The Willows in Winter (17 page)

Read The Willows in Winter Online

Authors: William Horwood,Patrick Benson

Tags: #Young Adult, #Animals, #Childrens, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Classics

“My Lord —” the other began.

“‘My Lord’!” repeated Toad to himself

desperately

This

was not good, not good at all. He

quieted himself and listened to what else they said.

“My Lord Bishop,” the speaker continued.

Toad relaxed somewhat, for a Bishop, whatever

the colour of his cloth, might be expected to be charitable in a case like his.

This was most promising, and Toad was almost inclined to call out right away

and reveal himself, for a Bishop would take care of him. But some instinct kept

him silent.

“My Lord Bishop, this particular species is the

only one of its kind in all of

Commissioner here knows.”

“That’s right’ said a cruel, harsh voice.

“‘Commissioner’!” muttered Toad. “That sounds

to me ominously like an elevated police officer down below, a Commissioner of

Police no less. From such a one I can expect no justice, no quarter.”

But then Toad heard something else, something

worse,

something

dreadful.

For the Police Commissioner continued, with a

joviality that almost froze Toad’s heart, “Well, all I can say is that if so

splendid a specimen as this tree were stolen, or vandalised in any way, then I

would not give the perpetrator a dog’s chance in

your

High Court, Judge!”

“‘Judge’?!” gasped Toad, his legs beginning to

feel itchy again.

“And ‘High Court’!

That is more than

an ordinary Judge — that is a Very Honourable and Senior Judge. That might

almost be the Lord Chancellor himself!”

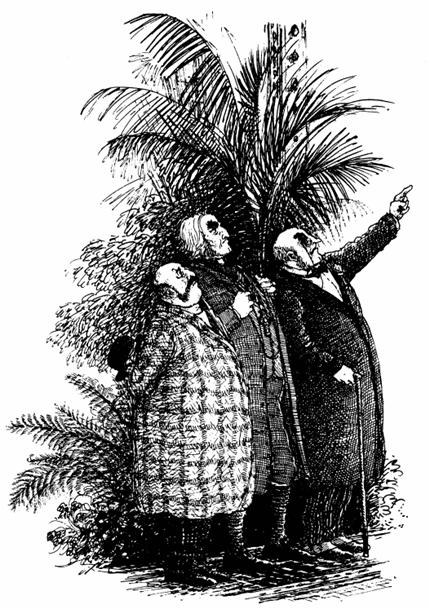

The three below showed no signs of moving, but

talked on in an amiable way till Toad, peering down to see what he could, saw

one of them peering up, and then stepping forward and to one side to get a

better view.

“My Lord!” the inquisitive and unpleasant Judge

called out — for the other two seemed about to move on. “Tell me, do you keep

tropical beasts in here as well, perhaps for purposes of fertilizing the

blooms, or the natural elimination of pests?”

“You mean tropical insects, spiders, that sort

of thing?”

Insects! Spiders!

How dreadful

were the

creepings

and the

crawlings

and

the

itchings

about Toad’s

lower half now. How

near he was to crying out for mercy A life sentence in that drear dungeon from

which he had escaped so long before — and so cleverly — seemed a holiday

compared to the sufferings he was now being forced to endure.

“I was thinking of something rather larger, as

a matter of fact.”

“You mean fruit-eating bats, or the larger sort

of snake or Bats! Snakes!

“No

no

, something

larger like, well, I am not quite sure — like

that!

”

It was no

good,

Toad

could endure it no more. They had seen him, and if they had not then how long

might he be left here after they had gone, to be frozen above, while below,

something worse: basted by the humid heat, and then nibbled, and eaten and

stung by spiders and insects, horrible snakes and fruit bats!

“Help!” cried Toad. “I am stuck! Free

me

and I shall go quietly!”

“Goodness me!” exclaimed My Lord Bishop.

“A thief!” cried the Commissioner of Police.

“We had best not judge till we have heard all

the evidence’ said His Honour, Justice of the High Court.

“Help!” cried Toad. “I am an unfortunate

aviator, who has fallen on hard times!”

As his muffled cries came down to them, others

came running and there was great consternation down below though Toad was too

terrified, too panicked, too eager to escape the purgatory of his position to

listen to what was said. If only his top half might be comforted by hot water

bottles, and his lower half packed with ice so that his body might recover

something of its equilibrium, then he might be able to think clearly once more,

and plan his escape.

But as they came to his help he did at least

hear the declarations below that a flying machine had been seen to go over,

that an aviator had plunged to the ground and that this poor fellow stuck above

might be he. For the moment — and for Toad’s continuing liberty this was the

most important thing — for the moment, at least, none guessed that Toad was

Toad.

In one respect, at least, Toad’s presence of

mind did not desert him. He guessed that once his flying gear was removed the

game might be up. So when the glasshouse men ascended their ladders, and

carefully came to free him, he said in a pathetic voice, “Do not take off my

jacket or headgear, please do not, for I am nearly perishing with cold!”

Then, remembering something about the perils of

deep-sea diving, he added knowledgeably, “It has to do with oxygen in the

blood, you know Remove my headgear and I die!”

This appeal was heard and obeyed, and Toad at

last felt himself being lowered onto the hothouse floor, there to be ministered

to by the many people now milling about, as his mind swam away into fevered and

humid unconsciousness.

VIII

Back from Beyond

When Toad drifted back to consciousness he felt his eyelids gently

touched by a subdued light, and he seemed to be wallowing in a caressing

atmosphere filled with the healing scents of lavender and rosemary.

He slowly opened his eyes to find his head

supported by the softest of down pillows, encased in the finest of linen

pillowcases, and his hands resting upon the crispest and whitest of turned-down

sheets, beyond which, ruffled only by his now blissfully cool legs and feet,

was a quilted eiderdown overlaid with a silken bedspread.

He was gratified to find himself still attired

just as he had been, complete with goggles, his identity as aviator thus far

seemingly intact.

He peered about suspiciously before taking the

goggles off so that he might take a better look at where he was, and found

himself in a large and spacious bedchamber, about as large as the refectory in

Toad Hall itself.

He

lay

, like a

well—framed picture, in the largest, highest and grandest of mahogany

four-poster beds. Toad sighed with contentment and lazily examined his

surroundings from his supine position. Across the room, though not quite

opposite his bed, was a splendid coal fire, its flames warm and merry. Off to

his left was an exterior wall, with two tall windows, reaching nearly as high

as the lofty ceiling, and nearly as low as the floor, and curtained with the

folds and drapes and hangings of the softest, palest of pale pink and mauve

materials.

The curtains were not fully drawn, and from

what he .could see the windows offered a view of the very extensive grounds

above which he had flown, and down onto which fate had decreed he fall.

Shifting his gaze further about the room, Toad saw with pleasure that, as if to

match the room’s general magnificence, its wardrobes were of the finest and

shiniest, and its dressing table of the most elegant, and there, on its fluted

washstand, a Worcester bowl awaited his leisured use, and within it, steaming

amiably, a huge jug containing hot rose-scented water.

Toad sighed once more and wiggled his feet,

easing himself first to one side and then the other to feel how extensive and

lasting his wounds and injuries might be. Certainly he ached, though not as

much as he might have done, yet sufficiently to moan and groan a little to

himself.

“Nothing broken,” he whispered feebly, “I

think.” Then, raising first one arm and then the other, he pulled the sheets

down a little for a moment, and added, “And no sign of blood or mortal wound. I

shall survive! I shall live!”

He swallowed, and then felt his forehead, to

test perhaps the advance of the pneumonia he had earlier feared would take hold

of him.

“I have fought it off! I am still strong! I

have been to the extremes of endurance without too much harm!”

Thus reassured, he glanced towards the windows

once again and, wishing to see something of the world beyond, he leapt nimbly

out of bed, went to the door to see that no person was outside it, turned the

key in its lock and strode over to the nearest window.

It was now nearly evening, though not yet dark

enough outside to prevent him seeing that the view did not so much take in all

the grounds, but rather offered him what was surely the most elegant part, the

most striking turn and vista of lawn, of balustrade, of choice rose-beds and

most ancient and established of trees.

“Splendid,” he said, “and just what I would

expect of a House honoured by a visiting aviator such as myself. However, we

must be careful: this place appears riddled with Judges, Commissioners of

Police and malevolent Lords, and as I saw on my descent, the Castle with its

dungeon is not far off. Therefore, I must escape as soon as —But he was

interrupted in his thoughts by a discreet turning of the door handle, and then

an even more discreet knock, followed by the concerned voice of an elderly male

saying, “Sir! Are you quite all right?”

Toad hastily closed the curtains, leapt back

into bed with alacrity and in a tremulous voice called back, “I am ill, gravely

ill I think. I should not have got up.

“The door is locked, sir; I cannot come in to

give you the food and drink which His Lordship has sent up. Shall I leave it

outside, perhaps?”

All this was spoken in an agreeably servile way

by one whose only task in life, as it seemed to Toad, was to serve Toad, and it

seemed a pity not to oblige him. The more so if food and drink was at hand, the

mention of

which caused Toad to feel immediately hungry and

thirsty.

“Wait, while I struggle to the door,” called

out Toad pathetically, which he did, very quickly.

He opened it a mite and peering out saw a

butler standing there, tray in hand.

“I am not well at all, and the light disturbs

my eyes,” whispered Toad. “I pray you let me get back into bed before you come

in, and do not bring light into the room when you do — or, if you must, for

though I can drink little and eat less it would be a shame not to at least try,

place the light far from my bed.”

This was a pretty speech, but one which Toad

sensed might appear a little too robust, so he sighed and moaned and groaned a

little more, provoking the kindly butler to make soft sounds of concern.