The Valentino Affair (49 page)

Read The Valentino Affair Online

Authors: Colin Evans

Blanca didn’t have long to wait for the courts to clarify her custody concerns. On March 11, after two months of deliberation, Surrogate Fowler rejected claims that as an American citizen, Jack Jr.’s interests would be best served by his being raised by the de Saulles family and instead awarded permanent custody to Blanca. The nomadic mother and son were notably absent when the verdict was announced, and not until three days later did reporters track them down, this time in Japan, at a villa a few miles outside of Tokyo that Blanca had rented for the summer. She intended to stay there, she said, until the notoriety surrounding her name died down.

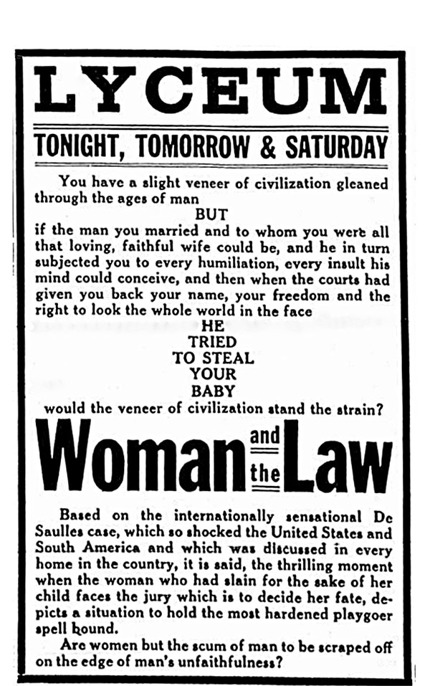

Not that there was much chance of that. Within weeks of the custody issue being decided, a “quickie” movie called

The

Woman and the Law

opened at the Lyric Theatre in New York before hitting screens nationwide. Written and directed by Rauol Walsh, and based on the de Saulles case, it starred Walsh’s wife, Miriam Cooper, as Blanquetta La Salle. Because of Cooper’s strong resemblance to Blanca, it was rumored that the distributors, Fox, originally wanted to leave Cooper’s name off the credits to create the impression that Blanca had played the part herself. According to the press releases, the film posed such moral conundrums as: “Are there provocations which justify a woman to kill?”

35

and, “Has the law the right to deprive a mother of her child?”

36

These questions, it said, were decided by the jury “in a scene that will live long in the memory of every one who sees it.”

37

Because of its controversial subject, the meaty drama was rated as suitable only for audiences older than age twenty-one. One reviewer proclaimed it “the greatest woman’s picture ever staged.”

38

Sadly, this film has been lost to history.

After this flurry of publicity, interest in Blanca waned, leaving her free to resume her globe-trotting lifestyle in peace, with Jack Jr. at her side.

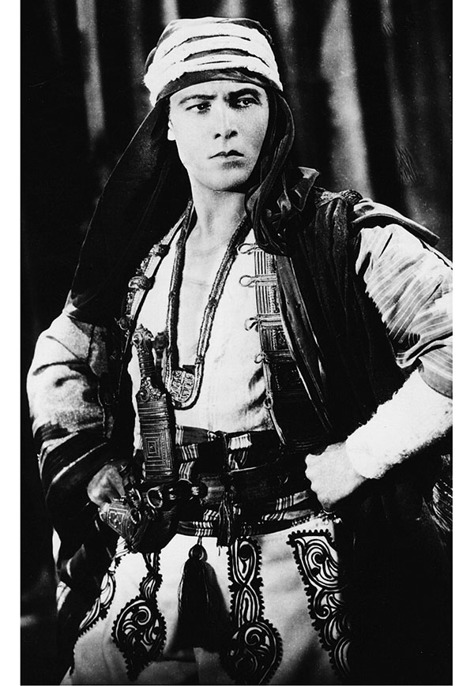

Miriam Cooper in

The Woman and the Law

(1918), based on the de Saulles murder case

Contemporary newspaper advertisement for

The Woman and the Law

The Jack de Saulles estate was proving even more troublesome than originally thought, as attorneys wrestled to unravel the financial mess left by Jack’s intestacy. An initial valuation assessed his total estate at $68,380, made up of $53,380 in bonds, securities, and cash, and realty worth $15,000. Under the law Blanca was entitled to her dower interest in the realty, while the remainder of the estate went to Jack Jr. in trust until he reached majority. The estate was administered by Charles de Saulles in conjunction with the Nassau County Trust Company, and getting to the bottom of how much Jack really owned and, more important, how much he owed, was a financial headache that would drag on for another eighteen months.

To ease the burden, the administrators decided to offload The Box. When it came on the market, its star-crossed history repelled most buyers, and it was eventually sold on August 5, 1918, to Thomas H. Bowles of Kansas—the only bidder—for the knockdown price of $19,348. Documents and receipts showed that Jack had spent close to fifty thousand dollars on renovations. This didn’t surprise anyone. What did raise eyebrows in the financial community was the revelation that Jack didn’t even own the house. It had been purchased in September 1916 by his longtime business associate, Stephen S. Tuthill, for twenty-eight thousand dollars, using an eighteen-thousand-dollar mortgage held by prominent local landowner Mrs. Emily Ladenburg. Tuthill had then leased The Box to Jack. When held up to the light, the deal turned out to be considerably less sinister than first appeared. With his marriage on the rocks and a divorce pending, Jack wanted as few assets in his own name as possible, and the likelihood is that he transferred ownership of The Box to Tuthill’s name to keep it out of Blanca’s clutches should any settlement go against him. When the mortgage matured without anything having been repaid on the principal, Mrs. Ladenburg foreclosed.

As the months passed, and with the principals either dead or else scattered around the globe, memories of that awful night at The Box began to fade. But they were brought back into sharp relief on January 11, 1919, when fifty-one-year-old millionaire sugar baron and notorious eccentric Jacques Lebaudy, known as the “Emperor of the Sahara,”

39

was shot and killed at The Lodge, in Westbury, just a stone’s throw from where Jack had been gunned down. A string of coincidences connected the two killings. First, there was the location; second, Lebaudy died from five gunshot wounds; third, the weapon used was a .32 revolver; fourth, the arresting officers were Sheriff Seaman and Constable Thorne; and fifth, the confessed shooter was the dead man’s wife.

“Yes, I shot him,” Augustine Lebaudy admitted. “He deserved it. But I will go free. Look at Mrs. Carman and Mrs. De Saulles.”

40

Once again responsibility for the prosecution fell to the long-suffering Charles Weeks, and this time the case didn’t even make it to trial. Ten days after the shooting, the grand jury refused to indict, saying that Mrs. Lebaudy had clearly acted in self-defense. Because there were no witnesses to the shooting, the verdict caused a degree of surprise, although many cynics attributed the grand jury’s leniency to its belief that anyone with Lebaudy’s bizarre habits—among other peculiarities, he liked to ride cows bareback, though he was unsuccessful in his attempts to make them hurdle—probably would benefit from a bullet in the back.

So, once again a wealthy female defendant had escaped the electric chair after killing her husband. Such homicides were now becoming a national epidemic. And, once again, Chicago had spearheaded this courtroom bias. When, in April 1918, Ruby Dean became the twenty-fifth women in barely ten years to be acquitted of murder in Cook County, prosecutor Justin McCarthy wearily observed that the shooting of a man by a woman had become “the king of indoor sports.”

41

Christmas 1918 saw the final winding-up of Jack de Saulles’s estate, and a very messy affair it turned out to be. When the numbers were finally calculated, they showed that Jack had died heavily in debt. Renovating The Box had ruined him financially. At the time of his death, he owed $53,881 and had assets of just $29,932. Creditors got less than fifty cents on the dollar. Jack Jr. got nothing.

Not that he needed it. The youngster was now being raised in the grand style on his mother’s estate in Viña del Mar, enjoying all the trappings of wealth that the vast Errázuriz-Vergara family fortune could bestow. After her return from Japan, Blanca had declared that she would never remarry, but it was hard to imagine this fun-loving society butterfly signing up to a life in widow’s weeds. Just like a decade earlier, there was no shortage of suitors beating a path to her front door, and this time the victor in the contest for Blanca’s hand was a wealthy Chilean engineer named Fernando Santa Cruz Wilson. The couple married in Santiago on December 22, 1921, just three days shy of Jack Jr.’s ninth birthday. According to one paper, Blanca chose Fernando because her “little son is such an ardent admirer of Sénor Wilson and has long been anxious to have him for a stepfather.”

42

It was reported that Wilson and the boy were inseparable companions, and he took the youngster hunting.

But calamity never strayed far from the blighted Errázuriz-Vergara family. Just a few months later, on May 1, 1922, Blanca’s brother, Guillermo, blew his brains out in a Parisian hotel after being rejected by the American actress and world-class gold digger Peggy Hopkins Joyce. Added irony derived from the fact that Peggy had played the role of Josie Sabel (based on Joan Sawyer) in the movie

The Woman and the Law.