The Winter Ghosts (2 page)

Authors: Kate Mosse

‘

Bones and shadows and dust. I am the last. The others have slipped away into darkness. Around me now, at the end of my days, only an echo in the still air of the memory of those who once I loved. Solitude, silence. Peyre sant . . .

’

Bones and shadows and dust. I am the last. The others have slipped away into darkness. Around me now, at the end of my days, only an echo in the still air of the memory of those who once I loved. Solitude, silence. Peyre sant . . .

’

Saurat stopped and stared now with interest at the reserved Englishman standing before him. He did not look like a collector, but then one never could tell.

He cleared his throat. ‘May I ask where you came by this, Monsieur . . . ?’

‘Watson.’ Freddie took his card from his pocket and laid it with a snap on the counter between them. ‘Frederick Watson.’

‘You are aware this is a document of some historical significance?’

‘To me its significance is purely personal.’

‘That may be, but nevertheless . . .’ Saurat shrugged. ‘It is something that has been in your family for some time?’

Freddie hesitated. ‘Is there a place we could talk?’

‘Of course.’ Saurat gestured to a low card table and four leather armchairs set in an alcove at the rear of the shop. ‘Please.’

Freddie took the letter and sat down, watching as Saurat stooped beneath the counter again, this time producing two thick glass tumblers and a bottle of mellow, golden brandy. He was unusually graceful, delicate even, Freddie thought, for such a large man. Saurat poured them both a generous measure, then lowered himself into the chair opposite. The leather sighed beneath his weight.

‘So, will you translate it for me?’

‘Of course. But I am still intrigued to know how you come to be in possession of such a document.’

‘It’s a long story.’

Another shrug. ‘I have the time.’

Freddie leaned forward and slowly fanned his long fingers across the surface of the table, making patterns on the green baize.

‘Tell me, Saurat, do you believe in ghosts?’

A smile stole across the other man’s lips.

‘I am listening.’

Freddie breathed out, with relief or some other emotion, it was hard to tell.

‘Well then,’ he said, settling back in his chair. ‘The story begins almost five years ago, not so very far from here.’

ARIÈGE

December 1928

It was a dirty night in late November, a few days shy of my twenty-seventh birthday, when I boarded the boat train for Calais.

I had no ties to keep me in England, and my health in those days was poor. I’d spent some time in a sanatorium and, since then, had struggled to find a vocation, a calling in life. A stint as a junior assistant in an ecclesiastical architect’s office, a month as a commission agent; nothing had stuck. I was not suited to work nor it, apparently, to me. After a particularly vicious bout of influenza, my doctor suggested a tour of the castles and ruins of the Ariège would do my shattered nerves some good. The clean air of the mountains might restore me, he said, where all else had failed.

So I set off, with no particular route in mind. I was no more lonely motoring on the Continent than I had been in England, surrounded by acquaintances and my few remaining friends who didn’t understand why I could not forget. A decade had passed since the Armistice. Besides, there was nothing unique to my suffering. Every family had lost someone in the War; fathers and uncles, sons, husbands and brothers. Life moved on.

But not for me. As each green summer slipped into the copper and gold of another autumn, I became less able, not more, to accept my brother’s death. Less willing to believe George was gone. And although I went through all the appropriate emotions - disbelief, denial, anger, regret - grief still held me in its grasp. I despised the wretched creature I had become, but seemed unable to do anything about it. Looking back, I am not certain that, when I stood on the rocking boat watching the white cliffs of Dover growing smaller behind me, I had any intention of returning.

The change of scene did help, though. Once I’d negotiated my way through those northern towns and villages where the scent of battle still hung heavy in the air, I felt less stuck in the past than I had at home. Here in France, I was a stranger. I was not supposed to fit in and nor did anyone expect me to. No one knew me and I knew no one. There was nobody to disappoint. And while I cannot say that I took much pleasure in my surroundings, certainly the day-to-day business of eating and driving and finding a bed occupied my waking hours.

The night, of course, was another matter.

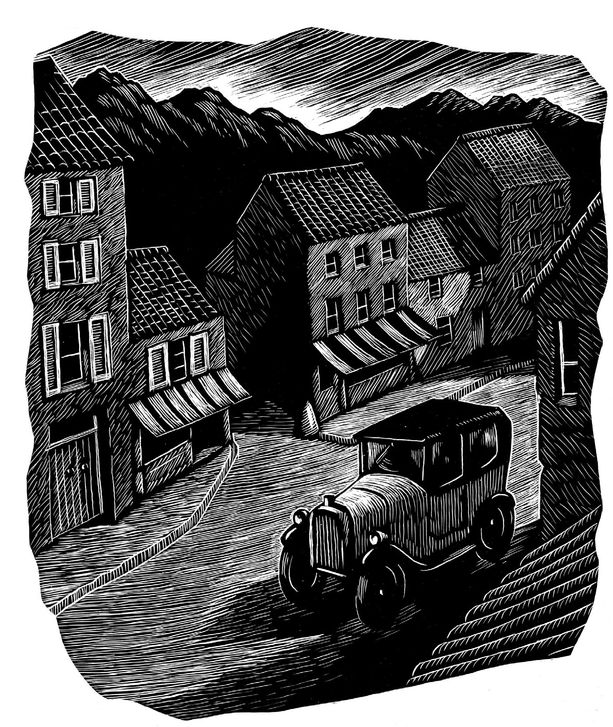

So it was that some few weeks later, on 15 December, I arrived at Tarascon-sur-Ariège in the foothills of the Pyrenees. It was late in the afternoon and I was stiff from rattling over the basic mountain roads. The temperature inside my little box saloon was barely higher than that outside. My breath had caused the windows to steam up, and I was obliged to wipe the condensation from the windscreen with my sleeve.

I entered the small town via the avenue de Foix in the pink light of the fading day. The sun falls early in those high valleys and the shadows on the narrow cobbled streets were already deep. Ahead of me, a thin, eighteenth-century clock tower perched high on a vertiginous outcrop, like a sentinel to welcome home the solitary traveller. Straight away, there was something about the place - a sense of confidence and acceptance of its place in the world - that appealed to me. A suggestion of old values coexisting with the demands of the twentieth century.

Through the gaps between the window and the frame of the car slipped the acrid yet sweet smell of burning wood and resin. I saw flickering lights in little houses, waiters in long black aprons moving between tables in a café, and I ached to be part of that world.

I decided to stop for the night. At the junction with the Pont Vieux, I was obliged suddenly to brake to avoid a man on a bicycle. The beam from his lamp jumped and lurched as he swerved the potholes in the road. While I waited for him to pass, my eye was drawn by the bright light of the

boulangerie

window opposite. As I watched, a young sales assistant, her coarse brown hair escaping from beneath her cap, reached down into the glass cabinet and lifted out a

Jésuite,

or perhaps a cream

éclair

.

boulangerie

window opposite. As I watched, a young sales assistant, her coarse brown hair escaping from beneath her cap, reached down into the glass cabinet and lifted out a

Jésuite,

or perhaps a cream

éclair

.

Much time has passed and memory is an unreliable friend, but, in my mind’s eye, still I see her pause for a moment, then smile shyly at me before placing the

pâtisserie

in the box and tying it with ribbon. The thinnest shaft of light entered the empty chambers of my heart, just for a moment. Then it disappeared, extinguished by the weight of all that had gone before.

pâtisserie

in the box and tying it with ribbon. The thinnest shaft of light entered the empty chambers of my heart, just for a moment. Then it disappeared, extinguished by the weight of all that had gone before.

I found lodgings without difficulty at the Grand Hôtel de la Poste, which advertised a garage for the use of its customers. Although my yellow Austin Seven was the sole occupant, there was a service station, the Garage Fontez, a little further along the street and the sense that things in Tarascon were on the up. This was confirmed as I signed the register. The hotel proprietor told me how an aluminium factory had opened only a few weeks before. It would, he believed, bring prosperity to the district and give the young men a reason to stay.

The precise details of the conversation escape me now. At that time, I’d lost the appetite for casual talk. Over ten years of mourning, my ability to engage with anyone other than George had ebbed away. He walked beside me and was the only person to whom I could unburden myself. I needed no one else.

But on that December afternoon in that little hotel, I saw a glimpse of how other people lived, and regretted I could not learn to do the same. Even now I remember the

patron

’s passion for the project of regeneration, his optimism and ambition for his town. It stood in stark contrast to my own limited horizons. As always at such moments, I felt more of an outsider than ever. I was glad when, having shown me to my lodgings, he left me alone.

patron

’s passion for the project of regeneration, his optimism and ambition for his town. It stood in stark contrast to my own limited horizons. As always at such moments, I felt more of an outsider than ever. I was glad when, having shown me to my lodgings, he left me alone.

The room was on the first floor, overlooking the street, with a pleasant enough outlook. A large window with freshly painted shutters, a single bed with heavy counterpane, a washstand and an armchair. Plain, clean, anonymous. The sheets were cold to the touch. We suited one another, the room and I.

La Tour du Castella

I unpacked, washed the dirt of the road from my face and hands, then sat and looked down on the avenue de Foix as I smoked a cigarette.

I decided to take a turn around the town on foot before dinner. It was still early, but the temperature had fallen, and the cobblers and

pharmacie

, the

boucherie

and the

mercerie

had already turned off their lights and fastened their shutters. A row of dead men’s eyes, seeing nothing, revealing nothing.

pharmacie

, the

boucherie

and the

mercerie

had already turned off their lights and fastened their shutters. A row of dead men’s eyes, seeing nothing, revealing nothing.

I walked along the quai de l’Ariège, back to the stone bridge over the river, at the point where the white waters of the Ariège and the Vicdessos meet. I loitered a while in the dusk, then continued over to the right bank of the river. This, I had been told, was the oldest and most distinctive part of the town, the

quartier

Mazel-Viel.

quartier

Mazel-Viel.

I strolled through a pretty garden, bleak in winter, which perfectly matched my mood. I paused, as I always did, at the memorial raised in honour of those who had fallen on the battlefields of Ypres and Mons and Verdun. Even in Tarascon, far from the theatre of war, there were so many names set down in stone. So very many names.

Just behind the monument, a corridor of gaunt fir and black pine led to the wrought-iron gate of the cemetery. The stone tips of carved angels’ wings, Christian crosses and the peaks of one or two more elaborate tombs were just visible above the high walls. I hesitated, tempted to visit the sleepers in the damp earth, but resisted the impulse. I knew better than to linger among the dead. I started to turn away.

But I was too slow. I saw him. For a fraction of a second, a shadow in the diminishing light or a trick of my unreliable eyes, I saw him standing on the shallow old stone steps directly ahead of me. I felt a jolt of happiness and raised my hand to wave. Like the old days.

‘George?’

Other books

Murder is the Pits by Mary Clay

Black Jack by Lora Leigh

The Tudor Secret by C. W. Gortner

In the Labyrinth of Drakes by Marie Brennan

The Truth War by John MacArthur

Ride Angel Ride: A Biker Erotic Romance (Red Skulls MC) by Stone, Emily

At Any Price (Gaming The System) by Aubrey, Brenna

02. The Shadow Dancers by Jack L. Chalker

Black Alibi by Cornell Woolrich

Sunflowers by Sheramy Bundrick