The War at the Edge of the World (44 page)

Read The War at the Edge of the World Online

Authors: Ian Ross

The Blue House had been rebuilt on its old foundations, down by the river. Afrodisia was there, and Castus had already paid her several visits. Perhaps he would go there again this evening, with Valens… He smiled at the thought, and felt a warmth in his limbs. For a moment he pictured himself in ten or fifteen years, retiring with honour from the legion, a fat purse of gold in his fist and a grant of land to farm, married to Afrodisia with a crowd of children already growing up around him. The thought pleased him.

No, he thought. Not me. He remembered Marcellina, the envoy’s daughter; he often thought of her, and wondered what had happened to her. Married now, in some distant city. That was the way of civilians, after all: they wanted homes, families, security. But Castus was not a civilian, neither would he ever be.

He recalled the funeral ceremony for Constantius, Eboracum’s last taste of imperial glory. The towering pyre built in the centre of the parade ground, three storeys high and taller than a house, the wood painted to look like marble, decked with garlands and hung with laurel wreaths. The linen-wrapped body of the old emperor had been placed at the top, under a canopy made to look like a temple pediment, and all the units of the army had marched around the pyre with reversed weapons.

Constantine had lit the pyre, of course. When the flames had risen to the top, an eagle had flown from the temple canopy, fluttering for a moment in the light and heat of the fire, the showering sparks, before vanishing into the night sky. The spirit of Constantius, so the orators said, released from his mortal flesh. Rain turned to steam in the heat of the burning pyre, and the massed soldiers had cried out their praises to the old emperor and the new.

Arma virumque cano

… Castus thought.

Arms and the man I sing

… That was by Virgil – the greatest poet of Rome, so Diogenes claimed. Castus saw in his mind the word-symbols scratched onto his wax tablet: the writing exercises that the former schoolteacher made him perform during their secret tuition sessions. Just the simple stuff, Castus had told him. After all, even quite stupid people could read and write, so why should he not? He only needed enough skill to read a strength report or a watchword tablet, but the teacher insisted on starting with Virgil. Perhaps by spring, he had suggested, Castus would have mastered enough of reading and writing to get through the whole poem. Castus himself doubted that.

And by the spring, things could be different anyway. Already there were rumours, carried by the traders from Gaul, of new wars on the continent. The Franks had crossed the Rhine on plundering raids, and there was displeasure among the other emperors at Constantine’s assumption of the imperial purple. The soldiers had made Constantine – would Constantine need his soldiers again? The tide of history and great events had rolled over Castus and then receded, but still he knew the fierce joy of battle, the longing for action.

But then he thought of that other woman: Cunomagla. The memory of her stirred his blood. He pictured her riding from the fallen fort with her spear in her hand, crying defiance to the soldiers. Rome had harried the north, but not conquered it, and Constantine had not been the only victor of the campaign. If Cunomagla survived, and he was certain that she had, then she would be the ruler, in her son’s name, of whatever still remained of the nations of the Picts. As he marched in under the huge pitted arches of the gatehouse, Castus grinned to himself, though none of his men could see it. It would be a hard kind of ruling, but a noble one. In his heart he saluted her: a queen among her people, at the furthest edge of the world.

~

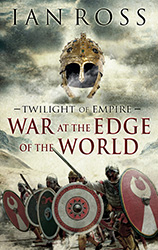

War at the Edge of the World

is the first book in the Twilight of Empire series.

We hope you enjoyed it!

The next gripping instalment in the series will be released in Summer 2015

For more information, click one of the links below:

~

An invitation from the publisher

Compared to the glories of the high empire, the days of Caesar and Augustus, Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, the later Roman world can seem a dark and mysterious place, lit only by the flames of violence and the passions of competing religions. But the early fourth century was an age of great drama, of towering personalities and warfare spanning the known world, a time of revolution when, in the space of a few short decades, the old certainties of the classical era were swept away as Constantine, and his adopted religion of Christianity, reshaped the empire and gave a new definition to much of the future of Europe.

There is a statue of the emperor in York today, outside the minster. A modern piece, it depicts Constantine seated rather pensively, gazing at a broken sword, but it marks the approximate position of the ancient

principia

, the headquarters building of the legionary fortress where he was first acclaimed by the army on 25 July

AD

306. No source records Constantine being raised on a shield, but the practice was apparently established by the time his half-nephew Julian was similarly acclaimed just over half a century later; it was perhaps originally a Germanic custom, and as at least one Germanic king was present in York that day, I have chosen to imagine that the shield ritual began with Constantine himself.

Modern York is a medieval city, on Roman foundations. In this novel I have preferred the Roman name Eboracum, just as I have used the ancient rather than the modern names for other places. I have not been entirely consistent with this: Rome remains Rome, not Roma, and the Rhine and Danube rivers retain their familiar names. My intention was to use the term that best evokes the ancient past, with the fewest modern associations.

Our literary sources for this period are scarce, sometimes contradictory and often partisan: the churchmen Eusebius and Lactantius, eager to glorify their hero Constantine, together with later historians such as Zosimus, Eutropius and Aurelius Victor. Among the few contemporary writings are the series of panegyrics, speeches given in honour of the emperors themselves, and often in their presence, today known as the

Panegyrici Latini

. These are works of imperial propaganda, highly rhetorical and elaborate, but they preserve many details of the era otherwise lost to history.

One of these,

Panegyric VIII

, contains the first recorded mention of the people known as the Picts. Another (

Panegyric VI

) makes one of the few slight references to the campaign conducted in the north of Britain by Constantius, Constantine’s father, shortly before his death in

AD

306. Constantius did not, the orator claims, ‘seek out British trophies, as commonly believed’; for this to need refuting in public, it must have been a rumour widely known. It would not be the first time, after all, and certainly not the last, that a war has been concocted to satisfy the desire for military glory; from that seed this story takes its root.

The Roman army of the early fourth century was in a period of transition. At its core was still the traditional legion of heavy infantry, officially about five to six thousand men strong, divided into ten cohorts, each cohort subdivided into six centuries. But most legions had been split up into several smaller detachments, and those that remained intact were much reduced in strength. The old century, commanded by a centurion and numbering around eighty men, may have shrunk to as little as half that number by the era of Diocletian.

Not only the size of the old legion had changed; the legionaries of the early fourth century also looked quite different from their forefathers. Gone were the familiar segmented iron body armour, short stabbing sword and rectangular shield of the age of Trajan. The tetrarchic soldier wore mail or scale armour, carried an oval shield and a long sword, and wore a long-sleeved tunic, boots and breeches, an appearance perhaps more suggestive of the medieval than the classical world.

Within two or three decades, this ancient military system would be overhauled once more, and a newly structured army rise from its ruins. Much about this process is still unclear, but I have preferred to assign the changes to the reforming Constantine rather than the traditionalist Diocletian.

If the Roman world of this era appears often misty, the lands that lay outside the imperial borders are almost entirely lost in fog. In particular, the north British people known to the Romans as the Picts have long been mysterious, their culture and society, their language, even their existence the subject of much academic and popular debate and controversy. My portrayal of the Picts and their culture in this novel is necessarily speculative, an imaginary hybrid of earlier Roman accounts of the northern Britons and descriptions from the early Middle Ages. I make no claims to veracity; while I have based my fiction on the fragments of fact wherever possible, my intention has been to try and show a society and a people that might plausibly have existed. No historian, I believe, could do more than that.

For a contextualising overview of the period, the relevant chapters of David S. Potter’s

The Roman Empire at Bay:

AD

180–395

(2004) are both erudite and very readable. Bill Leadbetter’s

Galerius and the Will of Diocletian

(2009), while often contentious, covers the complex period between the abdication of Diocletian and the rise of Constantine in considerable detail.

In Praise of Later Roman Emperors

(1994), edited by C. E. V. Nixon and Barbara S. Rodgers, is an invaluable compilation of the full texts and translations of the

Panegyrici Latini

, while Michael H. Dodgeon and Samuel N. C. Lieu’s

The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars,

AD

226–363

(1991) contains the surviving documentary texts on the eastern campaign of

AD

298 and the battle of Oxsa (often mistakenly referred to as the battle of Satala in modern works).

The later Roman military has received increasing study in recent decades. Pat Southern and Karen Dixon’s

The Late Roman Army

(1996), and more academic monographs by Martinus J. Nicasie and Hugh Elton, have been joined by A. D. Lee’s comprehensive

War in Late Antiquity: A Social History

(2007). Ross Cowan’s forthcoming

Roman Legionary:

AD

284–337

, part of the Osprey military history series, will doubtless offer a concise and accessible popular alternative, backed up by the latest research in the field.

Historical works on the Picts are rather more scarce. Nick Aitchison’s

The Picts and the Scots at War

(2003) gathers a wealth of information from a wide range of sources, while James E. Fraser, in

From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795

(2009), gives one interpretation of the possible genesis and development of this elusive people.

Assembling the historical background for this story has taken nearly a decade of research, but without certain people this effort would not have borne fruit. My particular thanks go to my agent, Will Francis at Janklow & Nesbit, for his immediate and effective championing of the novel, and to Rosie de Courcy at Head of Zeus for being so enthusiastic about Castus and his adventures. I am also very grateful to David Breckon, who first read the manuscript, for his insightful and encouraging comments, and to the members of the Roman Army Talk online forum, whose collective knowledge has been a guide and an inspiration to me for many years as I picked my way across the dark terrain of the late Roman world.

War at the Edge of the World

is the epic first instalment in a sequence of novels set at the end of the Roman Empire, during the reign of the Emperor Constantine.

Centurion Aurelius Castus – once a soldier in the elite legions of the Danube – believes that his glory days are over, as he finds himself in the cold, grey wastes of northern Britain, battling to protect an empire in decline.

When the king of the Picts dies in mysterious circumstances, Castus is selected to lead the Roman envoy sent to negotiate with the barbarians beyond Hadrian’s Wall. Here he will face the supreme challenge of command, in a mission riven with bloodshed, treachery and tests of his honour. As he struggles to avert disaster and keep his promise to a woman he has sworn to help, Castus discovers that nothing about this doomed enterprise was ever what it seemed.

‘Hugely enjoyable. The author winds up tension into an explosion of fast-paced events.’

Conn Iggulden

‘Ian Ross blazes into the world of Empire and legions with the verve and panache of an old hand. This is up there with Harry Sidebottom and Ben Kane and is destined for the premier league.’

M.C. Scott

‘An impressive debut… Set in a little-known era of the Roman Empire – the early 4th Century AD – it throws us head first into a chaotic world in which emperors rise and fall, fortunes change and a man does not know who to trust. This is a thumping good read, well-crafted, atmospheric and thoroughly enjoyable. A real page-turner. Where’s the next volume, please?’

Ben Kane