately mutilated by the cauterisation of the right nipple, to inhibit growth of the breast so as to make the resulting adult female’s right arm as strong as possible. The bulk of the Sarmatian forces tended to be light cavalry armed predominantly with bows, but just as the main battle tank tends to get most of the media attention on the modern battlefield, it was the more heavily armoured lancer, named by the Romans as the

contarius

for the three- to four-metre-long

contus

lance with which the rider was armed, that was the focus for the writers of the age. Manoeuvring in massed squadrons, Sarmatian heavy cavalry used the classic tactics of mounted shock to overcome their enemies, tactics which could only be matched by either superbly disciplined and trained heavy infantry, preferably armed with long spears and sheltered behind sharpened wooden stakes, or by highly mobile horse archers who could outpace their charge whilst peppering them with heavy-headed armour-piercing arrows.

By the first century

AD

the Iazyge were frequently engaging with the Roman Empire in the form of regular border incursions, often crossing the Danube in winter when the river’s ice was sufficiently thick to support the weight of their horses and wagons. As the Sarmatian tribes leapt into the pages of history in a series of devastating attacks on their neighbours the Parthians, the Armenians and the Medians, the Iazyges laid waste to the Roman provinces of Pannonia and Moesia (the provinces that lay on the southern side of the Danube river) as they pushed up the Danube to occupy the Hungarian plain between the Dacian kingdom and Pannonia Inferior. In

AD

92 they provided a portent of the danger that they were to present to the empire for centuries to come, combining with the German Quadi and Marcomanni tribes to destroy an entire Roman legion – Twenty-First Rapax (a name which meant ‘Predator’ and proved sadly unapt for this last action in their long history). During the same period the Roxolani made repeated raids into Moesia, and came to side with the Dacians in their wars with Rome, while the Iazyge were more closely aligned with the empire as its expansionary impulse led to a series of assaults on the powerful Dacian kingdom. When Dacia was eventually conquered by Trajan, placing a well-defended piece of imperial territory between the two tribes, the Romans astutely allowed them to maintain contact through the province, and paid generous subsidies to ensure peace. Nevertheless, the time was bound to come when this would no longer be sufficient.

So it was that the Iazyges once again joined forces with the German tribes in the Marcomannic wars of the 160s, taking the fight to a disease-weakened Roman army afresh in an alliance that was to last until a seemingly unmatched battle fought out on the frozen Danube. A dazzling Roman victory resulted – I did mention the efficacy of superbly disciplined and trained heavy infantry against the

contarius

– with 8,000 Iazyge horsemen being sent to serve in Britain as the price of failure. The uneasy peace that followed is the context for the fictional events described in

The Wolf’s Gold

, based on Cassius Dio’s report that two future contenders for the throne, Niger and Albinus, were instrumental in dealing with an Iazyge revolt early in Commodus’s reign, ten years after the battle on the Danube. After this heavy defeat the Sarmatians were not to trouble Rome sufficiently for it to enter the surviving historical record for another fifty years, but they continued to harass the empire throughout the third century until increasingly pragmatic imperial policy made a virtue out of a necessity, and allowed several mass Sarmatian resettlements inside the empire’s frontiers as a means of building a bulwark against the encroaching Goths. By the time of the

Notitia Dignitatum

(a documentary ‘snapshot’ of the Roman state’s geography and organisation at the end of the fourth century), Sarmatian settlement throughout the northern empire was apparently commonplace, and Sarmatians rose to positions of power and influence as the western empire began to succumb to the pressures building upon its borders from the east. But that, as more than one of my historical fiction colleagues would tell you, is another story altogether.

One last (but important) point. As the regular reader will know, I present my stories against the background of documented history and set them in the authentic context of the empire’s topography as much as is possible. When it comes to the names of the places I use, I do try to present an understandable version of the Latin place name wherever possible – where it can be translated straight into English and make sense. Hence – my usual example – Brocolitia on Hadrian’s Wall becomes the wonderfully evocative Badger Holes. This isn’t always possible, of course, since the Romans were great adopters of other people’s ideas, weapons, tactics and yes, place names. Alburnus Major, Apulum, Porolissum and Napoca are all good examples of this, with their roots believed to lie in the names given to them by the tribes that founded the original settlements on which the Romans built their cities and fortresses. Just as the conquerors knew that allowing the locals to worship their own gods made for a happier subject population (as long as they recognised the emperor as the supreme deity), so it made sense to use the place name that was already in common usage. With this in mind, and where prudent to do so, I have stayed on the safe side and retained the Roman name by which we know these fortress settlements. On the other hand, where Roman forts are known to have existed but whose original names are unknown, I have felt free to come up with my own name for what would otherwise be an anonymous fort, and something of a blot on the narrative. As ever, in the event that my research is proven to be at fault, I will be eternally grateful for any clarification that any reader can offer.

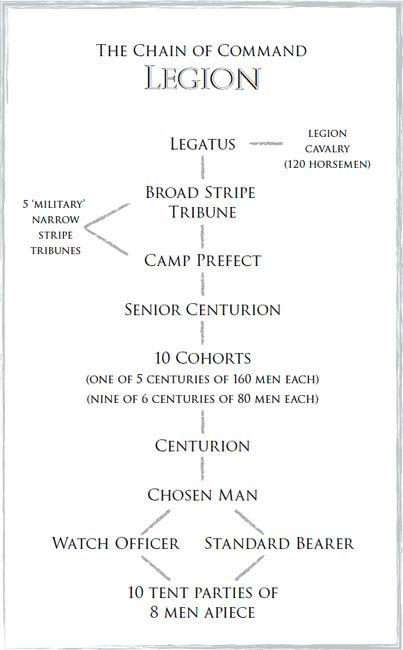

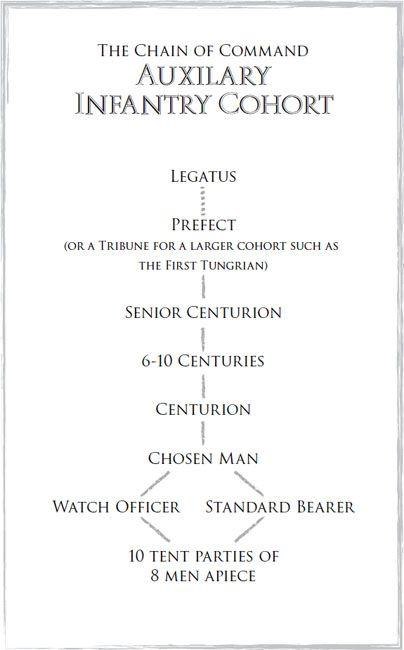

THE ROMAN ARMY IN 182 AD

By the late second century, the point at which the

Empire

series begins, the Imperial Roman Army had long since evolved into a stable organization with a stable

modus operandi

. Thirty or so

legions

(there’s still some debate about the 9th Legion’s fate), each with an official strength of 5,500 legionaries, formed the army’s 165,000-man heavy infantry backbone, while 360 or so

auxiliary

cohorts

(each of them the equivalent of a 600-man infantry battalion) provided another 217,000 soldiers for the empire’s defence.

Positioned mainly in the empire’s border provinces, these forces performed two main tasks. Whilst ostensibly providing a strong means of defence against external attack, their role was just as much about maintaining Roman rule in the most challenging of the empire’s subject territories. It was no coincidence that the troublesome provinces of Britain and Dacia were deemed to require 60 and 44 auxiliary cohorts respectively, almost a quarter of the total available. It should be noted, however, that whilst their overall strategic task was the same, the terms under the two halves of the army served were quite different.

The legions, the primary Roman military unit for conducting warfare at the operational or theatre level, had been in existence since early in the Republic, hundreds of years before. They were composed mainly of close-order heavy infantry, well-drilled and highly motivated, recruited on a professional basis and, critically to an understanding of their place in Roman society, manned by soldiers who were Roman citizens. The jobless poor were thus provided with a route to both citizenship and a valuable trade, since service with the legions was as much about construction – fortresses, roads, and even major defensive works such as Hadrian’s Wall – as destruction. Vitally for the maintenance of the empire’s borders, this attractiveness of service made a large standing field army a possibility, and allowed for both the control and defence of the conquered territories.

By this point in Britannia’s history three legions were positioned to control the restive peoples both beyond and behind the province’s borders. These were the 2nd, based in South Wales, the 20th, watching North Wales, and the 6th, positioned to the east of the Pennine range and ready to respond to any trouble on the northern frontier. Each of these legions was commanded by a

legatus

, an experienced man of senatorial rank deemed worthy of the responsibility and appointed by the emperor. The command structure beneath the legatus was a delicate balance, combining the requirement for training and advancing Rome’s young aristocrats for their future roles with the necessity for the legion to be led into battle by experienced and hardened officers.