The Various (36 page)

Authors: Steve Augarde

Henty looked across the yard, beginning to feel the panic rising inside her. Where could she hide? The line of byres, she knew, had provided a haven for the woodlanders but they also housed the felix – when it wasn’t lurking elsewhere. At the end of the yard stood a larger byre, and she could see that one of the great doors was slightly ajar. Ducking low, beneath the level of the steps, she braved the gap at the end of the path and then sprinted down the full length of the yard, her bare feet soundless on the mossy cobblestones.

She reached the great rust-coloured doors of the cider barn, and glanced, terrified, over her shoulder in case she was pursued, then, finding that she had apparently been unobserved, looked cautiously around the open door. Great metal stanchions loomed in the darkness at the far end of the barn, with

a

massive cross beam and various crates and wooden constructions, broken barrels, planks, stone jars as tall as she, and all the paraphernalia of an industry long abandoned. Stepping into the gloom, her nose wrinkled at the unfamiliar smell of cats and the ghosts of countless fermentations. A high ladder, she could see, fixed to a great upper platform that spanned the width of the barn and projected forward to perhaps a third of its length. This was the old apple store and to Henty it seemed as though it might provide a safe haven, although she doubted that she could scale the ladder – the rungs would be almost waist high to her. However, she wasn’t here to hide, but to find what she had come for and then return with all speed to the forest. She ran back to the door once more and looked down the yard. What she saw then made her gasp with fright.

Emerging from beneath the broken door of one of the near byres, was the felix.

The

felix. Then she understood. Then she knew the terror of that recent night, when Lumst had lost his life. It was the biggest animal she had ever seen.

Tojo stretched and yawned, extending his sabre claws to the full and displaying the fearsome capacity of his gaping jaws. He looked towards the barn. The door was open. With his great brush of a tail almost touching the ground, and his flat broad head held low, he began to make his way purposefully across the yard.

Henty found that she was able to scale that ladder after all, and quickly. Throwing herself down on to the

boards

of the apple loft, she peered in terror over the edge, just in time to see the shadow of Tojo appearing in the doorway below. The monster slowly entered the barn, sniffing the ground, his baleful yellow eyes scanning the gloom. His wives and children were apparently absent. No matter. They would return. He sat in the doorway, a grim sentinel, occasionally squeezing his eyelids shut, tail ceaselessly twitching.

Henty could feel her heart pounding against the dusty boards, her breathing painful and shaky. She was trapped.

Chapter Twenty-one

GEORGE WOKE BEFORE

Midge, rolled over a couple of times, and finally sat up, resting his head and shoulders against the back wall of the tree house. He looked at his watch. Not even six o’clock, but already he could feel the heat of the sun, warm on his shoulders, through the rough wooden panelling.

It was like sitting in a cinema. In the dim interior of the three-sided wooden house, the open end became a bright oblong screen, with all the early morning world showing in brilliant technicolour – a slow moving nature film, in real time. A bird or an insect would appear in the frame, play out its part, and then disappear off-screen once more. From his low position on the army camp bed, it was the upper branches of the cedar that were visible – foreign, they looked somehow, exotic, in searingly bright colours against the pale morning sky, the sun shining on the dewy branches and defining every powder-blue needle, every glistening cone.

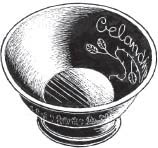

Midge was still asleep on the other side of the ammo box. He looked at the little metal bowl she had placed on the box the night before. When he had asked her

what

it was, she said that she would tell him some other time, he could have a look at it some other time – like it was some sort of mystery. She was tired, she said, and anyway it was too dark by the light of the tilly lamp to see it properly. Well, now was some other time, so, in that case, she wouldn’t mind if he had a look. He reached across and gently picked up the bowl, feeling the strange weight of it. It was engraved in some way, and he held it up to the light, frowning slightly as he tried to make out what it could be. He licked his fingers and rubbed them on the grubby metal surface. A crowd of tiny figures he could see – encircling the outside rim, like something from an old painting, mediaeval perhaps – in what seemed to be belted smocks, hoods, and tight leggings, or maybe just bare legs, and bare feet. All wore the same open-mouthed expression. George smiled. It looked as though the whole lot of them had just seen a ghost. He turned the bowl some more, made it wet again, and found a much larger figure, twice the height of the little ones. It was a girl – and she was different, not just bigger, but different in some other way. Strangely dressed, yet still more . . . modern. She too had her mouth open. Weird.

A disturbing and unhappy thought suddenly came to him. This was like Midge. This was like her story, about seeing little people.

This

was where the idea had come from. She had found this thing, picked it up from somewhere, and had invented a story about herself. It must have taken her ages to think it all up. That was even more weird.

George looked inside the bowl. There was something else engraved around the inner rim – but his tongue tasted funny now, and he couldn’t be bothered with it any more. He felt sad, and worried – it just wasn’t . . .

normal

to make all that stuff up, was it? That was, like . . . what did people say . . .

disturbed

, wasn’t it? He quietly reached over to replace the bowl, pausing for a moment to look wonderingly at the sleeping form of his cousin as he leaned across the ammo box. She was huddled up in her quilt, her back to him, just the top of her head visible. Poor Midge. He’d never really thought about what it must be like to be someone else – what it must be like to be . . .

There was a dry flapping sound, brief and startling, and a sudden rustle of foliage as something alighted in the cedar tree outside. George looked up, and felt his neck lock solid. His mouth fell open as if he might scream, yet his breath so failed him that he couldn’t even gasp. Some fantastic creature – like a winged monkey, an impossible thing – was clinging to the slim upper branches of the tree. The spiky blue cedar fronds swayed up and down in the framed oblong of brilliant colour, as the creature

gained

its balance and folded its wings. It had its back to the open end of the tree house – but there was no doubting what it was, and it was just as Midge had described. George was quite unable to breathe, or even to move, and remained frozen in the act of replacing the metal cup. He heard the thing sniff, and his amazement turning to creeping horror as the figure slowly turned, still swaying slightly on the cedar branch, to peer directly into the tree house.

Its jaw was long and its mouth hung open slightly. The eyes, screwed up tight against the dazzling sunlight, were set low and deep, beneath a heavily jutting brow and a bedraggled crop of wispy hair. It lifted a skinny brown hand as a shade against the bright glare, ducked slightly, and stared straight at him. The dark eyes were open now, glints of light visible beneath the shadow of the small weather-beaten hand. George shrank back against the end wall, certain that his presence would now be obvious – yet the expression on the thing’s face remained dull, inanimate, the jaw still hanging slightly open. It turned away, and gazed in the direction of the farmhouse. George was astounded that the creature had apparently not seen him – but still he dared not, could not, move. The glare from the sun, shining above the roof of the tree house, must have made the dark interior invisible.

Yet, from his perspective, every tiny detail was lit with amazing clarity. He could see the rough stitching on the greasy leather quiver that was slung over the miniature monster’s back – the bat-like wings, folding and unfolding, flexing like a man might flex his

shoulder

blades, and the curious designs, coloured tattoos, that covered the semi transparent membranes. He saw the tiny orange hairs among the grey squirrel-tail cuffs that adorned the wrists and ankles, the small but sturdy looking longbow, hung with a tuft of magpie feathers at one end, the incongruous knee-length britches made of black corduroy, worn threadbare across the seat – which were held up, even more surprisingly, by a grubby elastic belt, black-and-white striped.

At last George let out his breath, in as quiet and controlled a way as possible, and gently,

gently

replaced the bowl on the ammo box. This was

something

. This was . . .

the

most amazing something . . . He looked across at Midge and wondered how to wake her. Her fair hair was still visible above her duvet cover, and she slept on, peacefully. George saw in an instant all that she must have been through, and his heart went out to her. He hadn’t believed her. Thought she was crazy. Well, he believed her now – and would make up for his doubting her, if ever he could. Because this was

something

. . .

The creature in the tree had stiffened, was now suddenly alert. It was staring intently into the distance – had obviously spotted some approaching danger. The body sank into a crouch, and the skinny brown fingers rested lightly on the branch, a pause, a slight raising of the head, quickly ducking down again, and then the wings opened out to full stretch.

Dregg was not the brightest of the West Wood archers, but he recognized danger – when he could

see

it. He launched himself silently from the branches and was gone.

George gaped in open-mouthed wonder at the now empty vista at the end of the tree house. The cedar tree ceased to sway, and stood, snapshot still, against the cloudless sky. He heard the slight crack and tick of the timber wall panel behind him as it expanded in the heat.

‘Midge!’ he whispered, urgently, elatedly, ‘Midge! Wake up! I’ve seen one!’

Midge turned her head slightly. ‘Wha? Hnn?’

‘Wake up, Midge! I’m so – I can’t

believe

this . . .’

‘George?’ It was his father’s voice, slightly muffled, coming up from ground level. ‘Midge? Are you awake?’

‘Dad?’

What was going on? Why was his dad here? There was a heavy creak and a slight movement of the tree house as his father began to ascend the rope ladder. Midge sat up as Uncle Brian clambered up the ladder and appeared over the edge of the wooden platform. ‘Phew!’ he said, staggering slightly as he stood up, ‘Getting too old for this malarkey. Are you awake, you two? Probably weren’t – I

am

sorry. Really – I’m sorry – but I’ve left it as late as I dare. Midge – well, both of you, I’ve had some bad news. Well, sort of bad news – nothing too alarming, but, um, not too good either.’ He sat on the end of the ammo box, facing Midge – who was still barely awake. ‘I’m sorry, sweetheart, you’re still half asleep. Listen, Midge, it’s your mum, I’m afraid. Don’t – no, it’s OK, don’t worry, she hasn’t come to any harm.

Look

, let’s go into the house – have a cup of tea or something – and I’ll tell you all about it.’

‘No!’ said Midge, her eyes now open, and wild with alarm. ‘What’s happened to Mum? What’s going on? Tell me now!’

‘Well, all right. But I don’t want you to

worry

. She’s had to pull out of her tour.’

‘What? Why?’

‘She’s not . . . feeling too good. She’s not . . .’

‘What do you mean? Is she ill?’ Horrible thoughts were racing through Midge’s head. Horrible things . . .

‘No, not exactly. She’s not feeling up to it. She just can’t . . . do it any more. It’s like her nerve has gone. It’s all just become too much for her. She phoned late last night, long, long after you’d gone to bed. I didn’t want to wake you then. She’s

OK

, Midge, really, she’s OK – you mustn’t go imagining the worst, but for the moment anyway, she’s out of the tour. She wants to – well, I persuaded her – to come down here, take it easy for a few days. It’s just pressure, I think. It can happen in any job. Anyway, she didn’t want to travel by herself, so I said I’d go and pick her up. And that’s why I’ve come to wake you. I’m going up to London to meet her, and then I’ll come back down with her.’