The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (62 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

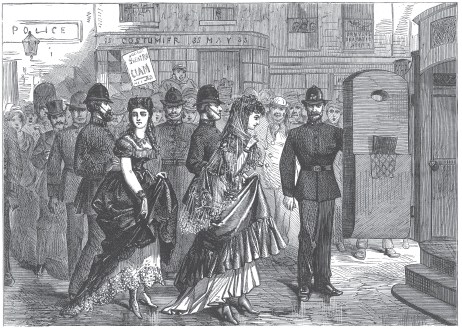

The two men initially seemed not to take the prosecution seriously. On his first court appearance Boulton wore ‘a cherry-coloured evening dress rimmed with white lace’ together with a wig giving him a demure chignon, while Park’s gown was ‘dark green satin...low-necked, trimmed in black lace’, and covered by a shawl; he wore his hair in flaxen curls. (Both disappointed their followers by afterwards dressing as men and, apparently on legal advice, sporting moustaches and whiskers.) There was no public outrage: the crowds waiting by the police vans waved their hats and shouted encouragement; when the men’s letters were read out in court, ‘the audience in the body of the court appeared to be exceedingly amused’. There was little

sense that Boulton and Park were in any way a public danger or disgrace: this was just one more instance of street theatre. It shows a substantial shift in attitudes from 1835, when in his ‘Visit to Newgate’ in

Sketches by Boz

, Dickens reported on seeing the last two men to be executed for ‘unnatural acts’, or homosexual, consensual sex. They were unnamed by Dickens but have since been identified as John Smith and John Pratt. At the time, ‘the nature of [their] offence rendered it necessary to separate them’ from the prison’s other convicted men.

The assumption in literature, and in all good books, was that women who transgressed the moral code by becoming sex-workers were sure to meet an untimely death. Flora Tristan was certain that ‘Many die in hospitals from shameful diseases’, or in neglect and poverty ‘in their frightful hovels’. Dr Ryan wrote that up to 10 per cent of these women killed themselves, ‘or become insane, or idiotic’ through moral turpitude. William Tait agreed that prostitutes fell into a decline and rapidly died: this was a ‘general law’. Acton, in contradiction, compiled figures to show that prostitutes did not commit suicide more often than any other group, but fiction supported the views of his colleagues. In

London by Night

, the barmaid Louisa, who was ‘Lost’ on entering the Argyle Rooms, was ‘Found’ at the end of the story, when her body was pulled from the river, where she had ended her life.

The Romantic notion of suicide was that it respresented the act of a rash and impetuous free (male) spirit. While few young men may have killed themselves for love, as Romantic literature had it, it was the case then, as now, that far more men than women committed suicide – up to four times as many. Despite these statistics, between the end of the eighteenth century and the coming of Victoria, there was a perceptual shift. From the late 1830s it was thought that it was women who killed themselves more frequently, and that they did so for love. This change is illustrated in the series of engravings of an eighteenth-century pond, known as Rosamond’s Pond, in St James’s Park, which was filled in in 1770. In 1780, an etching of it in its former state was captioned: ‘This spot was often the receptacle of many unhappy Persons, who in the stillness of an Evening Plung’d themselves into Eternity.’ In 1825, the etching was reissued and the caption altered:

‘The South West corner of St. James’s Park was enriched with this romantic scene...

its melancholy situation seems to have tempted more persons, (especially young women) to suicide by drowning than any other place about town.

’ In 1859, Sala claimed that Rosamond’s Pond had been the Waterloo Bridge of its day, for it was there that ‘forsaken women’ went to drown themselves.

For, a mere dozen years after Waterloo Bridge opened, it had become a byword for suicides. A political essay as early as 1829 used the bridge as an obvious synonym for suicide without feeling the need for any explanation: ‘The man who loves his country with a sincere affection, unwilling to witness the decline of her prosperity and glory, already hesitates only between pistols and prussic acid, Waterloo-bridge and a running noose.’ In a short story in the late 1830s, Dickens had a drunkard end his life on the bridge. By then, however, it was generally women abandoned by their lovers who were said to kill themselves there: the bridge was known as ‘the English “Bridge of Sighs”...“Lover’s Leap”, the “Arch of Suicide”...a favourite spot for love assignations; and a still more favourite spot for the worn and the weary, who long to cast off the load of existence...To many a poor girl the assignation over one arch...is but a prelude to a fatal leap from another.’

Thomas Hood added a link to prostitution in his poem, ‘The Bridge of Sighs’ (1844), basing his story on a real incident, when Mary Furley, an impoverished seamstress faced with the workhouse, threw herself into the Regent’s Canal, taking one of her two small children with her. Hood’s poem altered the location to Waterloo and removed all the identifying details. Much later, Dickens described the death of a woman in the Regent’s Canal that was probably much closer to reality. Walking at dusk through Regent’s Park ‘one day in the hard winter of 1861’, he saw a cab driver speaking to the park keeper with ‘great agitation’, before rushing off, followed by the novelist. ‘When I came to the right-hand Canal Bridge, near the cross-path to Chalk Farm, the Hansom was stationary, the horse was smoking hot’, and, lying ‘on the towing-path with her face turned up towards us, [was] a woman, dead a day or two, and under thirty, as I guessed, poorly dressed in black. The feet were lightly crossed at the ankles, and the dark hair, all pushed back from the face, as though that had been the last action of her desperate hands, streamed over the ground.’

That was journalism. In fiction it was the river rather than the canal that called to Dickens in his depictions of desperate prostitutes. In

Oliver Twist

, Nancy gestures to the Thames: ‘How many times do you read of such as me who spring into the tide...It may be years hence, or it may be only months, but I shall come to that at last.’ (Although compared to the end Dickens gave her, bludgeoned to death by Sikes, drowning might have been more merciful.) In

David Copperfield

, Martha, who had grown up in the small town of Great Yarmouth, flees to London to hide her shame after she ‘falls’. David comes across her at Blackfriars Bridge and follows her along the river, past Waterloo Bridge, past Westminster Abbey, to Millbank – that is, along the streets frequented by prostitutes, through the slum around Westminster,

and then back to the river, where she cries: ‘I know I belong to it. I know that it’s the natural company of such as I am!’ These prostitutes flit across London’s bridges like the ghosts they would soon become. In

Little Dorrit

, begun five years later, in 1855, Little Dorrit and Maggie, her simple-minded companion, walk across London Bridge at night, where they meet a prostitute walking east, in the direction of Granby Street and Waterloo Road. Maggie asks her, ‘What are you doing with yourself?’ and the answer is stark: ‘Killing myself.’ This may be metaphorical, a conventional view of the natural destination of one who leads her life, or it may be literal. We don’t know, as she vanishes into the morning mist.

Other locations for suicide were equally symbolic. A particular magnet for the desperate was the Monument to the Great Fire of London, a stone column 202 feet high topped by an urn in the shape of flames, standing 202 feet from the spot where the fire that devastated the City in 1666 first broke out. In low-rise, nineteenth-century London, the Monument was far more visible than it is today and was one of the most important sights of the City; many visitors climbed its 300-plus stairs for the view of London spreading beneath them. Yet negative connotations were ever-present. In

Barnaby Rudge

, set in the 1780s, a young man is sent off for a day in London with 6d to spend on ‘diversions’, and his father recommends passing the entire day at the top of the Monument: ‘There’s no temptation there, sir – no drink – no young women – no bad characters.’ By the time Dickens wrote this, in 1841, the main temptation that people associated with the Monument was jumping over the edge, and this father, who is not a loving one, may be telling his son that he might kill himself for all he cared.

Even so, few chose it for this purpose. In 1788, a baker jumped off, followed in 1810 by a diamond merchant and, shortly afterwards, another baker. In 1839, a fifteen-year-old boy, thought to have lost his job, leapt from the platform, as did a baker’s daughter. As a result, a guard was stationed at the top, but he failed to prevent Jane Cooper, a servant, throwing herself over. After her death a cage was placed around the platform, to prevent any others from following suit. Six people had plunged to their deaths here in forty-four years, four of whom were men, but it was still said that suicide by women crossed in love was ‘a tradition of the Monument’.

But it was the river, always the river, to which Dickens returned. In 1860, his journalistic narrator stood at the riverside at Wapping, ‘looking down at some dark locks in some dirty water’, said to be the local ‘Bridge of Sighs’. He comments to an ‘apparition’ that materializes beside him, ‘A common place for suicide,’ and the chilling answer is: ‘Sue...And Poll. Likewise Emily. And Nancy. And Jane...Ketches off their bonnets or shorls, takes a run, and headers down here, they doos. Always a headerin’ down here, they is. Like one o’clock.’ The journalist conscientiously asks, ‘And at about that hour of the morning, I suppose?’ The apparition rejects this: ‘They an’t partickler. Two ’ull do for them. Three. All times o’ night.’ The poor, the hungry, the desperate: none was particular, just looking for an end.

At the beginning of the century, in 1801, the essayist Charles Lamb refused an invitation to the Lake District, unable to bear leaving behind ‘all the bustle and wickedness round about Covent Garden, the very women of the Town, the Watchmen, drunken scenes, rattles, – life awake, if you awake, at all hours of the night, the impossibility of being dull in Fleet Street, the crowds, the very dirt & mud, the Sun shining upon houses and pavements, the print shops, the old book stalls...coffee houses, steams of soup from kitchens, the pantomimes, London itself a pantomime and a masquerade, – all these things work themselves into my mind and feed me...I often shed tears in the motley Strand from fulness of joy at so much Life.’ Yet many others saw not life but death in what Arthur Clennam in

Little Dorrit

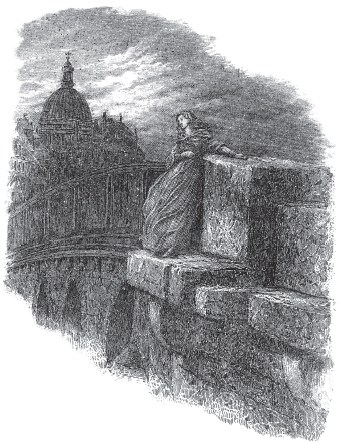

described as London’s ‘streets, streets, streets’. In Henry Wallis’s

The Death of Chatterton

(1859), one of the most famous paintings of the nineteenth century, the main area of the picture is given to the image of the young poet who has committed suicide. Behind him, through the window, can be seen the dome of St Paul’s, the symbol of the indifferent, anonymous city that has crushed him, and continues on, uncaring. This is what Dickens meant when he wrote, ‘with how little notice, good, bad, or indifferent, a man may live and die in London...his existence...[is] a matter of interest to no one save himself; he cannot be said to be forgotten when he dies, for no one remembered him when he was alive.’

Yet in the same year that Dickens stood by that Wapping bridge,

looking down into the water where so many women had met their end, he also created a fictional barrister who had chambers in Gray’s Inn Square, precisely where the young Dickens himself had begun his writing life. The barrister, a dried-up man of fifty-five, fretted: ‘What is a man to do? London is so small!...Then, the monotony of all the streets, streets, streets – and of all the roads, roads, roads – and the dust, dust, dust!’ He gives his watch to a man who has chambers near by, asking him to look after it while he is out of town. And that is the last anyone sees of him until, after ‘his letter-box became choked’, the porter enters his rooms to find that he had hanged himself. Leaving London and leaving life were one and the same.