The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (44 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

In the daytime, there was a wider range of choices. There were taverns, public houses, eating houses, chophouses, ham-and-beef shops, alamode beef houses, oyster rooms, soup houses, pastry-cooks, cookshops and coffee houses. Some of these places overlapped in terms of what, and whom, they served, but most had a distinct profile. What is perhaps noticeably absent from this list is the restaurant, which did not emerge on the London eating scene until the 1860s. The

Oxford English Dictionary

lists several usages before this date, but they all refer either to restaurants in Europe or compare English establishments with their European counterparts. Sala, for example, mentions the Haymarket ‘restaurants’ only to dismiss them as places where they give you things ‘with French names’. Although initially all of these eating places seem not to be part of street life, their separation from the street was far more ambiguous than their names suggest.

Most closely linked to street life were the pastry-cooks and the cookshops. Pastry-cooks supplied not just pastry but a variety of cooked dishes. When David Copperfield gives his first dinner party, the roast chicken, stewed beef, vegetables, cooked kidneys, sweet tart and jelly all come from the pastry-cook. Twenty years later, Dickens listed a similar range of food in an essay on how the day visitor in London managed to feed himself. (If it was a ‘herself’ who needed feeding, it was even more difficult.) In a pastry-cook’s window, Dickens’ visitor sees two old turtle-shells with ‘SOUPS’ painted on them, a dried-up sample meal spread out for display, and a box of stale or damaged cut-price pastry on a stool by the door. The welcome, warned Dickens, would be as glum and dispiriting as the display: every pastry-cook employed ‘a young lady…whose gloomy haughtiness…announced a deep-seated grievance against society’. A couple of years later a guidebook was more positive, recommending pastry-cooks for ‘a good cup of tea and

a chop’, adding that ‘for a light meal, when you have a lady with you, there are several admirably conducted houses’.

Cookshops, or bakeshops, although they often carried the same foodstuffs as the pastry-cooks, were regarded as places for the working classes, because earlier in the century they were where the working classes, without access to kitchen ranges or even kitchens, took their food to be cooked in a communal oven.

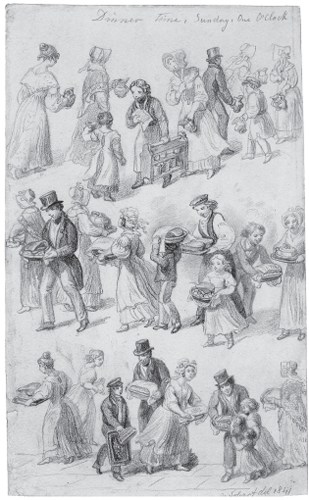

98

For a Sunday dinner, the housewife had an earthenware dish divided into two unequal parts; on one side she piled potatoes, with ‘the modest joint’ on top; into the other she poured the pudding batter before carrying it all to the cookshop in the early morning and collecting it a few hours later. Thomas Wright, the working-class engineer, disapproved of cookshops: the ‘meat [is] burnt to a cinder outside, and red raw inside; and pies [have] scorched crusts and uncooked insides’, not to mention the fact that the joints were returned with ‘the marks of slicing’, as part of the meat had been shaved off by the cookshop owners, or ‘the print of the knife that has been used in lifting the tops of the pies, in order to toll the inside’. Happy were the artisans’ families who did not need to resort to the cookshop, but they were few and far between. Cookshops did their best business on Sundays, and on Christmas Day Dickens made a habit of going to the ‘shabby genteel’ neighbourhoods of Somers Town and Kentish Town at Christmas to ‘watch…the dinners’ coming and going.

For the rest of the week, and the rest of the year, cookshops sold ready-cooked food, either to be eaten on the premises, or to be taken home. In

Little Dorrit

, there is ‘a dirty shop window in a dirty street, which was made almost opaque by the steam of hot meats, vegetables, and puddings…Within, were a few wooden partitions, behind which [sat] such customers as found it more convenient to take away their dinners in stomachs than in their hands.’ Beef, veal, ham, greens, potatoes and pudding were a typical menu. In Bethnal Green in the 1860s, offal was also available, with cows’ heels and baked sheep’s heads, which a family might eat on Saturday night, as well as food to supply ‘the immediate wants’ of passers-by: the same list of

stodge-heavy offerings of puddings, pastry, pies and saveloys that David Copperfield had enumerated four decades earlier. For the main thing was to stave off the ever-present hunger. One street boy remembered a cookshop by Billingsgate market that specialized in pea soup, ‘exposed most temptingly in a large tank in one of the windows’. The soup cost 3d a basin, or 1d for a half-basin, and the ‘initiate’ chose his day carefully: ‘It was freshly made on Monday, and even then was good. On Tuesday, however, the thick residue at the bottom of the tank remaining unsold was left, and the usual

ingredients…were added to it, making it much richer and more substantial. On Wednesday, this process was repeated, with the result that Wednesday’s soup was a thick pureé [sic] in which a spoon would stand erect.’ Street boys ordering a pennyworth of the Wednesday soup and a halfpenny-worth of bread ‘could go in the strength of that meal for twenty-four hours’.

Coffee shops were of two sorts: those for the working classes and those for City gents. Some working-class coffee shops had a temperance tinge to them; many were used by working men as a meeting place, where communal newspapers could be read and political discussions held. Many workers tried to find a congenial regular spot between their lodgings and work, stopping there every morning instead of going to a coffee stall. It was a little more expensive, but it was warm, and there was a newspaper to read. In the late 1810s, there was one in Bear Street, leading into Leicester Square, where for 6d a month subscribers even had access to magazines. One man set up a coffee house in Greville Street, near Hatton Garden, in 1834; having ambitions for it, he offered his customers in addition to newspapers and magazines ‘several hundred volumes’ and ‘a

conversation room

’. Unfortunately his morals got in the way: refusing to adulterate his tea and coffee to make them go further, which, he said, all coffee houses did, he went bankrupt. (The fact that he was a ‘somewhat notorious’ political radical didn’t help him either.) Most coffee houses, however, did not aspire so high. Pierce Egan, in his novel

Life in London

, described one coffee shop as a haunt of ‘drunkenness, beggary, lewdness, and carelessness’, although this is more likely to be the middle class’s view of poverty than necessarily the prevailing state of affairs. The accompanying picture shows a small room with one candle, wooden tables and benches, and a few stools by the fire. Many people used the coffee shops as somewhere to stay warm. Thirty years after Egan, Sala visited an early-morning coffee shop that before dawn was giving shelter to ‘half a dozen homeless wretches’ who had paid for a single cup of coffee in order to be allowed to sit and doze indoors.

The coffee houses clearly filled a need: from only a few dozen catering to artisans in 1815, they had increased in numbers by 1840 to nearly 2,000; there a full breakfast could be purchased for 3d. A coffee house in one working-class district served up to 900 customers a day, who had

a choice of three rooms: the cheapest was open from 4 a.m. to 10 p.m., where customers could enjoy a breakfast of coffee, bread and butter for 1½d; the second-grade room offered coffee, a penny loaf and a pennyworth of butter for 3d; or, in the most expensive room, customers could order a dinner where the coffee shop supplied the bread and the coffee but the diner brought his own cooked meat. The customer bringing cooked food, or a raw chop or a herring, which the waiter put on the gridiron over the fire, was a routine service. Dickens described one such coffee house near Covent Garden in 1860, watching, enchanted, as ‘a man in a high and long snuff-coloured coat, and shoes, and, to the best of my belief, nothing else but a hat…took out of his hat a large cold meat pudding’. The man was clearly a regular, because as soon as he sat down the waiter brought him tea, bread, and a knife and fork.

99

City coffee houses were of a different order. Some were quasi-hotels, letting out rooms. The Brontës on their first foray to London stayed at the Chapter Coffee-House in Paternoster Row, while the nearby London Coffee House, on the north side of Ludgate Hill, is where the fictional Arthur Clennam lodges in

Little Dorrit

. The mysterious Julius Handford, in

Our Mutual Friend

, lodges at the Exchequer Coffee-House, Palace Yard, in Westminster. These establishments were the meeting places of businessmen,

and their decor matched their customers’ prosperity, with ‘cosy mahogany boxes’ (booths)

100

and sanded floors in dark-panelled rooms always supplied with a vast range of newspapers: the New England Coffee-House had even the New York papers, ‘dated only twenty-one days back: so rapidly had they been transported over 3000 miles of ocean, and 230 of land!’ Specific trades patronized specific coffee houses. The Jerusalem Coffee House in Cowper’s Court, Cornhill, was linked to the East Indies, China and Australia trades; Garraway’s, in Exchange Alley, was linked to the Hudson Bay Company (and in

Martin Chuzzlewit

is called a ‘business coffee-room’). Legal London had its own coffee houses around the Inns of Court and Holborn. George’s was across from the new Royal Courts of Justice as well as near the solicitors clustered around Lincoln’s Inn. John’s Coffee-house, in a lane by the gatehouse of Gray’s Inn, is where David Copperfield goes to look for his old friend Tommy Traddles. He gives the waiter Traddles’ name and, because it is a legal haunt, the waiter knows off the top of his head which chambers Traddles is in, even though he is not particularly successful.

For the West End men, there were also cigar divans, usually behind or above a cigar shop. A 1s fee obtained a cigar and a cup of coffee, plus access to a comfortable room furnished like a drawing room, with magazines and books. Mr Simpson, before he opened a restaurant in the West End, owned a cigar divan on the Strand, considered ‘one of the most attractive, and by far the most comfortable lounge in the metropolis’. By the 1850s, there was also Gliddon’s Divan, next to Evans’s Supper Rooms (see p. 358), which was ‘conducted in the most gentlemanly style’; Follit’s Old-Established Cigar Stores, near Portman Square; and the Argyle Divan, on Piccadilly. This last opened after the theatres closed, which gives a hint that the divans were not entirely respectable. In Trollope’s 1855 novel,

The Warden

, Mr Harding, a clergyman from the country, tries to avoid his acquaintances and ends up in a cigar divan; the reader is intended to relish the incongruity of an unworldly cleric in such a place.

The divans were financially well out of reach of most men. For those with less disposable income, particularly in the City, even lunch was a snatched meal. Edmund Yates said that in the 1840s he and his fellow junior clerks at the main post office were given a quarter of an hour to eat. In smaller offices the younger men ‘merely skat[ed] out…for a few minutes…for a snack’, while the married clerks brought bread and cheese from home or, as Reginald Wilfer does in

Our Mutual Friend

, got in a penny loaf and milk from a dairy to eat in the counting house. The most junior employees ‘eat whatever they can get, and wherever they can get it, very frequently getting nothing at all’.

The ‘impecunious juniors’ from the post office went to Ball’s Alamode Beef House, in Butcher Hall Lane (demolished together with Newgate), which sold ‘a most delicious “portion” of stewed beef done up in a sticky, coagulated, glutinous gravy of surpassing richness’, the same dish David Copperfield had chosen for his treat. Other alamode houses offered boiled beef with carrots, suet dumplings and potatoes: more cheap fillers. For these clerks were not much different from David Copperfield and the small boys buying pea soup: they were all trying to stave off hunger as cheaply as possible, and the alamode and boiled-beef houses catered to this need. In the 1820s, the Boiled-Beef House by the Old Bailey was already famous (its owner, later a theatre leaseholder, has come down to history as ‘Boiled-Beef Williams’). By the 1860s, it was almost the definition of an alamode house, being ‘on a much larger scale’ than any others, apart from one near the Haymarket, on Rupert Street. Choice was limited, the waiters asking, ‘

Which

would you please to have, gentleman,

buttock

or

flank

, or a plate of

both

?’ At lesser houses, the question was even briefer: ‘a sixpenny’ or a ‘fourpenny’?

Soup houses were one step down the scale. In the window, basins, often blue-and-white, were displayed. Depending on the location of the soup house and the size of the portion, 2d or 3d would buy a bowl of soup, some potatoes and a slice of bread. Friedrich von Raumer strayed into a soup house in Drury Lane in 1835. The sign in the window said ‘Soup’, but he assumed that, while this was the speciality, other dishes would undoubtedly be served. He was rapidly disillusioned by both menu and decor: ‘No

table-cloth…[only] an oil-cloth; pewter spoons, and two-pronged forks; tin saltcellar and pepper-box’. For 3d he received a piece of bread, ‘two gigantic potatoes’ and ‘a large portion of black Laconian broth’ with some submerged items he dubiously identified as ‘something like meat’.