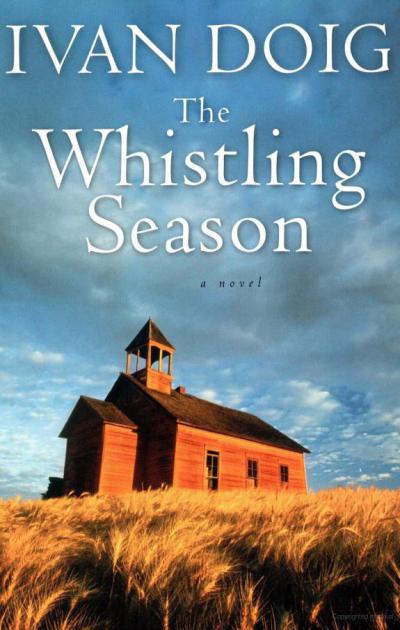

The Whistling Season

Read The Whistling Season Online

Authors: Ivan Doig

Copyright © 2006 by Ivan Doig

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should

be mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Doig, Ivan.

The whistling season/Ivan Doigâ1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Brothers and sistersâFiction. 2. Irrigation projectsâFiction.

3. HousekeepersâFiction. 4. TeachersâFiction. 5. WidowersâFiction.

6. MontanaâFiction. I. Title.

PS3554.O415W48 2006

813'.54âdc22 2005025457

ISBN-13: 978-0-15-101237-4 ISBN-10: 0-15-101237-7

Text set in Adobe Caslon

Designed by Linda Lockowitz

Printed in the United States of America

First edition

C E G I K J H F D

To Ann and Marshall Nelson

1In at the beginning

and reliably fantastic all the way

W

HEN I VISIT THE BACK CORNERS OF MY LIFE AGAIN AFTER

so long a time, littlest things jump out first. The oilcloth, tiny blue windmills on white squares, worn to colorless smears at our four places at the kitchen table. Our father's pungent coffee, so strong it was almost ambulatory, which he gulped down from suppertime until bedtime and then slept serenely as a sphinx. The pesky wind, the one element we could count on at Marias Coulee, whistling into some weather-cracked cranny of this house as if invited in.

That night we were at our accustomed spots around the table, Toby coloring a battle between pirate ships as fast as his hand could go while I was at my schoolbook, and Damon, who should have been at his, absorbed in a secretive game of his own devising called domino solitaire. At the head of the table, the presiding sound was the occasional turning of a newspaper page. One has to imagine our father reading with his finger, down the column of rarely helpful want ads in the

Westwater Gazette

that had come in our week's gunnysack of mail and provisions, in his customary search for a colossal but underpriced team of

workhorses, and that inquisitive finger now stubbing to a stop at one particular heading. To this day I can hear the signal of amusement that line of type drew out of him. Father had a short, sniffing way of laughing, as if anything funny had to prove it to his nose first.

I glanced up from my geography lesson to discover the newspaper making its way in my direction. Father's thumb was crimped down onto the heading of the ad like the holder of a divining rod striking water. "Paul, better see this. Read it to the multitude."

I did so, Damon and Toby halting what they were at to try to take in those five simple yet confounding words:

C

AN'T

C

OOK

B

UT

D

OESN'T

B

ITE

.

Meal-making was not a joking matter in our household. Father, though, continued to look pleased as could be and nodded for me to keep reading aloud.

Â

Housekeeping position sought by widow.

Sound morals, exceptional disposition. No

culinary skills, but A-l in all other household

tasks. Salary negotiable, but must include

railroad fare to Montana locality; first

year of peerless care for your home thereby

guaranteed. Respond to Boxholder, Box 19,

Lowry Hill Postal Station, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Â

Minneapolis was a thousand miles to the east, out of immediate reach even of the circumference of enthusiasm we could see growing in our father. But his response wasted no time in trying itself out on the three of us. "Boys? Boys, what would you think of our getting a housekeeper?"

"Would she do the milking?" asked Damon, ever the cagey one.

That slowed up Father only for a moment. Delineation of house chores and barn chores that might be construed as a logical extension of our domestic upkeep was exactly the sort of issue he liked to take on. "Astutely put, Damon. I see no reason why we can't stipulate that churning the butter begins at the point of the cow."

Already keyed up, Toby wanted to know, "Where she gonna sleep?"

Father was all too ready for this one. "George and Rae have their spare room going to waste now that the teacher doesn't have to board with them." His enthusiasm really was expanding in a hurry. Now our relatives, on the homestead next to ours, were in the market for a lodger, a lack as unbeknownst to them as our need for a housekeeper had been to us two minutes ago.

"Lowry Hill." Father had turned back to the boldface little advertisement as if already in conversation with it. "If I'm not mistaken, that's the cream of Minneapolis."

I hated to point out the obvious, but that chore seemed to go with being the oldest son of Oliver Milliron.

"Father, we're pretty much used to the house muss by now. It's the cooking part you say you wouldn't wish on your worst enemy."

He knewâwe all knewâI had him there.

Damon's head swiveled, and then Toby's, to see how he could possibly deal with this. For miles around, our household was regarded with something like a low fever of consternation by every woman worthy of her apron. As homestead life went, we were relatively prosperous and "bad off," as it was termed, at the same time. Prosperity, such as it was, consisted of payments

coming in from the sale of Father's drayage business back in Manitowoc, Wisconsin. The "bad off" proportion of our situation was the year-old grave marker in the Marias Coulee cemetery. Its inscription, chiseled into all our hearts as well as the stone, read

Florence Milliron, Beloved Wife and Mother (1874â1908).

As much as each of the four of us missed her at other times, mealtimes were a kind of tribal low point where we contemplated whatever Father had managed to fight onto the table this time. "Tovers, everyone's old favorite!" he was apt to announce desperately as he set before us leftover hash on its way to becoming leftover stew.

Now he resorted to a lengthy slurp of his infamous coffee and came up with a response to me, if not exactly a reply:

"These want ads, you know, Paulâthere's always some give to them. It only takes a little bargaining. If I were a wagering man, I'd lay money Mrs. Minneapolis there isn't as shy around a cookstove as she makes herself out to be."

"Butâ" My index finger pinned down the five tablet-bold words of the heading.

"The woman was in a marriage," Father patiently overrode the evidence of the newsprint, "so she had to have functioned in a kitchen."

With thirteen-year-old sagacity, I pointed out: "Unless her husband starved out."

"Hooey. Every woman can cook. Paul, get out your good pen and paper."

***

T

HIS JILTED OLD HOUSE AND ALL THAT IT HOLDS, EVEN

empty. If I have learned anything in a lifetime spent overseeing schools, it is that childhood is the one story that stands by itself in every soul. As surely as a compass needle knows north, that is what draws me to these remindful rooms as if the answer I need by the end of this day is written in the dust that carpets them.

The wrinkled calendar on the parlor wall stops me in my tracks. It of course has not changed since my last time here. Nineteen fifty-two. Five years, so quickly passed, since the Marias Coulee school board begged the vacant old place from me for a month while they repaired the roof of their teacherage and I had to come out from the department in Helena to go over matters with them. What I am startled to see is that the leaf showing on the calendarâOctoberâsomehow stays right across all the years: that 1909 evening of

Paul, get out your good pen and paper,

the lonely teacher's tacking up of something to relieve these bare walls so long after that, and my visit now under such a changed sky of history.

The slyness of calendars should not surprise me, I suppose. Passing the newly painted one-room school, our school, this morning as I drove out in my state government car, all at once I was again at that juncture of time when Damon and Toby and I, each in our turn, first began to be aware that we were not quite of our own making and yet did not seem to be simply rewarmed 'tovers of our elders, either. How could I, who back there at barely thirteen realized that I must struggle awake every morning of my fife before anyone else in the house to wrest myself from the grip of my tenacious dreams, be the offspring of a man who slept solidly as a railroad tie? And Damon, fists-up Damon, how could he derive from our peaceable mother? Ready or not, we were being introduced to ourselves, sometimes in a fashion as hard to follow as our father's reading finger. Almost any day in the way stations of childhood we passed back and forth between, prairie homestead and country school, was apt to turn into a fresh puzzle piece of life. Something I find true even yet.

It is Toby, though, large-eyed prairie child that he was, whom I sensed most as I slowed there at the small old school with its common room and the bank of windows away from its weather side. Damon or I perhaps can be imagined taking our knocks from fate and putting ourselves back into approximately what we seemed shaped to be, if we had started off on some other ground of life than that of Marias Coulee. But Toby was breath and bone of this place, and later today when I must go into Great Falls to give the county superintendents, rural teachers, and school boards of Montana's fifty-six counties my edict, I know it will be their Tobys, their schoolchildren produced of this soil and the mad valors of homesteaders such as Oliver Milliron, that they will plead for.

T

HE NEWS OF OUR HOUSEKEEPER-TO-BE GALLOPED TO SCHOOL

with us that next morning, or rather, charged ahead of Damon and me in the form of Toby excitedly whacking his heels against the sides of his put-upon little mare, Queenie.

"I bet she'll have false teeth, old Mrs. Minneapolis will," Damon announced as we rode. "Bet you a black arrowhead she does." Before I could say anything he spat in his right hand, thrust it toward me, and invoked "Spitbath shake," the most binding kind there was.

I was not ready to stake anything on this housekeeper matter. "You know Father doesn't like for us to bet."

Damon just grinned.

"Let's get a move on," I told him, "before Toby laps us."

As soon as we topped the long gumbo hill at our end of the coulee, the other horseback contingents of schoolchildren loped or lolled into view from their customary directions, each family cluster as identifiable to us as ourselves in a looking-glass. Toby by racing ahead had caught up to a dilemma. Should he go tearing off to as many troupes of schoolcomers as he could reach, or

make straight for the schoolhouse and crow our news to the whole school at once?

He settled for the Pronovosts, the newcomers who joined us every morning at the section-line gate.

"Izzy! Gabe! Everybody!" That general salutation was to Inez, riding double behind Isidor. She was in Toby's grade and sweet on him, an entangling alliance he did not quite know what to do with. "Guess what?"

Whatever capacity for conjecture existed in the three minimally washed faces turned our way, it surely did not stretch to the notion of domestic help. The Pronovosts were project people, although the distinction between those and drylanders such as us was shrinking fast. Father already was spending less time on farming and more on hauling wares from the Westwater railhead to the irrigation project camp nearest us, the one called the Big Ditch; the father of the Pronovosts drove workhorses on the gigantic diversion canal under construction there, that breed of old-time earth-moving teamster called a dirt skinner. Not just by coincidence, the Pronovost kids were skinny as greyhoundsâa family their size living in a construction camp tent was never going to be overfed.