The Wolf and the Lamb

Read The Wolf and the Lamb Online

Authors: Frederick Ramsay

| The Wolf and the Lamb |

| Number IV of Jerusalem Mystery |

| Frederick Ramsay |

| Poisoned Pen Press (2014) |

It’s Passover. Gamaliel, and his physician friend, Loukas, are crime-solving a third time - reluctantly. Pontius Pilate has been accused of murder. He denies the crime. If convicted, he might escape death but would be removed from Judea. Those rejoicing urge the Rabban to mind his own business. But Gamaliel is a Just Man which is, as Pilate points out, “your weakness and also your strength.”

Knowing that exonerating the Roman could cost him his position, possibly his life, Gamaliel, as would Sherlock Holmes centuries later, examines evidence and sorts through tangled threads, teasing out suspects who include assassins, Roman nobles, Pilate’s wife, rogue legionnaires, slaves, servants, thespians, and a race horse named Pegasus. Unusually, justice triumphs over enmity. Gamaliel is satisfied, High Priest Caiphas is irate, Loukas accepts an apprentice from Tarsus, and few notice the events of what will later be known as Easter.

Ramsay’s plausible narrative answers some questions which have puzzled Biblical scholars for centuries. Why did Pilate hear the case against Jesus? Why invent a tradition that required one prisoner be released at Passover? Having done so, why offer the most terrifying criminal in the country, Barabbas, as the substitute for Jesus when two better, less dangerous prisoners were at hand? And we ask, why could Caiphas not heed Gamaliel’s warnings not to martyr the man?

Copyright © 2014 by Frederick Ramsay

First E-book Edition 2014

ISBN: 978146420 3299 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

Contents

Dedication

To The Rt. Rev. Robert Wilkes Ihloff,

Bishop of the Diocese of Maryland (Retired) and erstwhile Rabban

First, the usual and necessary thank you to the folks at the Poisoned Pen Press who make all this happen for me and for you. In an age of e-books and instant authorship, it is easy to forget that publishing is more than just a business. It combines art and craft in ways that are not often understood or appreciated. Readers sometimes forget that for a publisher to put a book into their hands involves more than checking for spelling, comma placement, and digitalizing. Book publishers must also judge whether you will like a particular piece and will buy it, whether the story needs to be told and, indeed, if either of those things even matter for a particular book. Sometimes a book will be released just because it is something that needs doing. Anyway, this is number sixteen for the Press and for me, and I want to make sure you know and they know how happy that makes me (and I hope you, too).

Second, I want to thank all those people who, over nearly eight decades, stuffed my head with the facts, speculation, history, and outright lies, all of which is the primary source of what passes for what I call research. I could not write about Jerusalem in the First Century without them.

Finally, to all of the folks—especially my patient wife, Susan—who have supported me in this giddy late-in-life career as a storyteller, many thanks.

Frederick Ramsay

2014

For those readers who have already experienced Gamaliel and his investigative skills in

The Eighth Veil

and

Holy Smoke,

the notes carried here and in the Appendix at the end of the book may be repetitious. For new readers, I hope they help clarify some of the complexities of life in Jerusalem during the early part of the first century. I urge readers to slip a paper clip back there somewhere for quick reference.

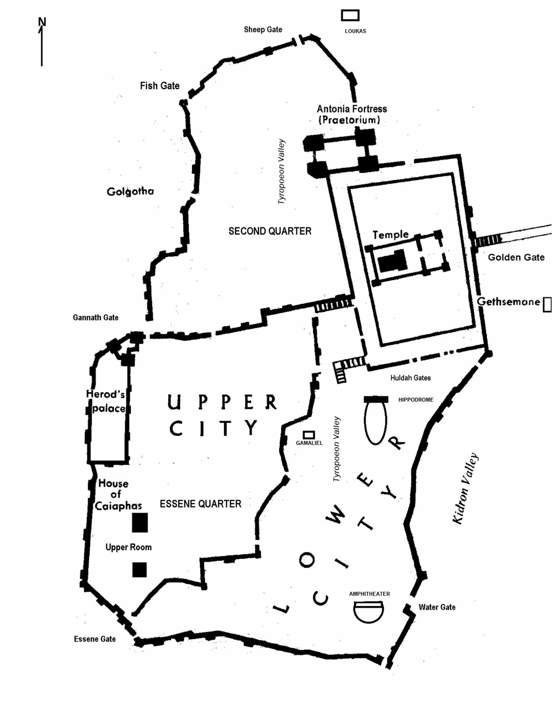

Another note is in order for those who are reading this series in sequence; I have had to alter the map of the city. Gamaliel’s house has been shifted slightly to the west to make room for the hippodrome. (Yes, there was one in Jerusalem at the time. It was not as large as that depicted in

Ben Hur

, but it did exist.) The Antonia Fortress and its controversial placement is discussed in more detail in the Appendix.

Days of the Week

Yom Rishon = first day = Sunday (starting at preceding sunset)

Yom Sheni = second day = Monday

Yom Shlishi = third day = Tuesday

Yom Revi’i = fourth day = Wednesday

Yom Chamishi = fifth day = Thursday

Yom Shishi = sixth day = Friday

Yom Shabbat = Sabbath, seventh day (Rest day) = Saturday

Chronology

Given the number of events that had to take place, this author believes it unlikely the narrative as presented in the Synoptic Gospels could have occurred as written. If, however the Last Supper was celebrated on a Tuesday (Yom Shlishi ) with his Essene friends (their Passover), then, there is time enough for an arrest late at night with a flogging, a hearing before the Sanhedrin, two trips to the Prefect, one to the King, another flogging, and a march through the streets of Jerusalem to Golgotha and a crucifixion by nine in the morning.

With these thoughts in mind, you will find a fuller explanation and resultant chronology in the Appendix.

The wolf also shall dwell with the lamb,

and the leopard shall lie down with the kid;

and the calf and the young lion and the fatling together;

and a little child shall lead them.

Isaiah 11:6,

King James Version

The Wolf and the Lamb

The Wolf, meeting with a Lamb that had strayed away from the flock, resolved not to resort to violence, but to find some legitimate justification for the Wolf’s right to eat him. He addressed him:

“Young sir, last year you insulted me.”

“Indeed,” bleated the Lamb, “but I was not born yet.”

Then the Wolf said, “You feed in my pasture.”

“No,” replied the Lamb, “I have not yet tasted grass.”

Again said the Wolf, “Well, you drink from my well.”

“No,” pleaded the Lamb, “I never drank water yet, for my mother’s milk is both food and drink to me so far.”

Upon which the Wolf seized him and ate him anyway, saying, “Well! I won’t go without my supper, even though you refute every one of my imputations.”

Moral: The tyrant will always find a pretext for his tyranny.

He couldn’t remember venturing this deep into the labyrinthine corridors and arbitrary passages of the Antonia Fortress. He’d never needed to. He took one tentative step forward and paused, put out his hand and felt the stone wall—damp. He inhaled acrid smoke, burning pitch from the torches. Why had Priscus asked him to meet in this dank and dreary hallway? Located as it was deep in the bowels of the building—the

cloaca

, he would have said—Priscus must have had a great need for secrecy—routine in Roman politics. Half the torches were dark and those that still glowed sent tendrils of smoke to the ceiling. Had they been extinguished recently? If so, by whom and why? Lighted or dark, they lined either side of the corridor and projected from sconces at angles as if to salute any passerby. He hesitated and peered into the darkness. Like one of his hunting dogs when it caught the scent of a stag in flight, he went into full alert, unmoving and listening. If he had shared the dog’s cropped ears, they would have been twitching this way and that. The only sound he heard was the beating of his own heart.

He strained to see into the hallway’s depths. It was impossible to determine where it led or how long it might be. It could as easily disappear into an abyss as come to an abrupt halt a few cubits farther along. Then, it might end at an intersecting wall or continue for a half mile and out into the night air beyond the city walls to the north. He knew the last wasn’t the case, but this inky hallway with half its torches unlit created that illusion. Perhaps the fort’s builder, the first Herod, in assembling this monument to the late and, for most, unlamented Mark Antony, thought a siege inevitable or that Antony would retreat from Egypt to Judea with his Ptolemaic Queen to make his stand against Octavian. Or perhaps it was simply another manifestation of that King’s diseased and suspicious mind. Throughout the year the space housed a resident contingent of legionnaires with a Centurion in command. It could have served as well if half or a quarter its current size.

Priscus’ message made it clear he wanted to meet at this place, that he had something important to tell him, and that it required privacy. The message had been vague and the legionnaire who bore it nearly inarticulate, but he’d no reason to suspect anything out of the ordinary so he’d come as asked. Priscus, after all, was a loyal member of his entourage and a serving officer. On the other hand, he knew that all Roman politics operated on intrigue and duplicity. He shuddered. He didn’t know why. It wasn’t as if he were afraid.

He took another tentative step forward and reached up to free one of the lighted torches from its bracket. He held it aloft squinting into the darkness, straining to make out what lay further on. He touched its flame to the still-smoking pitch-soaked fabric at the end of a nearby staff. It burst into flame and a bit of his anxiety waned as the light penetrated deeper into the gloom. He lit another and moved on. As he leaned forward to light a third, he stumbled against a form lying at his feet. Startled, he jerked his foot back. He looked again and recoiled at the sight of a corpse. He took a deep breath, knelt, and rolled the body over.

A dagger had been thrust in the man’s chest. Its gilded and stone-studded hilt protruded from his bloody short toga. The knife’s angle was all wrong. He lifted the torch to cast light on the dead man’s face. Aurelius Decimus’ lifeless eyes stared at the ceiling, the expression of shock at his unexpected demise still frozen on his face. None of this made any sense. He dismissed the notion that Aurelius Decimus had committed suicide. No one with that man’s enormous ambition would consider such an action. Furthermore, to fall on one’s dagger or sword took a measure of courage that he knew this man did not possess. Not suicide. That meant that someone had stabbed him, murdered him. It seemed so unlikely. A man murdered in the depths of the Antonia Fortress, the very symbol of Roman preeminence and a safe haven for its citizens. Yet, here the ambitious Aurelius lay in an expanding pool of blood.

He regained his feet and glanced around, uncertain what to do next. And what had happened to Priscus? Footsteps scraped against the stones behind him—several pairs, in fact. He stood and faced about.

“Priscus? Is that you? Come here.”

“Pontius Pilate, Emperor’s Prefect of Judea and Overseer of the Palestine,

tu deprenditur discurrent caede.

”

“I am to be arrested for murder? I only this moment arrived and found this man lying here. I did not murder anyone, Cassia.”

“Yet our friend Aurelius Decimus lies dead at your feet, Prefect. The dagger in his chest is yours, I believe.”

Was it? It was.

“And I can see no reasonable explanation for your presence in this remote part of the Fortress other than an assignation with him in order to remove the one man who could have sent you back to Rome in disgrace.”

“My dagger? Sent back? Cassia, what am I being accused of?”

“Assassination, Prefect, as you well know.

Sicarius.

”