The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (27 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

The reality of nineteenth-century poverty, however, was such that many things had value that today we cannot imagine buying, selling or even giving away. Near the basin where glasses were washed in pubs was a ‘saveall’, a small ledge of pierced pewter-work, in which the dregs from the glasses were deposited, to be sold to ‘the poorer customers’ or (as an afterthought), ‘given away in charity’. In

Dombey and Son

a woman attempts to snatch Florence Dombey on the street, to steal her clothes for resale. Dickens may have read of a case that occurred in 1843, three years before

Dombey and Son

began to appear. A woman applied to a workhouse for relief. The workhouse surgeon thought the three-year-old boy with her was in some way ‘superior’. So puzzling did the child appear that he was, ultimately, interviewed by the Lord Mayor in his home, where the toddler recognized a piano and a watch-guard, notably middle-class objects. He said he had one mother in the country who was kind to him and called him Henry, as well as this woman, whom he called his strawyard mother (a strawyard was a night refuge for the indigent; see pp. 198–9), who had taken away his clothes, which he itemized, and which were the clothes worn by

middle-class children.

53

This was the oddest, but not the only, instance of children being stolen for their clothes. Many workhouses marked even their ugly clothes: in the 1840s, the Camberwell Workhouse had ‘Camberwell parish’ and ‘Stop It’ painted across their uniforms, while lodging houses sometimes had ‘

STOP THIEF!

’ marked on their sheets. There were many incidents that indicated the poor’s utter desperation. Children broke windows or street lights to get themselves arrested: in gaol, they would be warm and fed, and could sleep indoors. In 1868, when a man was sentenced to seven days’ prison for breaking lights, he begged for fourteen, ‘but the magistrate was inflexible’: seven was all he would give him.

Since it was far more comfortable for many to believe in Egan’s rich beggars, the conditions in workhouses grew worse and worse. In 1842, a Select Committee heard from a man who had applied for relief and was punished for his temerity by being confined for forty-eight hours with five others ‘in a miserable dungeon called the Refractory-room, or Black-hole’, a room with no windows. ‘The weather then (August) being exceedingly warm...they complained...and...as a punishment, a board was nailed over the small air-hole.’

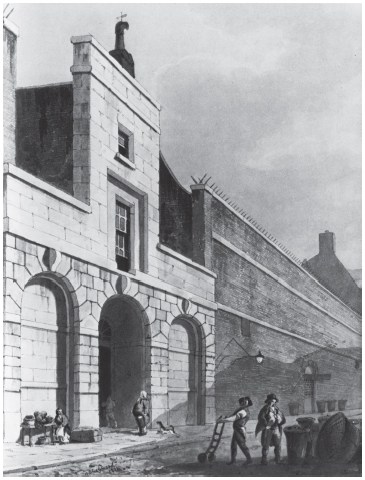

There was little difference between the workhouses and the prisons. There was no sense that prisons were places that should be tucked away: they were physically as well as mentally integrated into the fabric of London. Tothill prison, in what is today Victoria (it was demolished in 1854 to build Westminster Cathedral), was visible from fashionable Piccadilly, where it could be mistaken for a wing of Buckingham Palace, while from Belgravia it looked as if it were set in ‘a very enviable grove of trees’. The Fleet prison, by the nineteenth century almost entirely used for debtors, even had a street number posted on the front entrance: those who did not want to admit to being incarcerated could have their letters sent to 9 Fleet Market and hope that the sender would be none the wiser.

In 1800, there were nineteen prisons in London, which by 1820 had increased to twenty-one, and they were regarded, by those outside the walls, as just one more of the city’s many sights. In

Great Expectations

, when Pip arrives from the country: ‘I saw the great black dome of Saint Paul’s bulging at me from behind a grim stone building which a bystander said was Newgate Prison.’ While he declines to purchase a seat at a trial, one of the gaol’s officials nevertheless shows him the gallows, the whipping post and ‘the Debtors’ Door, out of which culprits came to be hanged’. Sightseers gained entrance easily. In 1843, the splendidly named American

visitor Thurlow Weed sent in his card to the governor at Newgate and was immediately given a tour around the entire prison.

54

In the list of ‘Exhibitions, Amusements, &c.’ in

Routledge’s Popular Guide to London

, Newgate prison is listed after the National Portrait Gallery and before the ‘Polygraphic Hall (Entertainment by Mr. W. S. Woodin)’. In the mainstream

Illustrated London News

, a regular feature entitled ‘Public Improvements of the Metropolis’ highlighted buildings of which a new and modern city should be proud: the Sun Fire-Office’s office was one, Pentonville prison another. There was no difference in the magazine’s attitude, both being considered as bringing the benefits of modernity.

Convict prisons remain with us, but debtors’ prisons vanished in the nineteenth century. For much of the first half of the century, however, those who could not pay what they owed were imprisoned until their debts were met. When the debtor’s creditors decided that they had no option but the law, a writ of execution was put in and the debtor was arrested. He or she was usually first taken to a sponging house (sometimes spunging house), so-called for its ability to squeeze money out of debtors, ‘where, like a spunge, they soon begin, you / Find, to suck out whatever you’ve got in you!’ There the debtor was held under the supervision of the bailiffs while, with luck, he might come to an arrangement with his creditors. These houses were commercial propositions run by private individuals, and living costs were charged just as they were in regular lodgings. According to one novel a small room cost 5s a day, while another claimed a fire was an additional 5s. Dickens priced the more luxurious front drawing room at ‘a couple of guineas a day’. To survive decently as a debtor, one had to have money.

One of the best-known houses was Abraham Sloman’s, at 4 Cursitor Street, off Chancery Lane. In Disraeli’s novel

Henrietta Temple

, published in 1837, it was described as ‘a large but gloomy dwelling’, providing ‘a Hebrew Bible and the Racing Calendar’ for the ‘literary amusement’ of its inhabitants. In Thackeray’s

Vanity Fair

(1847–8), Colonel Crawley is a regular

visitor, passing through at least three times; his ‘old bed’, when he returns, has just been vacated by a captain of the Dragoons, whose mother left him to languish there for a fortnight before paying off his creditors, ‘jest to punish him’. Dickens knew Sloman’s in reality, not simply in literature. In 1834, three years before Disraeli’s novel, John Dickens was arrested yet again for debt, and was taken to Sloman’s to wait for his journalist son, now gainfully employed, to extricate him; that same son re-created the house the following year, as Solomon Jacob’s, also on Cursitor Street, in one of his earliest short stories, ‘A Passage in the Life of Mr Watkins Tottle’, as well as, two decades later, more touchingly as Coavinses’ Castle, in

Bleak House

.

If no one came forward to pay what the debtors owed, the prisoners were taken from the sponging house to a debtors’ prison, where they were kept until the debts were paid – potentially for ever if the debtor had no means of settling. Like Mr Dorrit in

Little Dorrit

, a handful of prisoners were unable to untangle their affairs and spent the bulk of their lives in these institutions: when the Fleet closed in 1842, one prisoner had been there since 1814; another, still in the Queen’s Bench prison in 1856, had been arrested for debt in 1812.

55

Although there were nine debtors’ prisons in London at the beginning of the century, the ones we know best today are the Fleet and the Marshalsea, mostly thanks to Dickens’ depictions of Mr Pickwick in the Fleet and Mr Dorrit in the Marshalsea. These two, with King’s Bench, in Southwark, and Whitecross Street, in the City, held most of London’s debtors.

Despite being places for people who were penniless, debtors’ prisons required cash, and rather a lot of it. In the Fleet those who had money to spend lived on one side, where basic services were provided for a fee. In contrast, ‘The poor side of a debtor’s prison is, as its name imports, that in which the most miserable and abject class of debtors are confined.’ Until the 1820s, the latter received the barest minimum of food and were expected

to beg in order to supplement their rations. Dickens described the opening on to the street, where prisoners stood in turns behind a grille, ‘rattl[ing] a money-box, and exclaim[ing] in a mournful voice, “Pray, remember the poor debtors; pray remember the poor debtors.”’ But, Dickens added, ‘Although this custom has [since] been abolished, and the cage is now boarded up, the miserable and destitute condition of these unhappy persons remains the same.’ After that date, each prisoner with funds was charged ‘footing’ on entry, to provide food for the destitute inmates. For a ‘chummage’ fee to the chum-master – the prison officer in charge of lodgings – the prisoner was given a room, which, because of habitual overcrowding, always had at least one occupant already. Good chum-masters ensured that a prosperous debtor was quartered with an indigent one, whereupon the prosperous new arrival paid a weekly fee to the poorer to go and sleep elsewhere. The destitute prisoner in turn paid a portion of that fee to an even poorer prisoner for space in the corner of his cell, leaving a few shillings a week for food and other necessities. For the better-off, turnkeys let out furniture for a further sum. Food was brought into the prison by family members, or ordered from a local eating house for another sum; drink was similarly available. In a parody of university life, prisoners also ‘subscribed’, as ‘collegians’, to the cost of the fire in the taproom and the provision of hot water. As Mr Pickwick discovered very rapidly, ‘money was, in the Fleet, just what money was out of it; that it would instantly procure him almost anything he desired’. The same held true in prisons for criminals: in Newgate, when the Artful Dodger is awaiting trial for pickpocketing, Fagin promises, ‘He shall be kept in the Stone Jug...like a gentleman...With his beer every day, and money in his pocket.’

Tradesmen routinely conducted business in the prisons too, as they did outside. When Pip visits Newgate – a holding prison for those awaiting trial, as well as for convicted prisoners awaiting transportation or death – he sees ‘a potman...going his round with beer’ as such sellers did on the streets (see pp. 287–8; p. 292, top row, centre, shows a picture of one). Debtors were not necessarily kept off the streets altogether anyway. Around most of the debtors’ prisons there was a designated area where, on payment of yet another fee to the prison officials, prisoners could work and even live within

what were known as ‘the rules’. They comprised, Dickens wrote in

Nicholas Nickleby

, ‘some dozen streets in which debtors who can raise money to pay large fees, from which their creditors do

NOT

derive any benefit, are permitted to reside by the wise provisions of the same enlightened laws which leave the debtor who can raise no money to starve in jail’. One memoir claimed that the rules were so little policed that one prisoner deputed for the stagecoachman on the London–Birmingham route for an entire month without the prison officers being any the wiser. Many prisoners still worked at their old trades: in the 1830s, the cabinet-maker William Lovett was employed by a man who ended up in the Fleet, continuing to work for him in a workshop in the rules. Those in the Queen’s Bench didn’t even need to go outside the prison walls to resume their trades. On the ground floor of the gaol a number of indebted tradesmen turned their rooms into shops: butchers, greengrocers, a barber, tailors and so on. This group rather looked down on the row of rooms at the back of the building, where the poorer prisoners lived, and where ‘there are shops of an humbler class’: sausage seller, knife- and boot-cleaner and a pie seller.

When Dickens placed the Dorrit family in the Marshalsea prison off the Borough High Street, south of the river, he made it world famous, although at the time readers were unaware of his own intimate childhood experiences within its walls. By the time he began

Little Dorrit

in 1855, most of the debtors’ prisons had been closed down – the Marshalsea was emptied in 1842 – and there were only 413 debtors imprisoned in London. It is not surprising, given the author’s youthful scarring, that the novel was set during the years that the Dickens family too had suffered. William Dorrit enters the Marshalsea in about 1805, but most of the scenes there take place when he has already been imprisoned for two decades, almost exactly coinciding with the date when John Dickens was there – 1824.

The prison, wrote his son, was ‘an oblong pile of barrack building, partitioned into squalid houses standing back to back...environed by a narrow paved yard, hemmed in by high walls duly spiked at [the] top’. But the novel barely scratched the surface of the reality that was the Marshalsea. Just over a decade after his father’s imprisonment, Dickens, in

The Pickwick Papers

, had been more passionate about the conditions in the Fleet: ‘poverty

and debauchery lie festering in the crowded alleys; want and misfortune are pent up in the narrow prison; an air of gloom and dreariness seems...to impart...a squalid and sickly hue.’ Even this was an understatement. The prisoners’ lodgings in the Marshalsea consisted of fifty-six rooms measuring ten feet, ten inches square, each of which comfortably held one bed, although each routinely housed three prisoners. The narrow paved yard that Dickens mentions was really an alley, five yards wide at the widest point. There was, for the 150-odd prisoners and any additional family members who moved in for lack of funds to live elsewhere – as Mrs Dickens and their younger children had been forced to do – a single water pump, a single cistern to hold the drinking and washing water, and two privies. The yard was flooded with waste water, the open drains were ‘choked and offensive’, the dusthole, where rubbish and fire ashes were thrown, smelt, although not as badly as the privies: they were emptied only once every two months, and their stench carried to the kitchen.