The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (20 page)

Read The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 Online

Authors: Margaret MacMillan

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #History, #Military, #World War I, #Europe, #Western

Tirpitz threw himself into the work. He arranged for a group of leading industrialists and businessmen to issue a resolution in support of the naval bill and even managed to obtain a grudging promise of support from Bismarck. He visited Germany’s other rulers; the Grand Duke of Baden for one was completely charmed: ‘such an excellent personality’, he wrote to the German Chancellor, Caprivi, ‘a man whose character and experience are equally splendid’.

78

In Berlin, Tirpitz spent hours chatting genially with selected Reichstag members in his office.

When the Reichstag was in session again in the autumn, the Kaiser, Tirpitz, and Bülow all addressed it, cooing like turtle doves. The bill was merely a defensive measure, said Wilhelm. ‘A policy of adventure is far from our minds,’ added Bülow (although it was in this speech he also mentioned Germany’s place in the sun). ‘Our fleet has the character of a protective fleet,’ Tirpitz claimed. ‘It changes its character not one bit as a result of this law.’ His bill was going to make the Reichstag’s work much easier over the next years by getting rid of the ‘limitless fleet-plans’ of the past.

79

On 26 March 1898, the First Navy Law passed easily by 212 votes to 139. The Kaiser was ecstatic: ‘Truly a powerful man!’ Among other things, Wilhelm revelled in being free of the need to get approval from the Reichstag – and took the credit for himself. As he boasted to the controller of his household in 1907, when yet another Navy Law was passed: ‘He absolutely fooled the members of the Reichstag. They had not the smallest idea, he added, when they passed it, what its consequences would be, for the law really meant that anything he wanted would have to be granted.’ It was, he went on, ‘like a corkscrew with which I can open the bottle any moment I like. Even if the froth spurts to the ceiling, the dogs will have to pay until they are black

in the face. I have now got them in the hollow of my hand, and no power in the world will stop me from drinking the bottle dry.’

80

Tirpitz immediately started work on his next steps. As early as November 1898 he proposed increasing the tempo for building capital ships from the present three per year. A year later, at an audience in September 1899, he told the Kaiser that more ships were an ‘absolute necessity for Germany, without which she will encounter ruin’. Of the four great powers in the world – which he counted as Russia, Germany, the United States and Britain – the last two could be reached only by sea. Therefore sea power was essential. And he reminded the Kaiser about the eternal struggle for power. ‘Salisbury’s speech: the great states become greater and stronger, the small smaller and weaker is also my view.’ Germany must catch up. ‘Naval power is essential if Germany doesn’t want to go under.’ He wanted a new naval bill, before the expiry of the first in 1903, to double the fleet. Germany would then have forty-five ships of the line. True, Britain would have more. ‘But’, he went on, ‘also against England we undoubtedly have good chances through geographical position, military system, torpedo boats, tactical training, planned organizational development, and leadership united by the monarch. Apart from our by no means hopeless conditions of fighting, England will have lost [any] inclination to attack us and will as a result concede to your Majesty sufficient naval presence … for the conduct of a grand policy overseas.’

81

The Kaiser not only agreed completely, he rushed off and announced that there would be a second naval bill at a speech in Hamburg. Tirpitz had to present the bill earlier than he had planned but in fact the timing turned out to be good. The outbreak of the Boer War in October 1899 and the British seizure of steamers off southern Africa at the end of the year inflamed German opinion. The Second Navy Law passed in June 1900 and duly doubled the size of the German navy. Later that year the grateful Kaiser promoted Tirpitz to the rank of vice admiral and expunged his middle-class background by ennobling him and his family. The future looked clear for Germany to continue through the ‘danger zone’ towards its rightful position in the world.

Yet to achieve this triumph, the German government was going to pay a high price. It had bought the support of the important agrarian interests in the German Conservative Party, the DKP, by promising a

tariff to keep out cheap Russian grain and in 1902, it duly brought in a protective measure. The loss of an important market further antagonised the Russians, already annoyed by Germany’s seizure of Kiachow Bay in China and by German moves into the Ottoman Empire. German public opinion against Britain and in favour of a big navy had been useful but once stirred up it was not easy to calm it down again. Most importantly of all the British, both decision-makers and the public, had started to take notice. ‘If they could just sit still in Germany’, Hatzfeldt, the German ambassador in London, complained, ‘then the time would come soon when fried pigeons would fly into our mouths. But these continuous hysterical up- and down-turns of Wilhelm II and the adventurous navy policy of Mr von Tirpitz will lure us on to destruction.’

82

Tirpitz made three crucial assumptions: that the British would not notice that Germany was developing a big navy; that Britain would not and could not respond by outbuilding Germany (among other things, Tirpitz assumed that the British could not afford a big increase in their naval budget); and that, while being pressured into making friends with Germany, Britain would not decide to look for friends elsewhere. He was wrong about all three.

CHAPTER 5

Dreadnought

: The Anglo-German Naval Rivalry

In August 1902 another great naval review took place at Spithead in the sheltered waters between Britain’s great south coast port of Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight, this time to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII. Because he had suddenly come down with appendicitis earlier in the summer, the coronation itself and all festivities surrounding it had been postponed. As a result most of the ships from foreign navies (except those of Britain’s new ally Japan) as well as those from the overseas squadrons of the British navy had been obliged to leave. The resulting smaller review was, nevertheless,

The Times

said proudly, a potent display of Britain’s naval might. The ships displayed at Spit-head were all in active service and all from the fleets already in place to guard Britain’s home waters. ‘The display may be less magnificent than the wonderful manifestation of our sea-power witnessed in the same waters five years ago. But it will demonstrate no less plainly what that power is, to those who remember that we have a larger number of ships in commission on foreign stations now than we had then, and that we have not moved a single ship from Reserve.’ ‘Some of our rivals’,

The Times

warned, ‘have worked with feverish activity in the interval, and they are steadily increasing their efforts.’ They should know that Britain

remained vigilant and on guard, and prepared to spend whatever funds were necessary to maintain its sovereignty of the seas.

1

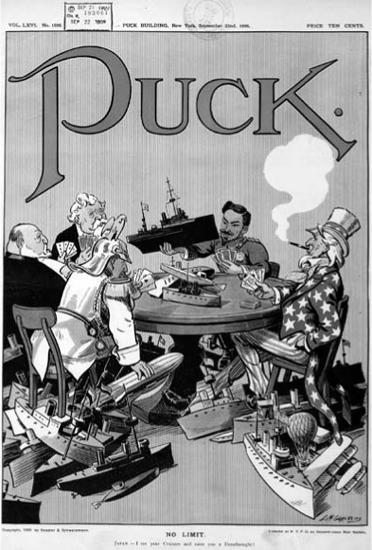

5. In the years before 1914 European countries engaged in an increasingly intense and expensive arms race on land and at sea. New and improved technologies brought faster and stronger battleships including the mighty dreadnoughts. Here Wilhelm II, his uncle Edward VII and President Emile Loubet play their high stakes power while the rising powers of Japan and the United States start to join in.

Although

The Times

did not name Britain’s rivals, there can have been little doubt in its readers’ minds that Germany was rapidly coming to take the foremost place among them. While the British still counted France and Russia as potential enemies, opinion, among both the ruling elites and the general public, was increasingly worried about their neighbour on the North Sea. In 1896 a best-selling pamphlet, ‘Made in Germany’, by the journalist E. E. Williams painted an ominous picture: ‘A gigantic commercial State is arising to menace our prosperity, and contend with us for the trade of the world.’

2

Look around your own houses, he urged his readers. ‘The toys, and the dolls, and the fairy books

which your children maltreat in the nursery are made in Germany: nay, the material of your favourite (patriotic) newspaper had the same birthplace as like as not.’ From the china ornaments to the poker for the fire, most of the furnishings were probably made in Germany. And it got worse still: ‘At midnight your wife comes home from an opera which was made in Germany, has been here enacted by singers and conductor and players made in Germany, with the aid of instruments and sheets of music made in Germany.’

3

A new factor was making itself felt in Europe’s politics and its international relations: public opinion, which was to put unprecedented pressures on Europe’s leaders and limit their freedom of action. As a result of the spread of democracy and the new mass communications as well as greatly increased literacy, publics were not only better informed but also felt more connected to each other and to their nations. (We face our own revolution in the way we gain information and relate to the world with the internet and the growth of social media.) In the world before 1914, railways, telegraph lines and then telephones and radios transmitted domestic and international news at unprecedented speed. The foreign correspondent became a respectable professional and, increasingly, newspapers preferred to use their own nationals rather than rely on locals. Russians, Americans, Germans or Britons could read about their nation’s most recent disasters or triumphs at their breakfast tables – and develop their own views which they could make known to their governments. Some, especially in the old ruling elites, deplored the change. ‘Small, closed circles of courtly and diplomatic individuals’ no longer managed international relations, said the head of the German Foreign Office’s press section. ‘The public opinion of the nations has acquired a degree of influence on political decisions previously unimaginable.’

4

The fact that there was a German press bureau showed how governments understood that, for their part, they needed to manipulate and use public opinion at home and abroad by controlling the information they fed journalists, placing pressure on newspaper proprietors to take a favourable line or by outright bribery. The German government tried to buy support in the British press but since it could only afford to subsidise a small and unimportant paper its efforts served to do little but make the British even more suspicious of Germany.

5

In 1897 Lord Northcliffe’s mass circulation

Daily Mail

ran a series

which urged its readers ‘for the next ten years fix your eyes very hard on Germany’. The German menace, pride in Britain, appeals to patriotism, demands for a stronger navy, these were all to be common themes with the Northcliffe papers (which by 1908 included the

Daily Mirror

and the more elite

Observer

and

Times

)

6

and indeed with others such as the

Daily Express

and the left-wing

Clarion

. Their editors were not so much creating public opinion as telling the public what it wanted to hear but the effect of the press campaigns and the alarmist writings of men such as Williams was to stir up public emotions and elevate patriotism into jingoistic nationalism.

7

Salisbury complained that it was like having ‘a huge lunatic asylum at one’s back’.

8

At the start of the twentieth century, relations between Britain and Germany were worse than they had been at any time since Germany appeared on the map of Europe. The failure of the talks between Chamberlain and the German ambassador in London, the public and private outbursts of the Kaiser, the well-reported anti-British and pro-Boer sentiment among the German public, even the silly controversy over whether Chamberlain had insulted the Prussian army, all left their residue of mistrust and resentments in Britain as well as in Germany. Valentine Chirol, who had been

The Times

’ correspondent in Berlin until 1896, wrote to a friend at the start of 1900: ‘Germany is, in my opinion, more fundamentally hostile than either France or Russia, but she is not ready yet … She looks upon us as upon an artichoke to be pulled to pieces leaf by leaf.’

9

Moreover, British statesmen suspected, with some reason, that Berlin would be happy to see Britain drawn into conflict with France and Russia – and might even do what it could to hurry matters along. In 1898, when France and Britain came close to a war over their competing African claims, Wilhelm claimed that he was like a bystander with a bucket of water at a fire, doing his best to calm things down. Thomas Sanderson, the Permanent Undersecretary at the Foreign Office, commented that the Kaiser was more like someone ‘running about with a lucifer match and scratching it against powder barrels’.

10