The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage (17 page)

Read The Venetian Empire: A Sea Voyage Online

Authors: Jan Morris

Tags: #Mediterranean Region, #Venice (Italy), #History, #General, #Europe, #Italy, #Medieval, #Science, #Social Science, #Human Geography, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues

So Kyrenia, with its restrictions and its half-reminders, must have been a homesick place. If you sit up on the walls there alone on a summer evening, when the stars hang resplendently over the mountain behind you, and the little town has gone to sleep, then the slap, slap of the water on the rocks below may remind you naggingly of the water-noises of the Serenissima, and the feel of the old stone, slightly rotted, is like the feel of a garden wall beside the lagoon on Giudecca, and for a moment you may feel yourself at one with those poor Venetians who, loathing the island exile, watching the dark sea anxiously for the splash of the corsairs’ oars, wished themselves safely home and happy beneath the bright lights of San Marco.

The news of the fall of Nicosia reached Venice in seventeen days and the Signory was plunged in despair. Still, all was not lost. The combined fleet of the Holy League was at that moment assembling for a trial of strength against the Turks. The Arsenal, far from being crippled by the fire, had turned out one hundred new ships in the past year. And the defences of Famagusta, the Turks’ next objective in Cyprus, were said to be the strongest in the world -the apogee of Renaissance military architecture.

All its walls still stand, with their two gates. The Sea Gate has a great winged lion upon it, and a couple of demi-lions recumbent inside, one so crumbled as to be anatomically unrecognizable, the other badly gnawed away by time around the haunches. The Land Gate stands astride the road to Nicosia, with a powerful ravelin above. Between the two is the main bastion of the defences, the Martinengo Bastion, almost a mile square, and at the water’s edge is the Citadel, only a shell now, romantically called Othello’s Tower, but in Venetian times a formidable structure with four towers and its own moat. The two gates, the bastion and the citadel are joined by a tremendous wall, generally fifty feet high and often more than twenty-five feet thick: a ditch surrounds the town on three sides, and on the fourth side is the sea.

Within these works there is an air, nowadays, of shattered resignation. Famagusta has seen terrible things even in our own

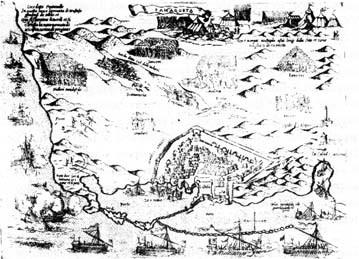

Famagusta under siege

Famagusta under siege

time – it was bitterly fought for in 1974, when the Turks kept it from the Greeks. In the north-west corner of the town, immediately beneath the walls, a sort of urban wilderness extends, like a bomb site or an unfrequented car park, and amid its emptiness stand the hulks of three churches, all in a row – ruins every one, very old, very sad, and pungently suggestive of lost consequence. The cathedral square in the middle of the town, now a hangdog provincial kind of place, where policemen pick their teeth on street-corners in the heat and shopkeepers loll the hours away sitting backwards on their pavement chairs – the cathedral square is a forlorn shadow of the days when it was the centre of Venetian power in Cyprus.

Although the town may be broken and shabby, it is well-proportioned still and somehow commanding, like some stout old dowager gone down in the world. The cathedral of St Nicolas is still there, with its great rose window, though it was long ago turned into a mosque; its facade is lopsided now because the Turks put a minaret upon its north tower, and most of its windows have been filled in with arabesque patterns of plaster of Paris, but it is still recognizably descended from Rheims or Amiens.

Directly opposite, across the dusty square, rises the grand facade, all that is left, of the Venetian Lieutenant’s palace. It has been badly knocked about in one war and another, and is now all mixed up with the adjacent police station, whose trucks are parked in its shattered courtyard, and whose trembling detainees are sometimes to be seen briskly escorted towards the cells. A pile of Turkish cannon-balls gives it a martial flavour still, and above its precarious central arch you can make out the arms of the Venetian nobleman, Giovanni Renier, who governed Cyprus during its construction.

There is a ruined Franciscan church just in sight beyond the square, bits and pieces of Venetian stonework lie here and there, and when a gust of wind blows up, dust from old Venetian masonries still swirls upon the air. Down the road to the south Othello’s Tower, only a few hundred yards away, marks the presence of the sea. Beside the cathedral stand two grand old pillars, doubtless filched from Salamis too, which were the symbols of Venetian sovereignty.

We are looking at the scene of the grand tragedy which, in 1571, marked the end of Venetian rule in Cyprus, and gave a famous martyr to the Republic. Here was Grand Guignol. Famagusta bravely resisted the Turks for ten months, long after the rest of Cyprus was lost. It was an allegorical kind of siege. The Turks were commanded by a general known to history only as Mustapha Pasha, a sort of generic Islamic commander. The Venetians were led by Marco Antonio Bragadino, Captain of Cyprus and a member, as they preferred, of one of their oldest noble families. Even the style of fighting fitted. Sometimes there were single combats between champions, watched by crowds of soldiers and citizens, and often messages of threat or defiance were exchanged between the combatants, as jousting knights might exchange courtly abuse between charges.

The Venetians fought with great spirit. Once they pretended to have abandoned the city, and when the Turks moved in for the capture, mowed them down with gunfire and slashed them about with cavalry charges. Once they recaptured one of their own standards, taken by the Turks at Nicosia. They made daring sorties, they scattered poisoned nails outside the walls, to disable

the enemy cavalry. The Turks, for their part, invested the city with their usual massive determination, appallingly wasteful of lives and money, but true to their own code of moral and national duty. They had at least 200,000 men to invest some 8,000 defenders, and fresh troops kept pouring in from Syria to keep their army up to strength. The Pasha was advised by a Spanish military engineer, until he was killed by a mine, and his corps of 40,000 Armenian sappers dug an enormous mesh of deep trenches all around the town – so big that the whole army, it was said, could be concealed within them, and so deep that tents were pitched inside, and cavalry could move about unseen. At the head of these subterranean approaches they filled in the town ditch and built two forts, of oak and earth, which towered castle-like above Famagusta, so that they could bombard it constantly and at almost point-blank range.

Bragadino was undeterred. One day, he told Mustapha after another of the Pasha’s repeated calls for surrender, the Venetian fleet would arrive to relieve the city and destroy the Turkish army: ‘Then I shall make you walk before my horse and clear away on your back the earth you have filled our ditch with.’ He lived to regret this choice of threat. A Venetian squadron did fight its way in after a brilliant little action, but it sailed away again to Crete, taking with it all the Venetian children of the city. After that, no more help came. By July 1571 life was so terrible within the town that the citizens petitioned the general to surrender. Bragadino replied by asking the Bishop of Limassol to say a public mass in the cathedral, with Bragadino himself as his server, and then appealing to the congregation to hold on for fifteen days more. Nearly all the food had gone by now. All the cats and donkeys had been eaten, and only three horses were left alive. The ammunition was almost spent.

For fifteen more days, nevertheless, they stuck it out as their general asked, ceaselessly bombed and repeatedly mined, quenching fires, repairing shattered revetments, fighting hand to hand battles now at one corner of the walls, now another, until the garrison was reduced to half-starved men, the Bishop of Limassol was dead like Paphos before him, and even the indomitable Bragadino was exhausted. Only seven barrels of powder were left

in the magazines: on 1 August 1571 they raised the white flag on the ramparts.

The Turks are said to have lost 50,000 men in the siege of Famagusta, and in return they had practically razed the little town, leaving to this day that air of abandoned defeat we felt inside the walls. When at last Bragadino surrendered, Mustapha promised him that the garrison might sail for Crete with full honours of war. For what happened in the event, history has generally relied upon the word of the Venetian chroniclers: Turks say that Bragadino broke the surrender terms by putting some of his prisoners to death, but it is the Venetians’ account that has prevailed, and here is their version of the end at Famagusta in 1571.

Mustapha Pasha ordered a fleet of twelve ships to embark the surrendered garrison, and on 3 August the embarkation began. Two days later Bragadino set off for the Pasha’s camp to take him the keys of the city, before boarding the galleys himself. He wore his purple robe of office, and above his head was held the red umbrella which was the prerogative of his office. He was escorted by some three hundred of his officers and men. They were conducted to the Pasha’s camp, where they were courteously required to give up their arms, and Bragadino and his senior officers were taken into Mustapha’s pavilion. At first the Pasha was polite, but after a few moments of conversation he flew into a rage. He accused Bragadino of breaking the surrender terms, and of squandering thousands of Turkish lives by a needless and hopeless resistance.

Suddenly the Venetians were seized and bound, and the soldiers outside the pavilion were fallen upon by the janissaries and cut into pieces. Only a handful escaped, not always by the most comfortable means – Hercules Martenigo, scion of a famous aristocratic clan, became a eunuch’s slave. Bragadino was made to kneel for execution, three times, but each time the axe was stayed at the last moment: Mustapha himself then cut off the Venetian’s right ear, while a soldier removed his left ear and his nose.

Twelve days later, horribly mutilated and pitifully weak, he was dragged back into the city, and his old threat to the Pasha was

turned against him. He was made to carry heavy sacks of stone and earth up and down the ramparts, kissing the ground each time he passed Mustapha. Then they tied him in a chair and hoisted him to the yard-arm of a galley, for the army and the citizens to see: and then, taunted all the way, hit by anyone who cared to, jeered at constantly by the Pasha himself, he was taken to the square beside the cathedral, opposite the palace, and tied face front to one of the Venetian pillars.

Mustapha Pasha sat in the loggia of the palace, and offered Bragadino his life if he would become a Muslim. Bragadino, one supposes, was past apostasy by then, and so in agony he faced the pillar, while an executioner flayed him alive in the sunshine. His head was stuck on a pike (where it shone like the sun, so Christian legend was to say, and gave forth a lovely fragrance). His body was quartered, and the various parts were distributed among the breaches the Turks had made in Famagusta’s walls. His skin, stuffed with straw, dressed in his purple robe and surmounted by his red umbrella, was carried around the streets of the city on a cow, before being slung to the yard of a warship and taken on a triumphal cruise around the eastern Mediterranean, now truly a sea of Turks.

Finally it was taken to Constantinople by Mustapha Pasha himself, and presented as a trophy of victory to the Sultan. It was placed in the Arsenal in the Golden Horn, directly opposite the place where, 350 years before, the Venetian forces had broached the walls of Constantinople and begun their imperial history. In 1650 a citizen of Verona, Jerome Polidoro, was persuaded by the Bragadino family to steal it. It was brought to Venice, and laid at last, all torments ended, in the church of San Zanipolo. As for Polidoro, the Turks caught him and tortured him appallingly, but he was ransomed by the Bragadinos, and given a pension of five ducats a month by the grateful Signory.

So there came to an end the brief and unhappy Venetian domination of Cyprus, 1489 to 1571. Two months after the fall of Famagusta the Holy League achieved a great victory over the Turks in the battle of Lepanto, but it was too late to save the island. Hardly a Venetian was left in Cyprus then: only a few

noble families, it is said, their lives spared by the Turks, melted into the peasantry and remained for another 300 years, from their village of Athenion in the central plain, the chief muleteers of the island. The Turks remained sole rulers of Cyprus until the nineteenth century, but they did not bring it contentment. Stagnant and divided the island festered on, until the memory of the Venetians was almost lost and nothing was left of them there but the ruined and fateful walls of fortresses, a church or two, a winged lion here and there. They had earned no gratitude, and gained little love, from their anxious generations in the bittersweet island.

But what, you may ask, became in the end of Caterina Cornaro, whose sad marriage all those years before had brought Cyprus into the Signory’s grasp? She was lucky to have abdicated, as it turned out, for the second half of her life proved much happier than the first. She never married again, and a portrait of her in middle age, by Gentile Bellini, shows her massively shouldered and busted, with her hair cut short, her mouth resolute and her rather porcine eyes displaying a slight but distinctive outward squint. Instead she devoted herself to cultural and social pleasures, and became in later years a famous patron of the arts.