The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (9 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

Worse than these situations were the locks caused by accidents, usually a fallen horse. Max Schlesinger watched the combined efforts of two policemen, ‘a

posse

of idle cabmen and sporting amateurs, and a couple of ragged

urchins’ needed to get one horse back on its feet. Frequently the fallen horse was beyond help, and licensed slaughterhouses kept carts ready to dash out, deliver the

coup de grâce

and remove the animal’s body. People, too, were often badly injured, or killed, in these locks and on the streets more generally: between three and four deaths a week was average. More commonly, though, Schlesinger observed, ‘Some madcap of a boy attempts the perilous passage from one side of the street to the other; he jumps over carts, creeps under the bellies of horses, and, in spite of the manifold dangers...gains the opposite pavements.’ It took a foreigner to notice this, for hundreds of boys earned their livings by spending hours every day actually in the streets: the crossing-sweepers.

One of Dickens’ most compelling characters is Jo, the crossing-sweeper in

Bleak House

, who lives in a fictional slum called Tom-all-Alone’s, which has been variously sited. An accompanying illustration shows the Wren church of St Andrew’s, Holborn (destroyed in 1941 in the Blitz); but there are suggestions in the novel itself that it might be located in the slum behind Drury Lane, or even in St Giles. These seem to be more likely, as Jo eats his breakfast on the steps of the nearby Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

26

before taking up his post at his crossing ‘among the mud and wheels, the horses, whips, and umbrellas’.

Jo and his kind were necessary. In the rain even a major artery ‘resembled a by-street in Venice, with a canal of mud...flowing through it. And as often as [the crossing-sweeper] swept a passage, the bulwarks of mud rolled slowly over it again until they met.’ The crossing-sweepers were performing an essential service, confining the mud to the sides of the roads, clearing away the dung, the refuse and the licky mac, making a central route for people to cross. All day, every day, this was the task of the old, the infirm and the young, all coatless, hatless and barefoot. Most busy corners had a regular sweeper, who held his position as of right; he was known by sight and even by name to many who passed daily, as the mysterious Nemo in

Bleak House

knows Jo. Residents relied on their sweeper to run errands and do small chores, and in turn gave him cast-off clothes or food.

27

There were also morning-sweepers who stood at the dirtiest sections of the main roads, sometimes half a dozen or more over a mile, to sweep for the benefit of the rows of clerks walking into work, enabling them to arrive at their offices with clean boots and trousers. By ten o’clock the morning-sweepers had dispersed, going to other jobs. Sweepers were often approved by the police, either outright – sometimes sweepers checked at the local stations before they took up a pitch – or if the local beat-constable saw a sweeper was honest and helpful, he made sure that he kept his pitch, seeing off rivals for a good corner. Some large companies paid a boy or elderly man to act as their own sweeper, both to ensure that their clerks arrived looking respectable as well as to provide the same service for their customers.

Apart from these individuals, there were also civic attempts to keep the roads clean. A Parliamentary Select Committee in the 1840s recorded that three cartloads of ‘dirt’, almost all of it animal manure, were swept up daily between Piccadilly Circus and Oxford Circus alone – 20,000 tons of dung annually in less than half a mile. In addition to this, every day more refuse was cleared, most of which had fallen from the open carts constantly trundling by: coal dust, ash, sand, grit, vegetable matter, all ground to dust by the horses’ hooves and the carts’ iron wheels. In wet weather, it was shovelled to the sides of the roads before being loaded on to carts by scavengers employed by the parishes, with the busiest, most traffic-laden streets cleared first, before the shops opened, when traffic made the task more difficult. Dustmen also appeared on every street, ringing a bell to warn householders to close their windows as they drew near. Traditionally they wore fantail hats, which resembled American baseball caps worn backwards, with a greatly enlarged leather or cloth bill, the back flap protecting their

necks and shoulders. Wearing short white jackets and, early in the century, brown breeches or, later, like Sloppy in

Our Mutual Friend

, red or brown cotton trousers, they carried huge wicker baskets and a ladder that allowed them to climb up the side of their carts and deposit their loads.

28

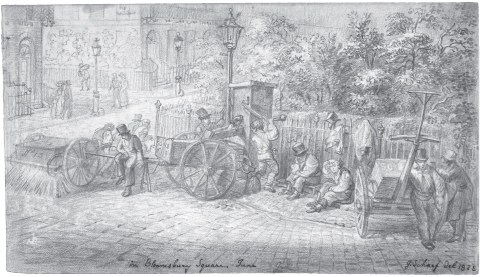

(See Plate 1, where fantail, red trousers and bell are all shown.)

There were attempts throughout the period to mechanize the street-cleaning process. In 1837, a footman named William Tayler, who lived in Marylebone, wrote in his diary: ‘saw a new machine for scrapeing the roads and streets. It’s a very long kind of how [sic]...One man draws it from one side of the street to the other, taking a whole sweep of mud with him at once...There are two wheels, so, by pressing on the handles, he can wheel the thing back everytime he goes across the street for a hoefull.’ By 1850, the streets were ‘swept every morning before sunrise, by a machine with a revolving broom which whisks the dirt into a kind of scuttle or trough’.

With so many unpaved roads, and as many poorly paved ones, dust was as much a problem in dry weather as mud was in wet. When David Copperfield walked from the Borough, in south London, all the way to Dover, he arrived ‘From head to foot...powdered almost...white with chalk and dust’. Because all the roads surrounding London were as dusty in hot weather, when heading for the Derby, ‘Every gentleman had put on a green veil’ while the women ‘covered themselves up with net’: ‘The brims and crowns of hats were smothered with dust, as if nutmegs had been grated over them’; and without the veils the dust combined with the men’s hair-grease, turning it ‘to a kind of paint’. Street dust also spoilt the clothes of pedestrians, and could even insinuate itself indoors, damaging shopkeepers’ stock and furniture in private households.

Water not only kept down the dust in dry weather but also helped prolong the life of macadam surfaces, so by the end of the 1820s most parishes maintained one or more water carts, filled from pumps at street corners. The pumps were over six feet high, with great spouts that swung out over the wooden water troughs on the carts.

29

By the 1850s, the rumbling of ‘tank-like watering-carts’ marked the arrival of spring as they rolled out across the city. When the driver pressed a lever with his foot, it opened a valve in the water trough, and the water squirted out of a perforated pipe at the back of his cart as he slowly drove along, ‘playing their hundred threads of water upon a dusty roadway’.

That is, he drove along if driving were possible. Traffic was not the only problem. For much of the century, London was one large building site. On a street-by-street basis, the creation of the infrastructure of modernity meant that the roads were constantly being dug up and relaid, sometimes for paving but more often for what we would call utilities, but then didn’t even have a name.

Responsibility for street lighting, originally a private matter, had devolved over the centuries to the parishes and finally to the civic body. In the early

1700s, parish rates were used to pay for a tallow light to be lit in front of every tenth building between 6 p.m. and midnight, from Michaelmas to Lady Day (29 September to 25 March). But these created little more than an ambient glow, and the more prosperous called on what was, in effect, mobile lighting: linkmen who carried burning pitch torches and who, for a fee, lit the way for individual pedestrians. Even this was not ideal. By the late eighteenth century the poet and playwright John Gay expressed a common fear:

Though thou art tempted by the link-man’s call,

Yet trust him not along the lonely wall;

In the mid-way he’ll quench the flaming brand,

And share the booty with the pilf’ring band.

In the same vein a print from 1819 (Plate 6) shows three linkboys, where the one on the right is picking a pocket. Gay therefore recommended, ‘keep [to] the public streets, where oily rays, / Shoot from the crystal lamp, o’erspread the ways’. These ‘oily rays’ were oil lamps, which, in winter and when there was no full moon, householders hung on the front of their buildings, to be tended by a parish-paid lamplighter. Even when the number of lamps in the City had risen five-fold, the amount of light they gave depended, as

The Pickwick Papers

recorded, on ‘the violence of the wind’. And when the lamps were alight, grumbled Louis Simond, the West End streets were nothing more than ‘two long lines of little brightish dots, indicative of light’.

But change was coming, and quickly. In 1805, Frederick Winsor demonstrated a new method of lighting, fuelled by gas, outside Carlton House – the residence of the Prince of Wales, later the Prince Regent – between Pall Mall and St James’s Park (at what later became the south end of Regent Street).

30

For the birthday of George II he created a display of coloured

gas-burners, including four shaped like the Prince of Wales feathers, and an illuminated motto. (For more on illuminations, see pp. 363–9.) By 1807, thirteen lamp-posts had been erected along Pall Mall, with three gaslights in each, for a three-month experiment. Awed visitors filled the street every night to gaze at the sight of one gas lamp-post giving more light than twenty oil lamps. The caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson drew a cartoon of the wondering citizens (Plate 5): a comic foreigner overcome by the marvels of modernity in London, a preacher who warns of ignoring religion’s ‘inward light’ in favour of this outward show, and a prostitute worrying that, with no dark corners left, ‘We may as well shut up shop.’ (Her customer shares her concern.)

Whitbread’s brewery in the City, which had installed its own gas plant in the same year as Winsor’s first exhibition, offered to light part of nearby Golden Lane and Beech Street. These eleven lamps gave a light ‘so great that the single row of lamps fully illuminate both sides of the lane’ – which is a telling insight into the feebleness of oil lamps, unable to shed their light across a narrow passage. By 1812, there was gas lighting in Parliament Square and four of the surrounding streets, and in 1813 Westminster Bridge was lit by gas. These new lights also made it possible to establish more firmly the separation between pedestrians and wheeled transport: ‘it has been proposed...[that] to mark the distinction between the two pavements, lamps should be placed on stone pedestals.’ (Iron was substituted for stone for practicality, so the pipes could be accessed.)

In the days of oil, the lamplighters filled their small barrels at oilmen’s shops before hoisting them on their backs and, carrying a small ladder and a jug (to transfer the oil from barrel to lamp), jogging swiftly along to complete their route in the brief period between dusk and darkness, then doing the same in reverse to extinguish the lamps in the mornings. To light each lamp they placed their ladders against the iron arms of the lamp-posts, ran up, lifted off the top, which for convenience’s sake they temporarily balanced on their heads, trimmed the wick with a pair of scissors they carried in their aprons, refilled the reservoir, lit the wick, replaced the top and ran on to the next post. With the arrival of gas the job became easier. No longer was it necessary to carry heavy oil barrels, nor to refill each lamp;

instead they just ran up their ladders, turned a stopcock and lit the gas with their own lamp.

Central London and the main routes in and out of the city swiftly became brightly lit: by the 1820s, 40,000 gas lamps were spread over 200 miles of road. As early as 1823, the Revd Nathaniel Wheaton described arriving in London by stagecoach from Hammersmith to Kensington, ‘all the way for miles brilliant with gas-light’. But the brightness was confined to the capital. The stage before Hammersmith was Turnham Green, where ‘we could neither see nor feel any thing but pavements’ – it was still entirely unlit. And in the late 1830s, the sexual predator Walter roamed the roads ‘between London and our suburb’ on the western side of the city, perhaps Isleworth. As the roads there were ‘only lighted feebly by oil-lamps’, prostitutes frequented ‘the darkest parts, or they used to walk there with those who met them where the roads were lighter’.

31

The new technology, however, came at the price of long-term civic discomfort. The

Oxford English Dictionary

dates the first use of the term the roads being ‘up’ – to mean the road surface having been removed for work to be carried out – to 1894, but as early as the 1850s Sala wrote that in his private opinion the paving commissioners enjoyed repeatedly taking the ‘street up’. When the gas mains were laid in Parliament Square, sewer pipes were also renewed, and the water companies took the opportunity to exchange their antique wooden pipes for iron – for MPs, at least, everything

was done at once. For most of the population it was a different matter. In the thriving south London suburb of Camberwell, the first gas company was established in 1831; three years later, twenty miles of street had been torn up to receive new mains. Over the next two decades, competition between the local gas companies meant that ‘occasionally as many as ten sets of pipes would be laid in one street’. This became a chronic problem. In 1846, Fleet Street was closed for five weeks for repaving, the previous road having been partially destroyed when a new sewer was laid; immediately afterwards the road was once more reduced to single file while first gas mains and then water pipes were replaced. Until 1855, each parish looked after its own streets, or, even worse, this was the responsibility of each district within a parish, sometimes with different commissions to deal with paving, lighting, water and soon telegraph too, so roads were endlessly being taken up and resurfaced. In 1858, 150 shopworkers and residents of the Strand petitioned the London Gasworks company, complaining that the entire street had been closed to traffic at the peak season. They also noted, bitterly, ‘the short hours at which the men have for the most part worked’ and the poor quality of the resurfacing once they had finished.