The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (35 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

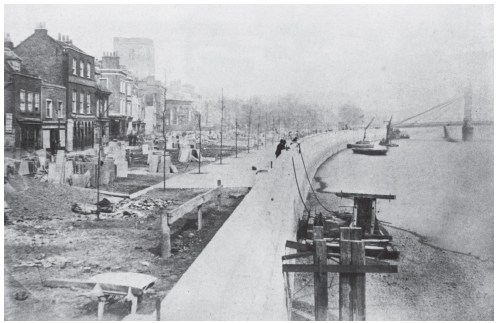

The idea of embanking the river, building out into the Thames to create additional shore, was not new: the Adelphi Terrace to the west of Waterloo Bridge, and Somerset House to the east, had both built on embankments in the eighteenth century. Waterloo Bridge in the early nineteenth century had banked in the area underneath the new span to link up these two pieces of land. There were also embankments where the Temple gardens stood;

76

by Blackfriars Bridge, created in 1769, when the bridge was built; and at Chelsea Hospital, the remains of an older, failed embankment. The new Houses of Parliament, which were built between 1837 and 1852, had created an 850-foot embankment, its buildings jutting out into what had previously been the river. So the new Embankment was new only in scale; the entire length of the river, running for five miles, on the north side of the river from Chelsea to Blackfriars, was embanked. On the south side the land by Lambeth was embanked to prevent the regular floods that the low-lying south bank had always been subject to, creating the reclaimed land on which St Thomas’s Hospital was built.

For many Londoners, the building of the Embankment was an ordeal to be survived. The city had become the site of what was in effect a military campaign, in which ‘a series of fortifications, mostly surmounted by huge scaffolds...arose in our chief thoroughfares’. Arthur Munby felt the full

force of this campaign. He lived in Fig Tree Court, Inner Temple, and the buildings on the south side of his courtyard were all demolished for the work, as he noted dismally in his diary:

APRIL 1864: ‘On my way home, went to look at the great mound of earth, now an acre in extent, which carts are outpouring...at the foot of Norfolk Street, for the Embankment.’

MAY 1864: The embankment seen from Middle Temple garden is now ‘outlined by the scaffold beams and dredging engines ranged far out in the river opposite’.

SEPTEMBER 1864: ‘The embankment grown a more horrible chaos than ever.’

And so it went on for him, year by dreary year:

APRIL 1866: ‘The walls of the Embankment begin to appear: piles for new bridges block up the Thames everywhere.’

Unlike Munby, Dickens did not live by the river, and so he saw less the devastation of the present than hope for the future. In 1861, he wrote, ‘I thought I would walk on by Mill Bank, to see the river. I walked straight on

for three miles

on a splendid broad esplanade overhanging the Thames...When I was a rower on that river it was all broken ground and ditch, with here and there a public-house or two, an old mill, and a tall chimney. I had never seen it in any stage of transition.’

Finally, in 1869, the Embankment opened, and even Munby was awed:

January 1869: ‘The bright morning sun shone on the broad bright river, and the white walls of the Embankment, which stretch away in a noble curve to Westminster, under the dark contrasting masses of the bridges. There is silence, except for the tread of passersby; there is life and movement, almost noiseless, on the water...What a change from the vulgar riot of the Strand! Here is stateliness and quiet, and beauty of form and colour.’

Today the gardens that covered much of the reclaimed land are gone, or are cut off by a four-lane road of whizzing cars, somehow becoming invisible. One historian suggests that this is because we view the Embankment from the wrong viewpoint: it was designed by people who still thought the entrance to London was by water, whereas we approach it from land. This part of London would benefit from a return to stateliness, quiet, and beauty of form and colour.

PART THREE

Enjoying Life

1867: The Regent’s Park Skating Disaster

I

n the

Pickwick Papers

, Sam Weller and the fat boy ‘cut out a slide’ on the ice, and ‘all’ go sliding – Wardle, Pickwick, Sam, Winkle, Bob Sawyer, the fat boy and Snodgrass. Mr Pickwick in particular slides over and over, enjoying himself enormously. But when ‘The sport was at its height...a sharp smart crack was heard. There was a quick rush towards the bank, and a wild scream from the ladies’ – who are not skating, but watching admiringly – as ‘A large mass of ice disappeared, the water bubbled over it, Mr Pickwick’s hat, gloves, and handkerchief were floating on the surface, and this was all of Mr Pickwick that anybody could see.’ This being a comic novel, nothing worse happens than Mr Pickwick getting a ducking and rushing indoors for a hot bath and his bed to ward off a cold.

And that too was how the vast numbers of men who skated regularly on the frozen waters of the London parks regarded the hazards, although this was hardly a risk-free pastime. On one day in 1844 over 5,000 people were counted on the Serpentine, even after ‘the icemen of the Royal Humane Society’ had warned that the ice was dangerously thin; another 2,500 were counted on Long Water, the area north of the Serpentine Bridge, while 1,500 skated on the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens. The Humane Society, established for ‘the recovery of persons apparently drowned or dead’, had set up its first receiving house in 1794 beside the Serpentine, where bathers were taken in summer, skaters in winter. In that one afternoon, by four o’clock the ice had broken under at least ten people on the Serpentine. At St James’s Park, the iceman working for the Humane Society went to the aid of seven or eight skaters who went through the ice there, saving five, while another fifteen got a ducking at the Buckingham Palace end of the water.

The risks slowed few down. In 1855, at St James’s Park, ‘the Express Train came off’: between 300 and 400 men formed a line, each holding on to the coat of the man in front, starting off with ‘some whistling the railway

overture, and others making a noise resembling the blowing off of the steam of a locomotive’. Some of the Foot Guards joined in and soon they ‘glided over the ice at the rate of three-quarters of a mile per minute’. In Regent’s Park, ‘hundreds’ of men skated along the canal tunnel between Aberdeen Place and Maida Hill, racing through ‘in imitation of express trains, with appropriate noises and whistlings’. One weekend there were so many wanting to go through the tunnel that the police barred the entrance; but the next day ‘the trains’ were permitted to go through the tunnel ‘as usual’.

On 6 January 1867, the Serpentine’s ice ‘was about three inches thick, and, with the exception of a small portion at the eastern end, perfectly safe’. A large number of skaters were out, and only five people went through the ice, of whom four were not seriously hurt; the final man ‘was rescued after considerable difficulty’ and put into a warm bath in the Humane Society’s receiving house. St James’s Park, by contrast, warned its skaters of the ‘irregular’ ice, and ‘several immersions’ needed the Humane Society’s assistance. Other parks reported no problems: Kensington Gardens, Clapham Park, Hampstead Ponds ‘and the London, Chatham, and Dover Railway Company’s ponds at Brixton’ were all ‘crowded with sliders and skaters. Several accidents occurred, but not of a serious nature.’

The same could not be said of Regent’s Park. The lake in the park was partially fed by the Tyburn, and there were dangerous currents. Between three and four o’clock a man, possibly employed by the Humane Society, told one spectator the ice was ‘in a very unsafe condition, and that there would be a terrible accident very soon’; she watched as park employees broke up the ice by the Long Island. After the event no one knew why this had been done: an iceman from the Humane Society said he had done so because ‘It has been done ever since I was a boy.’ The park superintendent claimed that the ice was being broken only by the islands, to protect the vegetation and the birds, and no one, he said, had ever suggested it was dangerous. This was contradicted by the Secretary to the Humane Society, who replied that it was very clearly dangerous. The Society’s men had asked the police to keep people away, but were told they had no such powers: it might have been dangerous to go on the ice, but it was not illegal.

The ice was ‘tessellated’, cracked in squares a yard or more across, with

water oozing up between the cracks. Suddenly, near the island, the water abruptly rose up in ‘spurts’. This prompted a sudden rush as everyone headed for the banks, but many were cut off by the quickly cracking surface. Ladders were pushed out along the ice, but some people fell off and disappeared through the ice. Panic ensued, as ‘they skated back towards the centre of the ice, and as they did so they fell, and the whole surface suddenly gave way, and all of them went into the water’.

A huge sheet of ice had broken off, plunging about 250 people into the lake, with hundreds more scrambling to safety. The water, dropping away to the natural bed of the river, was up to twelve feet deep in places and without a firm bottom. Some who were tipped off the ice became trapped underneath. Others lay flat on the surface, clinging to isolated pieces of ice, screaming for help, as the thousand or so spectators on the banks began to scream too. The ten Humane Society icemen did their best. They had ‘the usual appliances’: ropes, wicker ice-boats, a sledge, ladders, drags, boathooks, ice axes and cork belts. But the ice was not firm enough for the Humane Society’s sledges to be launched; the boats were blocked by the large chunks of floating ice; the ropes that were thrown out saved some, but others snapped. And all the while, women and girls stood on the shore, watching as their husbands, sons and brothers, dressed in sodden, woollen, three-piece suits and overcoats, held on to smaller and smaller pieces of ice, finally letting go and sinking, frozen, as the fragments disintegrated. Several men onshore grabbed ropes and jumped in, attempting to rescue their children, brothers or fathers, or complete strangers.

In January, darkness falls by four o’clock, and although flares were lit and placed around the water, it was too dark to continue the search, which had to be given up for the night. By this time nearly 200 men and boys had managed to reach the shore, or were dragged out by hooks and ropes before they drowned, or died of cold. Two surgeons were regularly on call near by for the Humane Society. More doctors and surgeons from the surrounding area rushed to the spot and, in makeshift premises, in the Humane Society’s receiving house and on the open ground, they worked to revive those who had been pulled from the water, while bodies beyond rescue were carried past.

None of those who died in the water that afternoon had any identification on them whatsoever. Almost every one of them was in their teens or twenties; five were children and only two were older men. The bodies were all taken to the nearby Marylebone Workhouse, where they were laid out for relatives and friends to identify. Small objects that might help – a hat with the maker’s name, a letter beginning ‘Dear Richard’ – were placed beside them.

Shirley Brooks, a journalist, and later editor of

Punch

, who lived in Kent Terrace, in the ring of houses surrounding the park, wrote in his diary: