The Wind in the Willows (24 page)

Read The Wind in the Willows Online

Authors: Kenneth Grahame

‘O, have they!’ said Toad, getting up and seizing a stick. ‘I’ll jolly soon see about that!’

‘It’s no good, Toad!’ called the Rat after him. ‘You’d better come back and sit down; you’ll only get into trouble.’

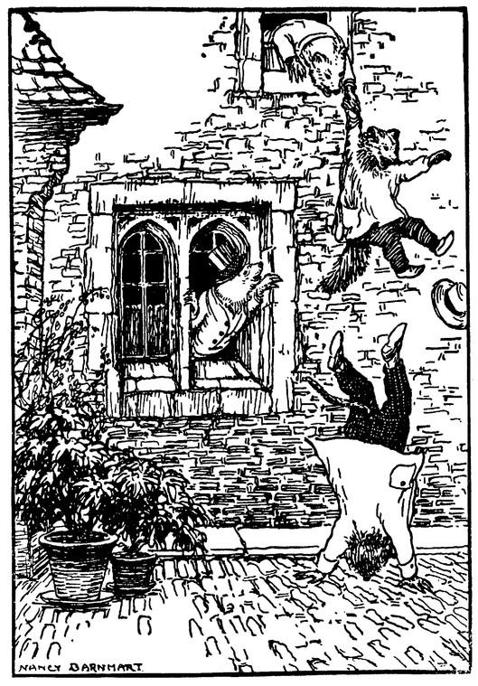

But the Toad was off, and there was no holding him. He marched rapidly down the road, his stick over his shoulder, fuming and muttering to himself in his anger, till he got near his front gate, when suddenly there popped up from behind the palings a long yellow ferret with a gun.

‘Who comes there?’ said the ferret sharply.

‘Stuff and nonsense!’ said Toad very angrily. ‘What do you mean by talking like that to me? Come out of it at once, or I’ll—’

The ferret said never a word, but he brought his gun up to his shoulder. Toad prudently dropped flat in the road, and Bang! a bullet whistled over his head.

The startled Toad scrambled to his feet and scampered off down the road as hard as he could; and as he ran he heard the ferret laughing, and other horrid thin little laughs taking it up and carrying on the sound.

He went back, very crestfallen, and told the Water Rat.

‘What did I tell you?’ said the Rat. ‘It’s no good. They’ve got sentries posted, and they are all armed. You must just wait.’

Still, Toad was not inclined to give in all at once. So he got out the boat, and set off rowing up the river to where the garden front of Toad Hall came down to the water-side.

Arriving within sight of his old home, he rested on his oars and surveyed the land cautiously. All seemed very peaceful and deserted and quiet. He could see the whole front of Toad Hall, glowing in the evening sunshine, the pigeons settling by twos and threes along the straight line of the roof; the garden, a blaze of flowers; the creek that led up to the boat-house, the little wooden bridge that crossed it; all tranquil, uninhabited, apparently waiting for his return. He would try the boat-house first, he thought. Very warily he paddled up to the mouth of the creek, and was just passing under the bridge, when...

Crash!

A great stone, dropped from above, smashed through the bottom of the boat. It filled and sank, and Toad found himself struggling in deep water. Looking up, he saw two stoats leaning over the parapet of the bridge and watching him with great glee. ‘It will be your head next time, Toady!’ they called out to him. The indignant Toad swam to shore, while the stoats laughed and laughed, supporting each other, and laughed again, till they nearly had two fits—that is, one fit each, of course.

The Toad retraced his weary way on foot, and related his disappointing experiences to the Water Rat once more.

‘Well,

what

did I tell you?’ said the Rat very crossly. ‘And, now, look here! See what you’ve been and done! Lost me my boat that I was so fond of, that’s what you’ve done! And simply ruined that nice suit of clothes that I lent you! Really, Toad, of all the trying animals—I wonder you manage to keep any friends at all!’

The Toad saw at once how wrongly and foolishly he had acted. He admitted his errors and wrong-headedness and made a full apology to Rat for losing his boat and spoiling his clothes. And he wound up by saying, with that frank self-surrender which always disarmed his friends’ criticism and won them back to his side, ‘Ratty! I see that I have been a headstrong and a wilful Toad! Henceforth, believe me, I will be humble and submissive, and will take no action without your kind advice and full approval!’

‘If that is really so,’ said the good-natured Rat, already appeased, then my advice to you is, considering the lateness of the hour, to sit down and have your supper, which will be on the table in a minute, and be very patient. For I am convinced that we can do nothing until we have seen the Mole and the Badger, and heard their latest news, and held conference and taken their advice in this difficult matter.’

‘O, ah, yes, of course, the Mole and the Badger,’ said Toad lightly. ‘What’s become of them, the dear fellows? I had forgotten all about them.’

‘Well may you ask!’ said the Rat reproachfully. ‘While you were riding about the country in expensive motor-cars, and galloping proudly on blood-horses, and breakfasting on the fat of the land, those two poor devoted animals have been camping out in the open, in every sort of weather, living very rough by day and lying very hard by night; watching over your house, patrolling your boundaries, keeping a constant eye on the stoats and the weasels, scheming and planning and contriving how to get your property back for you. You don’t deserve to have such true and loyal friends, Toad, you don’t, really. Some day, when it’s too late, you’ll be sorry you didn’t value them more while you had them!’

‘I’m an ungrateful beast, I know,’ sobbed Toad, shedding bitter tears. ‘Let me go out and find them, out into the cold, dark night, and share their hardships, and try and prove by—Hold on a bit! Surely I heard the chink of dishes on a tray! Supper’s here at last, hooray! Come on, Ratty!’

The Rat remembered that poor Toad had been on prison fare for a considerable time, and that large allowances had therefore to be made. He followed him to the table accordingly, and hospitably encouraged him in his gallant efforts to make up for past privations.

They had just finished their meal and resumed their arm-chairs, when there came a heavy knock at the door.

Toad was nervous, but the Rat, nodding mysteriously at him, went straight up to the door and opened it, and in walked Mr. Badger.

He had all the appearance of one who for some nights had been kept away from home and all its little comforts and conveniences. His shoes were covered with mud, and he was looking very rough and tousled; but then he had never been a very smart man, the Badger, at the best of times. He came solemnly up to Toad, shook him by the paw, and said, ‘Welcome home, Toad! Alas! what am I saying? Home, indeed! This is a poor home-coming. Unhappy Toad!’ Then he turned his back on him, sat down to the table, drew his chair up, and helped himself to a large slice of cold pie.

Toad was quite alarmed at this very serious and portentous style of greeting; but the Rat whispered to him, ‘Never mind; don’t take any notice; and don’t say anything to him just yet. He’s always rather low and despondent when he’s wanting his victuals. In half an hour’s time he’ll be quite a different animal.’

So they waited in silence, and presently there came another and a lighter knock. The Rat, with a nod to Toad, went to the door and ushered in the Mole, very shabby and unwashed, with bits of hay and straw sticking in his fur.

‘Hooray! Here’s old Toad!’ cried the Mole, his face beaming. ‘Fancy having you back again!’ And he began to dance round him. ‘We never dreamt you would turn up so soon! Why, you must have managed to escape, you clever, ingenious, intelligent Toad!’

The Rat, alarmed, pulled him by the elbow; but it was too late. Toad was puffing and swelling already.

‘Clever? O no!’ he said. ‘I’m not really clever, according to my friends. I’ve only broken out of the strongest prison in England, that’s all! And captured a railway train and escaped on it, that’s all! And disguised myself and gone about the country humbugging everybody, that’s all! O no! I’m a stupid ass, I am! I’ll tell you one or two of my little adventures, Mole, and you shall judge for yourself!’

‘Well, well,’ said the Mole, moving towards the supper-table; ‘supposing you talk while I eat. Not a bite since breakfast! O my! O my!’ And he sat down and helped himself liberally to cold beef and pickles.

Toad straddled on the hearth-rug, thrust his paw into his trouser-pocket and pulled out a handful of silver. ‘Look at that!’ he cried, displaying it. ‘That’s not so bad, is it, for a few minutes’ work? And how do you think I done it, Mole? Horse-dealing! That’s how I done it!’

‘Go on, Toad,’ said the Mole, immensely interested.

‘Toad, do be quiet, please!’ said the Rat. ‘And don’t you egg

cb

him on, Mole, when you know what he is; but please tell us as soon as possible what the position is, and what’s best to be done, now that Toad is back at last.’

‘The position’s about as bad as it can be,’ replied the Mole grumpily; ‘and as for what’s to be done, why, blest if I know! The Badger and I have been round and round the place, by night and by day; always the same thing. Sentries posted everywhere, guns poked out at us, stones thrown at us; always an animal on the look-out, and when they see us, my! how they do laugh! That’s what annoys me most!’

‘It’s a very difficult situation,’ said the Rat, reflecting deeply. ‘But I think I see now, in the depths of my mind, what Toad really ought to do. I will tell you. He ought to—’

‘No, he oughtn’t!’ shouted the Mole, with his mouth full. ‘Nothing of the sort! You don’t understand. What he ought to do is, he ought to—’

‘Well, I shan’t do it, anyway!’ cried Toad, getting excited. ‘I’m not going to be ordered about by you fellows! It’s my house we’re talking about, and I know exactly what to do, and I’ll tell you. I’m going to—’

By this time they were all three talking at once, at the top of their voices, and the noise was simply deafening, when a thin, dry voice made itself heard, saying, ‘Be quiet at once, all of you!’ and instantly every one was silent.

It was the Badger, who, having finished his pie, had turned round in his chair and was looking at them severely. When he saw that he had secured their attention, and that they were evidently waiting for him to address them, he turned back to the table again and reached out for the cheese. And so great was the respect commanded by the solid qualities of that admirable animal, that not another word was uttered until he had quite finished his repast and brushed the crumbs from his knees. The Toad fidgeted a good deal, but the Rat held him firmly down.

When the Badger had quite done, he got up from his seat and stood before the fireplace, reflecting deeply. At last he spoke.

‘Toad!’ he said severely. ‘You bad, troublesome little animal! Aren’t you ashamed of yourself? What do you think your father, my old friend, would have said if he had been here tonight, and had known of all your goings-on?’

Toad, who was on the sofa by this time, with his legs up, rolled over on his face, shaken by sobs of contrition.

‘There, there!’ went on the Badger more kindly. ‘Never mind. Stop crying. We’re going to let bygones be bygones, and try and turn over a new leaf. But what the Mole says is quite true. The stoats are on guard, at every point, and they make the best sentinels in the world. It’s quite useless to think of attacking the place. They’re too strong for us.’

‘Then it’s all over,’ sobbed the Toad, crying into the sofa cushions. ‘I shall go and enlist for a soldier, and never see my dear Toad Hall any more!’

‘Come, cheer up, Toady!’ said the Badger. ‘There are more ways of getting back a place than taking it by storm. I haven’t said my last word yet. Now I’m going to tell you a great secret.’

Toad sat up slowly and dried his eyes. Secrets had an immense attraction for him, because he never could keep one, and he enjoyed the sort of unhallowed thrill he experienced when he went and told another animal, after having faithfully promised not to.

‘There—is—an—underground—passage,’ said the Badger impressively, ‘that leads from the river bank quite near here, right up into the middle of Toad Hall.’

‘O, nonsense! Badger,’ said Toad rather airily. ‘You’ve been listening to some of the yarns they spin in the public-houses about here. I know every inch of Toad Hall, inside and out. Nothing of the sort, I do assure you!’

‘My young friend,’ said the Badger with great severity, ‘your father, who was a worthy animal—a lot worthier than some others I know—was a particular friend of mine, and told me a great deal he wouldn’t have dreamt of telling you. He discovered that passage—he didn’t make it, of course; that was done hundreds of years before he ever came to live there—and he repaired it and cleaned it out, because he thought it might come in useful some day, in case of trouble or danger; and he showed it to me. “Don’t let my son know about it,” he said. “He’s a good boy, but very light and volatile in character, and simply cannot hold his tongue. If he’s ever in a real fix, and it would be of use to him, you may tell him about the secret passage; but not before.” ’

The other animals looked hard at Toad to see how he would take it. Toad was inclined to be sulky at first; but he brightened up immediately, like the good fellow he was.

‘Well, well,’ he said; ‘perhaps I am a bit of a talker. A popular fellow such as I am—my friends get round me—we chaff, we sparkle, we tell witty stories—and somehow my tongue gets wagging. I have the gift of conversation. I’ve been told I ought to have a salon,

cc

whatever that may be. Never mind. Go on, Badger. How’s this passage of yours going to help us?’

‘I’ve found out a thing or two lately,’ continued the Badger. ‘I got Otter to disguise himself as a sweep and call at the back door with brushes over his shoulder, asking for a job. There’s going to be a big banquet tomorrow night. It’s somebody’s birthday—the Chief Weasel’s, I believe—and all the weasels will be gathered together in the dining-hall, eating and drinking and laughing and carrying on, suspecting nothing. No guns, no swords, no sticks, no arms of any sort whatever!’