The Winter Ghosts (19 page)

Authors: Kate Mosse

I made my way back to the signpost and entered the forest once more, feeling like a boy playing truant from school.

The atmosphere felt different. It was partly because there was no mist and the sunlight filtered down through the canopy of mostly bare branches, scattering patches of gold upon the path. But it was also because, thanks to its association now with Fabrissa, I felt at home. I felt part of the landscape, welcome in it, no longer an intruder.

Now I knew where I was going, I covered the ground quickly. Soon I was standing at the place where the twisted roots were visible beneath the scrub. I took a deep breath and began to pull at the undergrowth. It was dense and matted and the frost held everything in its sharp grip. But the fur-lined gloves, although cumbersome, provided good protection, and after a few sharp tugs I managed to pull back a branch, releasing the aroma of damp earth. Sure enough, it revealed a staircase of roots snaking up through the deep evergreen, just as Fabrissa had said.

Bracing my foot against the slope, I kept pulling, a lone contestant in a tug-of-war, until the branch came loose enough for me to duck underneath. I began to climb, hands on my thighs, locking my muscles with each step, like Mallory and Irvine on Everest, going for the top. The roots were slippery and unsafe, and I stumbled onto my hands and knees several times. The steps grew further and further apart, and steeper, too, until in the end it was more like climbing a ladder that twisted all the way up the mountain.

I began to tire. It was exhausting work, always bent double, and I could not imagine how Fabrissa and Jean had managed it in the dead of night and in fear of their lives. But they had. And so could I.

Just when I had reached the limits of my endurance and thought I could go no further, I found myself in the open. I straightened up and stretched my cramped shoulders and arms, then perched on a boulder for a moment to catch my breath and take stock of my surroundings.

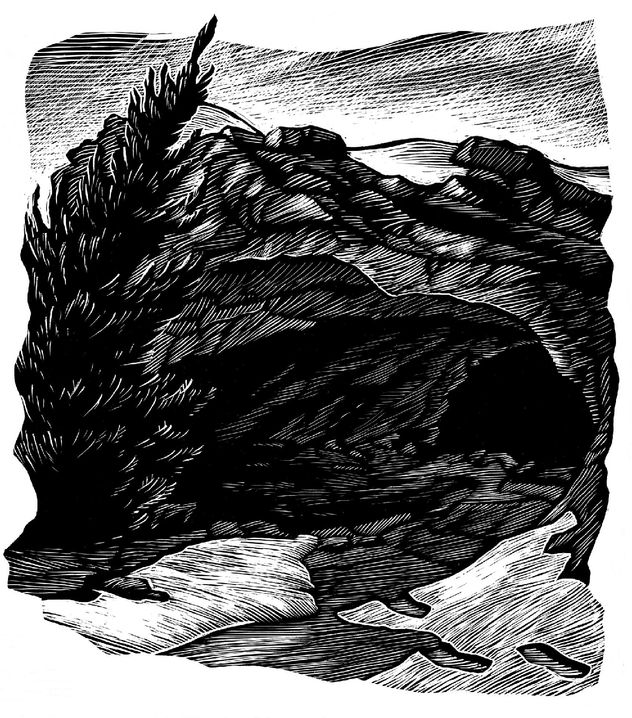

I was in a glade, ringed by trees. Although it wasn’t the plateau I had spied from the road, it wasn’t far from it. I recognised the green circle of leaves and branches, like a May Queen’s crown. Behind me, I could just make out the splash of yellow of my motor car on the grey road. My base camp. And above me, like gaping mouths in the rock face, was a series of openings beneath the jutting escarpments.

I plucked a few stray twigs and branches from my coat, tossed them to the ground, then stood up and prepared to go on.

Did it worry me that there were no signs of human habitation? No wisps of smoke visible? Not even a shepherd’s hut? Certainly no evidence of a village or hamlet? I don’t think it did. At that moment, all I could think about was how I was going to make it to the summit in one piece.

I continued to climb, my thighs shrieking in complaint. Each step was purgatory, an act of endurance, but I found my rhythm and stuck to it. Head down, shoulders forward, knees braced. Sweat trickled down the back of my neck beneath the heavy fur hat, though I knew better than to remove it. My fingers were swimming inside the gloves and my toes were prickly inside my woollen socks and hiking boots. Everything hurt.

But I made it. Now I was directly below the cleft in the rock. From this vantage point, the caves looked to be natural, not man-made, though I was too far away to be certain. A few appeared large enough to harbour a man standing upright. Others only just sufficient for a child to squeeze inside on his hands and knees.

Once I got close enough to see it properly, the beauty of the place took what little breath remained in my lungs. The wind and the rain, the heat and cold, had sculpted the rock over thousands of years. At first glance, it reminded me of photographs I’d seen of tombs in the Holy Land, of the tragedy at Masada. But here in the Ariège, everything was green and grey and brown beneath the dusting of snow, rather than the yellow of the desert.

I glanced at the sky. Counting back from the time at which Breillac and his boys had left me, I estimated it must be somewhere around one o’clock. Time enough.

I walked slowly along the ridge, peering into the hollows and battling down a seeping sense of disappointment. None of them could be the cave within which Fabrissa and her family had taken shelter. Most only went back a yard or two. Nor was there anywhere for her to hide now.

Then I noticed a ribbon of grass, winding up between the rocks. Leaning my shoulder against the side of the mountain to anchor myself, and trying not to think about what would happen if I fell, I edged towards it. Just a few more steps. Don’t look down, Freddie, don’t look down. And then I saw, directly above my head, an overhang of grey rock, like a protruding lip. Beneath it was an opening the shape of a half moon.

Dizzy with relief, I leaned against the broad flank of the mountain and allowed my heart to settle. I’d done it. I mustered my strength to cover the last few feet and, finally, I was there. Fabrissa’s cave.

What was I thinking then? Did I think she would be inside waiting for me, like a game of hide-and-seek at a party? Or perhaps, like a treasure hunt, that there would be secreted in the cave some kind of a clue as to where I should go next? I can’t remember. I can only recall my pride at having faced down the challenge and the exquisite anticipation at the thought of seeing Fabrissa again. For I did still believe she was there, somewhere, trusting me to find her.

‘Fabrissa?’ I called out, but only my own voice answered in the echo.

I peered into the darkness of the cave. At its highest point the opening was about four feet high and five or six feet wide. I turned over a stone with the tip of my boot. The surface was touched with snow but the damp soil beneath was alive with worms and beetles. As my eyes adjusted to the gloom, the short hairs rose on the back of my neck. This was the right cave, I was sure of it. But I felt a sense of apprehension. One could say a premonition. Something was not quite right. I ignored it. I wasn’t going to turn back now.

I slipped the torch from my pocket. The beam was weak, suggesting the battery was low, but it cast a useful light. I lowered my head and stepped inside. It was cool and damp in the entrance but, if anything, a little warmer than outside. I shone the torch around, sending shadows dancing along the jagged grey walls as I edged slowly forward. The ground sloped down beneath my feet, gritty and uneven. Loose stones and small pieces of rock crunched beneath my boots. The daylight grew faint at my back.

Suddenly, I was forced to stop, unable to go another step further. A wall of stone and rubble, braced by a carapace of wood, blocked the passage. Holding the torch higher, I ran my eyes over the obstruction. Rubble held tightly in place by timbers. And, with a gnawing unease, I remembered what Fabrissa had said as we sat beside the dewpond, though it had barely registered at the time: No one came back. Not one.

I pulled at one of the struts of wood. I expected resistance, but it crumbled to powder in my hands. I pulled at another piece and it too came easily free, crumbling in my fist, eaten away by woodworm or termites. Beating down a rising sense of panic, I propped my torch on a stone ledge and attacked the wall. The gloves were too thick to get between the tiny cracks in the facade, so I tossed them aside, the hat, too, and clawed at the rubble with my bare hands.

I don’t know how long I worked, dislodging one stone, then another. The tips of my fingers were bleeding and my upper arms ached, but I was possessed by a wild need to know what lay behind the barricade. Dust billowed into the narrow passageway as I worked.

Finally, there was an opening as big as my hand. I kept going, using rocks as tools to chip away at the hole, then reached my arm in as far as my shoulder and heaved until it was wide enough for me to get through.

I took a deep breath, steeling myself, I suppose, to cope with whatever might be to come, then clambered into the prison of rock and stone.

Bones and Shadows and Dust

Straight away, the smell of air long undisturbed hit me, musty and expectant after its long confinement.

After a few paces, the tunnel curved a little to the left, then immediately opened out into an extraordinary, soaring cavern, the dimensions of a cathedral. In awe at the sheer scale of it, I shone the torch at the walls and up above my head. The beam vanished into the darkness.

‘A city in the mountains,’ I muttered.

For a moment, a feeling of calm came over me, a kind of peace to be in so ancient a place. Their refuge, she’d called it. A refuge that became a tomb.

A long sigh of relief escaped from between my lips. There was nothing to see. Until that moment, I did not realise how much I’d started to fear what I might find.

Fabrissa could not be here. It had taken me long enough to break down the obstruction and it seemed unlikely there would be another way in.

‘But then where are you?’ I whispered into the silence, at last facing what common sense had told me all along. I shook my head. I’d felt so sure I would find her. And, in truth, I somehow felt her presence at my side. Somewhere close by.

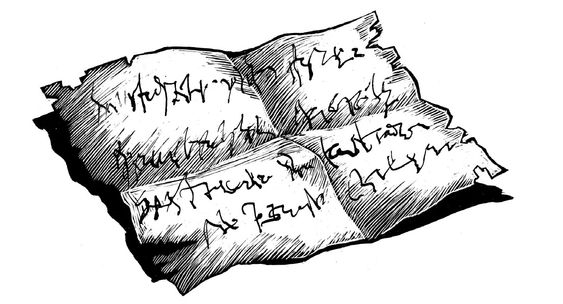

I shone the torch around the cave, sending the beam darting into every crevice. Suddenly, I stopped. Something had struck a discordant note. Taking a step forward, I directed the light towards a protrusion of grey rock emerging at forty-five degrees from the wall. There was something on the ground beside it. I moved forward, keeping the torch steady, until I saw it was a sheet of paper, lying as if impossibly blown there by a sudden gust of wind.

I picked it up. It was rough to the touch, a coarse weave. Parchment rather than vellum or the page of a book, much like the cheap papyrus tourists brought back with them from Cook’s tours of Ancient Egyptian sites. I opened it out. It was covered in scratchy, old-fashioned handwriting, more like music on a stave than printed letters. I could not read it, even when I held the parchment right up to the light.

I folded it and put it in my pocket. There would be time enough to decipher it later.

Looking up, I noticed a fissure in the rock face directly ahead. Shining the torch in front of me, I went to investigate. There was a narrow corridor, a black seam between two massive ribs of the mountain. It was exceedingly narrow and there was no way of telling how long it was, nor where it went. I felt claustrophobic merely looking at it.

But I forced myself to go in. Holding the torch above my head, I inched my way through, sideways on.

‘Take it steady,’ I said, hating the rock pressing on my shoulders. ‘Steady now.’

In the event, the conduit wasn’t so long, and after only a few paces it opened out into a small, self-contained chamber. Unlike the barren outer cave, there was evidence this cavern had been occupied. In the gloom, I could make out a few belongings, the remains of a camp, what might once have been blankets, a snatch of blue and maybe grey, hard to tell the difference in the yellow light of the torch.

‘Fabrissa?’

Why did I call her name once more? I’d already decided she could not be there. But I called out to her all the same, as though a part of me even now hoped she might be there waiting for me.

Other books

Turnagain Love (Sisters of Spirit #1) by Radke, Nancy

Altered Images by Maxine Barry

[Finding Emma 02.5] Dottie's Memories by Steena Holmes

Body Count by James Rouch

Detective Inspector Huss: A Huss Investigation set in Sweden, Vol. 1 by Tursten, Helen

Three Wishes by Lisa T. Bergren, Lisa Tawn Bergren

A Perfect Christmas by Page, Lynda

A Shattering Crime by Jennifer McAndrews

Highlander Unchained by McCarty, Monica

tmp0 by Veronica Jones