The Vietnam Reader (8 page)

Read The Vietnam Reader Online

Authors: Stewart O'Nan

Late on the third night he wrote to his father, explaining that he’d arrived safely at a large base called Chu Lai, and that he was taking now-or-never training at a place called the Combat Center. If there was time, he wrote, it would be swell to get a letter telling something about how things went on the home front—a nice, unfrightened-sounding phrase, he thought. He also asked his father to look up Chu Lai in a world atlas. “Right now,” he wrote, “I’m a little lost.”

It lasted six days, which he marked off at sunset on a pocket calendar. Not short, he thought, but getting shorter.

He had his hair cut again. He drank Coke, watched the ocean, saw movies at night, learned the smells. The sand smelled of sour milk. The air, so clean near the water, smelled of mildew. He was scared, yes, and confused and lost, and he had no sense of what was expected of him or of what to expect from himself. He was aware of his body. Listening to the instructors talk about the war, he sometimes found himself gazing at his own wrists and legs. He tried not to think. He stayed apart from the other new guys. He ignored their jokes and chatter. He made no friends and learned no names. At night, the big hootch swelling with their sleeping, he closed his eyes and pretended it was not a war. He felt drugged. He plodded through the sand, listened while the NCOs talked about the AO: “Real bad shit,” said the youngest of them, a sallow kid without color in his eyes. “Real

tough shit, real bad. I remember this guy Uhlander. Not such a bad dick, but he made the mistake of thinkin’ it wasn’t so bad. It’s bad. You know what bad is? Bad is evil. Bad is what happened to Uhlander. I don’t wanna scare the bejasus out of you—that’s not what I want—but, shit, you guys are gonna

die.”

2

Early Work

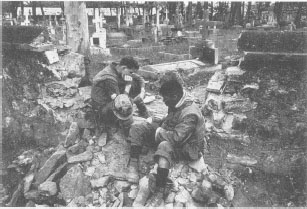

Hue, Vietnam, 1968. Marines play cards on the destroyed wall of a cemetery during the Tet Offensive.

Most of the books that came out during the war were nonfiction and political in nature—anti- or prowar tracts, position papers and studies of the larger forces involved in the region. With the notable exception of

The Green Berets,

nearly all the Vietnam fiction and poetry of note that came out between 1965 and 1973 was antiwar, and most appeared after 1968, when even such an establishment figure as trusted evening newscaster Walter Cronkite conceded on air that the war was unwinnable. As on campus, the climate in serious American literature was staunchly antiwar, with marquee writers like Norman Mailer, Mary McCarthy, and Robert Bly stridendy denouncing first the Johnson and then the Nixon administrations. War supporters John Steinbeck and Jack Kerouac were seen as traitors to their more socially committed roots and reprimanded in print.

Like much of the socially conscious literature of the period, the works in this chapter look at the moral choices individuals make or refuse to make in relation to some larger group (the Army, America as a whole, humanity), questioning individuality and the consequences of conformity To many people, the reality of the war seemed an affront to American political and moral ideals; it seemed un-American. Other opponents of the war noted similarities to earlier U.S. conquests, most often the near-eradication of the Native Americans. It was business as usual, they claimed. In the early work, as in all the work, authors examine claims of American innocence and evil, reaching

back into history for evidence. Home-front America shows up here as well. There’s an attempt to bring the war home, or at least to contrast the daily hardships and brutality of the war with America’s fatuous affluence. Again, the portrayal of the Vietnamese is interesting across these pieces, as is the view of the older generation, though, as usual, the final identification the authors ask the reader to make is with the U.S. soldier, to understand his conflicted position.

Of all the major American novels about Vietnam, David Halberstam’s

one very hot day

(1967) is singular in that it’s the only one with Vietnamese point-of-view characters. Halberstam was a high-profile journalist assigned to the region in the early years of the U.S. buildup and has written insightfully about the war in both fiction and nonfiction.

one very hot day

is written in a plain, realistic style. Like

The Green Berets,

it was picked up by the Book of the Month Club; as of 1998 it’s still in print.

Chapter VII of Tim O’Brien’s

If I Die in a Combat Zone

(1973) brings the green reader into Vietnam in the second person, then switches to “us,” and finally “1” as new guy O’Brien shows us a number of Army personnel and their differing views of Vietnam. The flat, economical Hemingway style only emphasizes how strange and frightening his new surroundings are, and the portraits he draws of his fellow soldiers are decidedly unheroic.

While American poets had been writing antiwar poetry for years, Michael Casey’s

Obscenities

(1972) was the first major collection written by a veteran. It won the 1972 Yale Younger Poets Prize and earned glowing notices in the

New York Times Book Review

and elsewhere. Casey served as an MP along Highway 1 in 1969-70. His work here is plainspoken, lightly ironic, and sneakily deep, and few American writers have so successfully drawn the difficult relationship between American soldiers and the Vietnamese civilians around them.

Vet David Rabe’s play

Sticks and Bones

was first produced by a university theater in 1969, but was later chosen for a major Broadway production in 1971 by the powerful director Joseph Papp. It’s a confrontational piece, extravagant in its effects—including ghosts, onstage violence, absurd humor, and blatantly emblematic characters. The family is patterned after the plastic Nelson family from 1950s TV, and

American denial of the war and protestations of innocence are thoroughly shredded.

On the heels of Michael Casey’s

Obscenities,

small presses across the United States published a number of important collections of veterans’ poetry. Vets Jan Barry and W. D. Ehrhart gathered the finest pieces from these as well as uncollected poems for their anthology

Demilitarized Zones

(1976). Typical of the early period, much of the strongest work in the book examines the difficulty of conveying the experience of the war to an uncaring America.

Authors of the period often responded to that difficulty by trying innovative forms or strategies, breaking away from the realistic or at least showing it in a strange light. In much of the early work, ironic, often disturbing humor provided both a relief and a way of confronting the horrible facts. Authors used the impact of war on the body to prompt a visceral rather than intellectual response, with interesting results. Rabe’s tactic of contrasting the stark terror of the war with plastic popular culture is shocking, whereas O’Brien and Casey use a more subtle, deadpan humor.

While these early works were well received, none was widely read beyond a small intelligensia. It would not be until the mid-seventies, well after the fall of Saigon, that Americans as a whole looked back and rediscovered the war.

one very hot day

D

AVID

H

ALBERSTAM

1967

At eleven thirty they were moving haphazardly along the canal, one of those peaceful moments when earlier fears were forgotten, and when it was almost as if they were in some sort of trance from the heat and the monotony, when they were fired on. Three quick shots came from the left, from the other side of the canal. They appeared to hit short, and they landed near the center of the column, close to where Lieutenant Anderson was. He wheeled toward the bullets, spoke quickly in Vietnamese, taking three men with him and sending a fourth back to tell Thuong what he was doing—not to send anyone unless it was clearly a real fight, and he could hear automatic weapon fire; they were taking no automatic weapons, Anderson said.

He sensed that it was not an ambush; you trip an ambush with a full volley of automatic weapons fire—to get the maximum surprise firepower and effect, you don’t trip it with a few shots from an M-l rifle; the fact that the sniper had fired so quickly, Anderson thought, meant that there was probably one man alone who wanted to seem like more than one man. But damn it, he thought, you never really know here, you tried to think like them and you were bound to get in trouble: you thought of the obvious and they did the unique. He brought his squad to the canal bank, and two more bullets snapped near them.

Ping, snap. Ping, snap.

He told one of the Viets to go above him on the canal bank, and one to stay below him, and one to stay behind him as he waded the

canal. They were to cover him as he crossed, and they were not to cross themselves until he was on the other side; he didn’t want all four of them bogged down in mid-canal when they found out there was an automatic weapon on the other side. They nodded to him. Do you understand me, he asked in Vietnamese. He turned to one of them and asked him to repeat the instructions. Surprisingly the Vietnamese repeated the instructions accurately.

“The Lieutenant swims?” the Viet added.

“The Lieutenant thinks he swims,” Anderson said, and added, “do you swim?”

The man answered: “We will all find out.”

Anderson waited for a third burst of fire, and when it came, closer this time, he moved quickly to the canal bank and into the water, sinking more than waist high immediately. As he moved he kept looking for the sniper’s hiding place; so far he could not tell where the bullets were coming from. He sensed the general direction of the sniper, but couldn’t judge exactly where the sniper was. He was all alone in the water, moving slowly, his legs struggling with the weight of the water and the suck of the filth below him. He knew he was a good target, and he was frightened; he moved slowly, as in a slow-motion dream; he remembered one of the things they had said of the VC in their last briefings. (“The VC infantryman is tenacious and will die in position and believes fanatically in the ideology because he has been brainwashed all his life since infancy, but he is a bad shot, yes, gentlemen, he is not a good shot, and the snipers are generally weak, because you see, men, they need glasses. The enemy doesn’t get to have glasses. The Communists can’t afford ’em, and our medical people have checked them out and have come up with studies which show that because of their diet, because their diet doesn’t have as much meat and protein, their eyes are weak, and they don’t get glasses, so they are below us as snipers. Brave, gentlemen, but nearsighted, remember that.”) He remembered it and hoped it was true.

Ahead of him all he could see was brush and trees. Remember, he thought, he may be up in the trees: it was another one of the briefings: “Vietcong often take up positions in the tops of trees, just like the

Japanese did, and you must smell them out. Remember what I’m telling you, it may save your life. You will be walking along in the jungle, hot and dirty. And you hear a sniper, and because your big fat feet are on the ground, you think that sniper’s feet are on the ground too. But you’re wrong, he’s sitting up there in the third story, measuring the size of your head, counting your squad, and ready to ruin your headgear. They like the jungle, and what’s in the jungle? Trees. Lots of ’em. Remember it, gentlemen, smell them in the trees.”

Anderson had left the briefing thinking all Vietcong were in the trees; even now as he walked, he kept his eye on the trees more than on the ground.

Behind him he heard the Viets firing now, but there was still no fire from the sniper. He reached the middle of the canal where the water was deepest; only part of his neck, his head, and his arms and weapons were above water now. He struggled forward until he reached the far side of the canal. He signaled to the Viets to hold fire, and then, holding his weapon in one hand (he did not want to lay it on the canal bank, suppose someone reached out from behind a bush and grabbed it), he rolled himself up on the canal edge, but there was still no fire. He punched through the first curtain of brush, frightened because he did not know what would be there (Raulston had once done this, pushed through and found to his surprise a Vietcong a few feet away; they had looked at each other in total surprise, and the Vietcong had suddenly turned and fled—though Beaupre in retelling the story claimed that it was Raulston who had fled, that the Vietcong had lost face by letting him escape, had lied to his superiors, and that Raulston was now listed on Vietcong rolls as having been killed in action, and that Raulston was now safe because they didn’t dare kill him again).

He moved past the canal and into the dense brush, found what looked like a good position, and fired off a clip to the left, right in front of him, most of the clip to his right, and finally, for the benefit of his instructors, for Fort Benning, the last one into a tree nest. Nothing happened and he reloaded and moved forward. Then there were two little pings, still in front of him, though sounding, perhaps it was his imagination, further away. But the enemy was there, and so, encouraged,

he began to move forward again, his senses telling him that the sniper was slightly to his right. He was alone, he had kept the others back at the canal bank; they would be no help here, for they would surely follow right behind him and he would be in more trouble for the noise they would make and for being accidentally shot from behind, that great danger of single-file patrolling; yet going like this, he sensed terribly how alone he was—he was in

their

jungle, they could see him, know of him, they could see things he couldn’t see, there might be more of them. He moved forward a few yards, going slowly both by choice and necessity in the heavy brush. If there had been a clock on the ground, where he left the canal and entered the jungle, it would have been six o’clock, and he was now moving slowly toward one o’clock. He kept moving, firing steadily now. From time to time he reversed his field of fire. Suddenly there was a ping, landing near him, the sound closer, but coming from the left, from about eleven o’clock. The shot sounded closer, and more excited and frightened now, he moved quickly in that direction, feeling the brush scratch his arms and his face (he couldn’t use his hands to protect his face, they were on his weapon); now he squeezed off another clip, two quick ones, three quick ones, the last three spaced out, a musical scale really.