The White Horse King: The Life of Alfred the Great (7 page)

Read The White Horse King: The Life of Alfred the Great Online

Authors: Benjamin R. Merkle

Tags: #ebook, #book

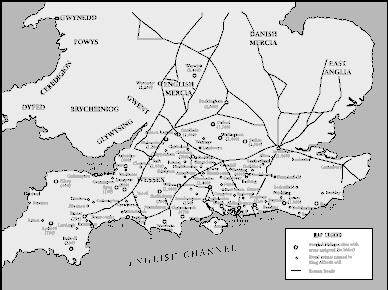

There was no hope of aid from Northumbria, East Anglia, or Mercia. All the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had either been conquered or were so entirely intimidated by the Danish armies that coming to the aid of Wessex was out of the question, leaving Wessex to stand alone. As the Vikings advanced into the heart of Wessex, intending to ravage the land as they had throughout Northumbria and East Anglia, the men of Wessex were left with little choice. They rushed to cut off the Viking advance, intercepting the Danish raiders at Ashdown, where they were able to force the Vikings to face them in battle.

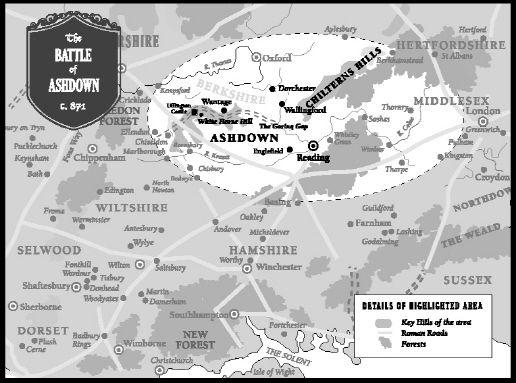

Since Ashdown was not the name of a specific point, but rather a general term for the entire stretch of the Berkshire downs, the exact location of the battlefield is a puzzle to modern historians. The clues given by the ninth-century accounts of Alfred’s movements are difficult to interpret with any degree of certainty. Asser, Alfred’s friend and biographer, recorded that the Latin name for Ashdown was

mons

fraxini

, or “the hill of the ash.” But the only landmark identified by Asser was a small and solitary thorn tree around which the battle raged. That lonely thorn tree must have etched itself on the memories of the Ashdown veterans, since Asser took the time to mention in his brief description of the battle how he had seen that very thorn tree.

The prevailing theory that the battle of Ashdown happened at Kingstanding Hill, not far from the village of Moulsford on the banks of the Thames, is incredibly speculative. The theory is based on the assumption that the Vikings, after having successfully held off the forces of Wessex at Reading,

may

have immediately turned their attentions north to the military stronghold at Wallingford and the riches of the wealthy abbey at Abingdon. If the Vikings had done so, then a strategic position for repulsing the Viking attack

might

have been Kingstanding Hill. And though this is all plausible, it rests on a series of guesses with no actual historical evidence to back up the speculation.

© MARK ROSS/SURFACEWORKS

The most popular traditional account identifies Ashdown with what is now known as Whitehorse Hill, an imposing hill that looms over the low-lying Berkshire Downs. It stands around nine hundred feet above sea level, making it the tallest point from miles in every direction. The top of the hill had been converted more than a thousand years before the time of Alfred into the Iron Age fortress of Uffington Castle. In the ninth century, that castle was known as Ashburg—the city of Ash. Ashburg was closely associated with Ashdown, and it would have been completely natural to refer to a battle outside the gates of Ashburg as the battle of Ashdown. The outer fortifications would have provided an imposing defensive wall for the raiding army. The height of the hill supplies a commanding view in all directions, making it an ideal position from which the Viking camp could have easily watched for the approaching Wessex army.

© Gorilla Poet Productions

Carved into the turf of the northwest slope of the hill, near its summit, is the mysterious chalk outline of a galloping white horse.

The charging horse, in its perpetual career, stretches almost four hundred feet along the top of the steepest slope of the hill. Ancient artists first dug a maze of trenches across the hillside and then filled the trenches with chalk rubble in order to trace the white figure into the hillside. Though the earliest reference to the white horse comes from the eleventh century AD, modern dating techniques have suggested that the horse could have been cut into the hillside as early as 1000 BC. No clear account of the horse, who made it, or why it was made can be given.

The white horse has gathered many of the myths of history to itself, and those myths have grown more and more fantastical grazing on the green slopes of the vale. King Arthur, Saint George, and Alfred the Great are all claimed by the white horse, and the region surrounding the hillside is littered with the relics of their legends. Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon, is said to have fought a victorious battle in the valley below. One story claims that Whitehorse Hill is actually Badon Hill, the site of one of Arthur’s great victories.

The Norse god of blacksmithing, Wayland, is said to have manned his forge a mile from Whitehorse Hill at Wayland’s Smithy, a Neolithic barrow. Some stories have Wayland himself forging Arthur’s great sword, Excalibur. Some say that, once a year, the white horse leaves the hillside and walks down to the valley below (known 46 as the “manger”) to graze. But others insist that the white horse won’t leave the hillside until King Arthur returns. And then he won’t just graze in the manger; he will dance along the Berkshire Downs to welcome the king home.

Other legends insist that the carving on Whitehorse Hill does not depict a horse at all, but rather a dragon—Saint George’s dragon. One historian claimed that the conspicuous little knob bulging out of the valley below Whitehorse Hill is the very spot where Saint George killed his dragon. The poisonous blood of the slain dragon spilled out on the top of the hill, burning a bare patch into the ground where the dragon lay—a bare patch that endures to this day. The association with Saint George’s dragon is so strong that the hill is now known simply as “Dragon Hill.” However, some deny that George killed his dragon on the mountain. They insist that the strange mound

is

the dragon, or more precisely, his burial mound.

1

Alfred’s own story is not without embellishment. According to one legend, Alfred gathered the men of Wessex to the battle of Ashdown by using the ghostly blast of the blowing stone, a peculiar hunk of sarsen stone that was found on the top of a nearby hill. The stone stands around three feet high and is pierced throughout by a maze of holes, some going only a few inches and stopping and some threading all the way through the stone via a network of winding chambers and chasms. The stone now sits in the front yard of a cottage not far from Blowing Stone Hill, where it once sat. The hole that serves as a mouthpiece is found 47 on top of the stone, its rim polished by centuries of lips pressing it smooth. Passersby are still welcome to give the stone a toot. The occupant of the cottage, I imagine, could be identified by a jittery, haunted aspect and poor hearing.

The numerous fantastical elements attributed to Whitehorse Hill have had the effect of making the whole setting seem too mystical to be true. It has become the sort of setting that scholars tend to wave their hands at and say, “It’s all shrouded in myth. We’re not even sure if there ever really was a Whitehorse Hill.” But there is the horse, ghostly white and galloping along the hillside, whether or not we believe in his countless legends. We know that there really was an Alfred, who stood and faced the Viking invaders on the battlefield in AD 871. And though we may not know for certain that Whitehorse Hill was the site of the battle, it is easily the most likely candidate.

When Alfred composed his will many years later, he left three of his fifty-five estates to his wife Ealswith. One was Wantage, the place of his birth. The other two were Edington and Lambourn. Edington was the site of one of Alfred’s later victories over Viking forces. Lambourn was an estate just south of Whitehorse Hill, the site where, according to legend, Alfred gathered his forces just before the battle of Ashdown. It would seem that when Alfred composed his will, he picked three properties filled with personal significance to give to his wife. Last, it should be remembered that the only identifying feature the historian Asser gave for the battlefield of Ashdown was a solitary thorn tree. Oddly, the Anglo-Saxon charter describing the Whitehorse hillside named a solitary thorn tree as one of the identifying features of the property line.

Though these clues may not form definitive proof that 48 Whitehorse Hill was the site of the battle of Ashdown, they present a much stronger case than any of the other proposed locations. One certainly begins to wonder what caused scholars to become so sensitive about the legend of the white horse and forced them to prefer other more speculative options. Virtually the only thing that makes Kingstanding Hill more preferable than Whitehorse Hill is that it is not legendary.

Kingstanding Hill is not smothered with legends and has a non-mythical, unromanticized, scholarly plainness about it. It can be slipped into a footnote without attracting attention to itself, whereas the Whitehorse immediately evokes snorts and guffaws because of the preposterously fantastical legends heaped onto it. But this is such a remarkably miserly way to interpret the evidence. It is more likely that the many layers of legends surrounding Whitehorse Hill have accumulated there because, as the location of the great battle of Ashdown, it was assumed that other spectacular events must have happened there as well.

© MARK ROSS/SURFACE

The Viking forces carefully chose their battle positions before the soldiers of Wessex had arrived at Ashdown. Bagsecg and Halfdan, the two Viking kings, selected the highest point on the hillside for their defensive position, lining up their men along the crest of the ridge and forcing the Wessex army to attack from below. Though the Vikings may have been using horses or ponies to speed their travel, the horses would have been released before the battle because the Vikings preferred to fight on their feet rather than on horseback. The Danish army was then divided into two units—one commanded by the two Viking kings, Bagsecg and Halfdan, and the other commanded by a collection of the Viking earls.

Though the Vikings, as a result of cunning and not cowardice, may have frequently used a strategy that minimized engaging in the sort of open-field combat they were about to face the Viking soldiers were nothing but battle hungry on that bitterly cold morning. Like hungry wolves, they waited uneasy, almost parched with blood thirst. They sat on the ridge, watching for the approach of the Wessex soldiers from below, testing their blades and tightening their armor, promising their gods a grisly sacrifice of victims soon to be offered up on the battlefield.