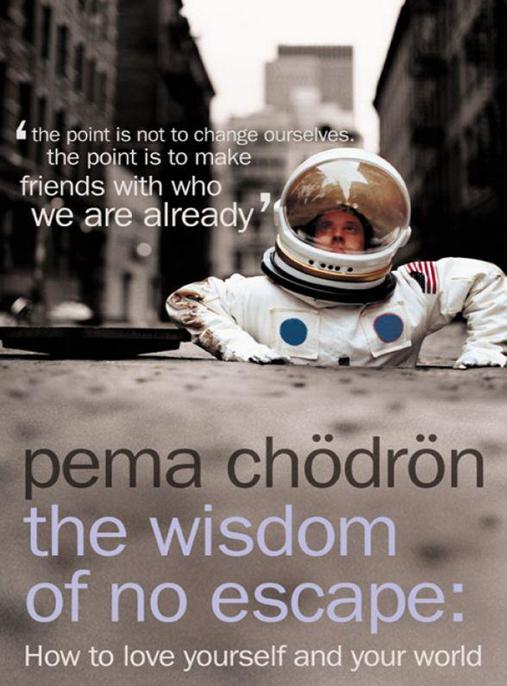

The Wisdom of No Escape: How to Love Yourself and Your World

Read The Wisdom of No Escape: How to Love Yourself and Your World Online

Authors: Pema Chödrön

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism, #Meditation

the wisdom

of no escape

how to love yourself

and your world

pema chödrön

To my teacher, Vidyadhara the Venerable Chögyam Trungpa, Rinpoche, and to my children, Arlyn and Edward

contents

cover

title page

dedication

preface

3. finding our own true nature

4. precision, gentleness, and letting go

7. taking a bigger perspective

8. no such thing as a true story

9. weather and the four noble truths

10. not too tight, not too loose

14. not preferring samsara or nirvana

15. the dharma that is taught and the dharma that is experienced

bibliography

about the author

resources

copyright

about the publisher

T

he talks in this book were given during a one-month practice period

(dathun)

in the spring of 1989. During that month the participants, both lay and monastic, used the meditation technique presented by Chögyam Trungpa that is described in this book. The formal sitting meditation was balanced by walking meditation and eating meditation

(oryoki)

and by maintaining the environment of the monastery and helping to prepare the meals.

Early each morning these talks were presented. They were intended to inspire and encourage the participants to remain wholeheartedly awake to everything that occurred and to use the abundant material of daily life as their primary teacher and guide.

The natural beauty of Gampo Abbey, a Buddhist monastery for Western men and women founded in 1983 by Chögyam Trungpa, was an important element in the talks. The abbey is located on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, at the end of a long dirt road, on cliffs high above the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, where the wildness and playfulness of the weather,

the animals, and the landscape permeate the atmosphere. As one sits in the meditation hall, the vastness of the sky and water permeates the mind and heart. The silence of the place, intensified by the sounds of sea and wind, birds and animals, permeates the senses.

During the dathun (as always at the abbey), the participants kept the five monastic vows: not to lie, not to steal, not to engage in sexual activity, not to take life, and not to use alcohol or drugs. The resulting collaboration of nature, solitude, meditation, and vows made an alternatingly painful and delightful ‘no exit’ situation. With nowhere to hide, one could more easily hear the teachings given in these simple talks in a wholehearted, open-minded way.

The message for the dathun as well as for the reader is to be with oneself without embarrassment or harshness. This is instruction on how to love oneself and one’s world. It is therefore simple, accessible instruction on how to alleviate human misery at a personal and global level.

I wish to thank Ane Trime Lhamo; Jonathan Green of Shambhala Publications, who encouraged me to publish a book; Migme Chödrön of Gampo Abbey, who transcribed and edited the talks; and Emily Hilburn Sell of Shambhala Publications, who shaped them into their present form. Whatever is said here is but my very limited understanding, thus far, of what my teacher, Chögyam Trungpa, Rinpoche,

compassionately and with great patience showed to me.

May it be of benefit.

T

here’s a common misunderstanding among all the human beings who have ever been born on the earth that the best way to live is to try to avoid pain and just try to get comfortable. You can see this even in insects and animals and birds. All of us are the same.

A much more interesting, kind, adventurous, and joyful approach to life is to begin to develop our curiosity, not caring whether the object of our inquisitiveness is bitter or sweet. To lead a life that goes beyond pettiness and prejudice and always wanting to make sure that everything turns out on our own terms, to lead a more passionate, full, and delightful life than that, we must realize that we can endure a lot of pain and pleasure for the sake of finding out who we are and what this world is, how we tick and how our world ticks, how the whole thing just

is.

If we’re committed to comfort at any cost, as soon as we come up against the least edge of pain, we’re going to run; we’ll never know what’s beyond that particular barrier or wall or fearful thing.

When people start to meditate or to work with

any kind of spiritual discipline, they often think that somehow they’re going to improve, which is a sort of subtle aggression against who they really are. It’s a bit like saying, ‘If I jog, I’ll be a much better person.’ ‘If I could only get a nicer house, I’d be a better person.’ ‘If I could meditate and calm down, I’d be a better person.’ Or the scenario may be that they find fault with others; they might say, ‘If it weren’t for my husband, I’d have a perfect marriage.’ ‘If it weren’t for the fact that my boss and I can’t get on, my job would be just great.’ And ‘If it weren’t for my mind, my meditation would be excellent.’

But loving-kindness –

maitri

– toward ourselves doesn’t mean getting rid of anything, Maitri means that we can still be crazy after all these years. We can still be angry after all these years. We can still be timid or jealous or full of feelings of unworthiness. The point is not to try to change ourselves. Meditation practice isn’t about trying to throw ourselves away and become something better. It’s about befriending who we are already. The ground of practice is you or me or whoever we are right now, just as we are. That’s the ground, that’s what we study, that’s what we come to know with tremendous curiosity and interest.

Sometimes among Buddhists the word

ego

is used in a derogatory sense, with a different connotation than the Freudian term. As Buddhists, we might say, ‘My ego causes me so many problems.’ Then we might think, ‘Well, then, we’re supposed to get rid of

it, right? Then there’d be no problem.’ On the contrary, the idea isn’t to get rid of ego but actually to begin to take an interest in ourselves, to investigate and be inquisitive about ourselves.

The path of meditation and the path of our lives altogether has to do with curiosity, inquisitiveness. The ground is ourselves; we’re here to study ourselves and to get to know ourselves now, not later. People often say to me, ‘I wanted to come and have an interview with you, I wanted to write you a letter, I wanted to call you on the phone, but I wanted to wait until I was more together.’ And I think, ‘Well, if you’re anything like me, you could wait forever!’ So come as you are. The magic is being willing to open to that, being willing to be fully awake to that. One of the main discoveries of meditation is seeing how we continually run away from the present moment, how we avoid being here just as we are. That’s not considered to be a problem; the point is to see it.

Inquisitiveness or curiosity involves being gentle, precise, and open – actually being able to let go and open. Gentleness is a sense of goodheartedness toward ourselves. Precision is being able to see very clearly, not being afraid to see what’s really there, just as a scientist is not afraid to look into the microscope. Openness is being able to let go and to open.

The effect of this month of meditation that we are beginning will be as if, at the end of each day, someone were to play a video of you back to yourself and you could see it all. You would wince quite often

and say ‘Ugh!’ You probably would see that you do all those things for which you criticize all those people you don’t like in your life, all those people that you judge. Basically, making friends with yourself is making friends with all those people too, because when you come to have this kind of honesty, gentleness, and goodheartedness, combined with clarity about yourself, there’s no obstacle to feeling loving-kindness for others as well.

So the ground of maitri is ourselves. We’re here to get to know and study ourselves. The path, the way to do that, our main vehicle, is going to be meditation, and some sense of general wakefulness. Our inquisitiveness will not be limited just to sitting here; as we walk through the halls, use the lavatories, walk outdoors, prepare food in the kitchen, or talk to our friends – whatever we do – we will try to maintain that sense of aliveness, openness, and curiosity about what’s happening. Perhaps we will experience what is traditionally described as the fruition of maitri – playfulness.

So hopefully we’ll have a good month here, getting to know ourselves and becoming more playful, rather than more grim.

I

t’s very helpful to realize that being here, sitting in meditation, doing simple everyday things like working, walking outside, talking with people, bathing, using the toilet, and eating, is actually all that we need to be fully awake, fully alive, fully human. It’s also helpful to realize that this body that we have, this very body that’s sitting here right now on this shrine room floor, this very body that perhaps aches because it’s only day two of the dathun, and this mind that we have at this very moment, are exactly what we need to be fully human, fully awake, and fully alive. Furthermore, the emotions that we have right now, the negativity and the positivity, are what we actually need. It is just as if we had looked around to find out what would be the greatest wealth that we could possibly possess in order to lead a decent, good, completely fulfilling, energetic, inspired life, and found it all right here.

Being satisfied with what we already have is a magical golden key to being alive in a full, unrestricted, and inspired way. One of the major obstacles to what is traditionally called enlightenment is

resentment, feeling cheated, holding a grudge about who you are, where you are, what you are. This is why we talk so much about making friends with ourselves, because, for some reason or other, we don’t feel that kind of satisfaction in a full and complete way. Meditation is a process of lightening up, of trusting the basic goodness of what we have and who we are, and of realizing that any wisdom that exists, exists in what we already have. Our wisdom is all mixed up with what we call our neurosis. Our brilliance, our juiciness, our spiciness, is all mixed up with our craziness and our confusion, and therefore it doesn’t do any good to try to get rid of our so-called negative aspects, because in that process we also get rid of our basic wonderfulness. We can lead our life so as to become more awake to who we are and what we’re doing rather than trying to improve or change or get rid of who we are or what we’re doing. The key is to wake up, to become more alert, more inquisitive and curious about ourselves.