The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide (7 page)

Read The Washington Manual Internship Survival Guide Online

Authors: Thomas M. de Fer,Eric Knoche,Gina Larossa,Heather Sateia

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine

• Facilitating medically necessary procedures

• Preventing disoriented patients from wandering or falling

•

Written orders for restraints must include the following:

• Type of restraint and site (e.g., soft limb restraints on upper extremities, mittens)

• Start and end times

• Frequency of monitoring and reevaluation

•

The medical reason for restraint use must be clearly documented in the chart. Patients should be reevaluated at least every 24 hours and orders renewed if necessary.

•

If possible, consider the use of bedside sitters, bed alarms, veil beds, low beds, floor mats, etc., instead of physical restraints. Likewise, chemical restraints (e.g., antipsychotics and low-dose benzodiazepines) should be used only when clearly indicated. Most hospitals have written policies regarding the use of restraints—be sure your orders and documentation comply with hospital policies.

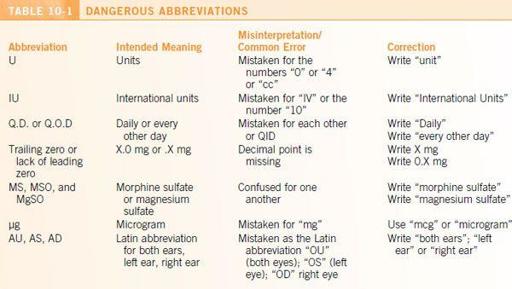

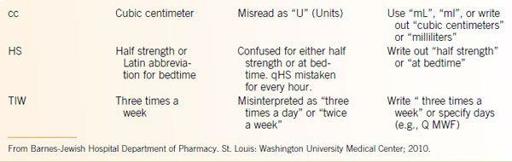

Dangerous Abbreviations for Order Writing

Each hospital may have its own list of unacceptable or dangerous abbreviations.

Table 10-1

shows some of the most common ones.

Daily Assessments

11

ROUNDS

Many programs categorize rounds into prerounds, work rounds, and attending rounds.

Prerounding

•

Prerounding is primarily an intern’s responsibility.

•

Usually allow 30 minutes to an hour before rounds, depending on the number of patients on your service.

•

The exact responsibilities should be worked out individually with your resident.

•

It is often not necessary to physically see all of your patients before work rounds. However, it is customary to see those patients with an acute problem.

•

The most important tasks for prerounding are getting sign-out and catching up on the overnight events (i.e., cross-cover problems). The following example is a good general prerounding plan:

1.

Get your sign-out from the night float or cross-cover team. You need to be aware of any major events that happened overnight, this will dictate how you will spend your time prerounding. Check charted vital signs on all your patients. It is also helpful to check nursing and event notes on the computer.

2.

Check lab results and final results of tests (i.e., CXR, echo). Check telemetry every day on all your monitored patients.

3.

See the patients. A quick check on your patients (2 to 3 minutes per patient) allows you to see how they look and if they have developed any new problems overnight. Of course, patients with more acute illness require more time.

4.

For patients with private physicians, it is often helpful to discuss the plan face-to-face with them in the morning

(i.e., try to catch them on their morning rounds). This saves you time in trying to reach them at their offices or in deciphering their progress notes.

DAILY NOTES AND EVALUATION

•

Interns are primarily responsible for writing daily notes on each of their patients. The SOAP format is usually used for daily notes:

•

S

ubjective: Events over the past 24 hours garnered from the patient, cross-covering physician, or nursing staff.

•

O

bjective: Factual information, vitals, PE, lab results, lines, and tubes. Include microbiology results, X-rays, and other studies here. Always check final official readings of tests.

•

A

ssessment/

P

lan: This is the most important part of the note. It is usually categorized by problem or organ system in the order of importance. Remember to include problems such as electrolyte abnormalities, hypovolemia/hypervolemia, and nutritional status in your problem list and document code status in every note. Also include the type of IV access the patient has and the plan for DVT prophylaxis. In addition, the last category or problem should be discharge planning. Include status and goals (e.g., social work arranging placement, home oxygen).

•

Active medications are often listed in a side column. This exercise can be tedious but ensures that every medication is reviewed daily. Also include the number of days each antibiotic has been given and the expected total duration. Similar documentation can be used with other medications that require loading doses or are tapered.

•

Review the following items daily:

• Do IV lines need to be changed?

• Can IV meds be changed to PO?

• Can you discontinue the Foley?

• Do restraint orders need to be renewed?

• Can you advance the diet and increase the activity of the patient? Is the patient moving his or her bowels? Is there any procedure or test planned that requires that patient to be NPO?

• PT/OT and social work: Are they involved, and should they be? What is the status of discharge planning?

• Are all meds adjusted for renal or hepatic failure?

•

Daily orders should be consolidated and written as early as possible. Don’t forget to order a.m. labs for the next morning (only if they are truly indicated).

Every lab test and study ordered needs to be followed up

. If a study needs to be done stat or ASAP, you must notify the ward clerk and nurse directly and consider talking to the radiologist directly. It is helpful to discuss a brief plan with the patient and the nursing staff. This helps them to be part of the team and also helps move things along.

SIGN-OUTS

Background

•

The initiation of work-hour regulations in 2003 increased the number of physician-to-physician transfers.

•

Patients cared for by a team other than their primary team are at a higher risk for adverse events. Poor sign-out processes can lead to inefficiencies, delays in care, cost increases, and harm.

1

Negative outcomes can be mitigated by formal sign-out systems.

•

Complex systems fail unless communication can be standardized. Atul Gawande, MD, demonstrates that a standardized checklist decreased the rate of major complications by 36%, deaths by 47%, and infections by nearly 50%.

2

Necessary Information for Effective Sign-Out

•

Using a standardized format for each patient will make it easy to ensure all necessary information is included in the written sign-out.

•

This checklist was adapted by Barnes-Jewish Hospital interns from a study at three major centers that compiled focus group information from residents on what is required for effective cross-cover.

3

Administrative Data

•

Patient name, DOB, medical record or hospital number, location, admission date

•

Code status

•

Access

•

Acuity (i.e. sick)

Background Data

•

Brief HPI (1 to 2 lines).

•

Admitting diagnosis/major problem, interventions tried (successful, unsuccessful).

•

Other significant problems, interventions tried (successful, unsuccessful).

•

Significant events of the day.

•

Antibiotic dates (if applicable).

•

Trends.

•

Goals of care/of the hospitalization.

Cross-Cover

•

Anticipatory guidance with specific if–then statements.

•

Specific tests ordered that will come back during the coverage period.

Verbal Communication

•

Face-to-face communication between outgoing and oncoming care providers.

•

Verbally discuss each patient, tailoring conversation to acuity and complexity of the situation.

•

Preferably sign-out should occur in a designated location that can allow the two, or more, physicians caring for the patients to be fully engaged in the process with minimal distraction.

DISCHARGE PLANNING

•

Discharge (D/C) planning must be addressed and readdressed constantly. Proper D/C planning prevents large censuses and results in a more manageable workload for the resident and intern. D/C planning should start on admission.

•

Social work should be consulted on admission if D/C needs are anticipated (assisted living, placement, transportation). Scheduled meetings with case coordinators or social workers are often helpful to reassess the situation and provide updates.

REFERENCES

1

.

Horwitz LI, Moin T, Krumholz HM, et al. Consequences of inadequate resident sign-out for patient care.

Arch Intern Med.

2008;168:1755-1760.

2

.

Gawande A.

The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right

. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, LLC; 2009.

3

.

Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, et al. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign out.

J Hosp Med.

2006;1:257-266.

Discharges

12

•

With proper planning, discharges can be smooth for you and the patient.

•

In today’s health-care system many more diseases are being managed and followed in the outpatient setting. Therefore, it is critical that the patient has follow-up and has a completely reconciled medication list. In addition, the patient’s physician must be aware of any pending issues, studies, or laboratory draws scheduled prior to outpatient follow-up. Communication with all involved parties is crucial to a successful discharge process and ultimately prevents many “bounce backs.”

•

Significant reimbursement disincentives will soon go into effect for those with MI, CHF, and pneumonia and who are readmitted within 30 days (for any reason!). Other diagnoses are likely to follow.

DISCHARGE PROCESS/PEARLS

•

Obtain social work/case coordinator assistance early in the admission. Try to anticipate issues and problems early on (e.g., transportation, home oxygen, home antibiotics, or nursing/rehabilitation facility placement).

•

Make sure the patient and his or her family are aware of possible discharge dates

so they can arrange their schedules and not be caught off guard.

•

Arrange for home care services at least 24 hours before discharge

(i.e., home nursing, home laboratory draws, PT, OT).

•

Criteria for home O

2

:

• Pao

2

<55 mm Hg, must be measured within 48 hours of discharge.