The Valentino Affair (24 page)

Read The Valentino Affair Online

Authors: Colin Evans

But all these things will transpire in due time. I do not wish to bandy recriminations, but I must protect my brother’s name. He was not free from fault, but he was always generous and kindly in his treatment of her. He was loved by hosts of friends, and his memory will always be dear to them. I hope that the rage which caused his death will cease to pursue him in his grave, and that it will not be necessary for me as his brother again to defend his memory.

4

When details of this diatribe reached Uterhart, he wasted no time in drafting a response:

With respect to the extraordinary statement of Mr. De Saulles, I will only say so far as it concerns myself, that one of the most ancient devices known to the law is contained in the rule, “When you have no case, abuse the opposing counsel.” Mr. De Saulles glosses over as a matter of no importance the undisputed fact that it has been judicially determined that John De Saulles was an unfaithful husband and that his wife was granted an absolute divorce in this State upon the ground of his infidelity. If this constitutes Mr. De Saulles’s conception of “devoted and loving husband” he is welcome to his opinion.

The most important of the charges of Mrs. De Saulles against her husband were, in part, that he married her for her money, grew cold toward her when her fortune did not come up to his expectations, got $47,000 of her fortune of $100,000 by deceptions, became unfaithful early in their married life, took women companions into their apartment, and took the boy out with them, treated her brutally and contemptuously in the presence of her son and servants, and tried to destroy the boy’s affection for her.

5

As reporters struggled to digest this torrent of words, one of them threw Uterhart a curveball. If Blanca had such a skimpy income, how could she afford to rent a swell place like the Crossways for the season? Uterhart repeated the same story he had offered a day earlier: that in her fight to retain the affection of her boy, she was forced into “reckless expenditure . . . to offer him attractions equal to those which De Saulles, backed by the Heckscher millions, could offer.”

6

Uterhart, visibly nettled, steered the exchange back to Blanca’s worsening mental state, saying she had spent the day in bed, eating almost nothing and constantly asking to see her son—but the questions kept coming. Why did Mrs. de Saulles carry a gun with her on the fateful night? Uterhart’s response—“Because many women had been held up or alarmed by highwaymen in the lonely roads of Nassau county”

7

—fooled no one, least of all District Attorney Weeks. The outlandish assertion of “highwaymen” roaming the byways of Long Island brought forth a snort of contempt. The prisoner, Weeks said, “went there to shoot her husband. The killing of John De Saulles was a deliberate murder.”

8

He added that his department had uncovered all the evidence it needed to proceed, and he was confident of the outcome: “The State can put its case in less than forty-eight hours.”

9

Blanca had no complaints about her jailhouse treatment. “I have done everything possible for the comfort of Mrs. De Saulles,” said Mrs. Seaman, who was acting as personal chef and factotum to her celebrity inmate.

Her physicians have told me that she is very frail and that care should be taken to prevent serious illness; so I feel it my duty to personally supervise the treatment accorded her. Besides, it is a real pleasure to be able to do anything for the poor child, she is so deeply grateful for the smallest attention. I have never known a more refined and sweet-tempered young woman.

10

Mrs. Seaman further reported that when she asked Blanca if she wanted a priest, the latter had replied, “During my residence in the United States I have had no active connection with the Church, and I do not wish to have it appear that I think of such matters only in time of trouble.”

11

But everybody wanted a share of the de Saulles limelight. In San Francisco, actress Ruth Shepley resurfaced to claim that she had been secretly “affianced” to Jack, and she sprang to his defense. “When they call Jack De Saulles the most popular man on Broadway it makes me want to cry ‘unfair,’ ” she told a reporter as she curled up in an armchair in her suite at the Palace Hotel on Market Street. “Jack had the personality to be the most popular man in New York, not in the sense that ‘Broadway’ popularity is usually taken to mean.”

12

She insisted that she and Jack had intended to marry. “I loved him as much as a woman can love a man,” she said, adding elliptically, “and a woman can love a man like him more than any tongue can tell.”

13

On this same day, Marshall Ward also entered the verbal fray. At a hastily convened press briefing, the dead man’s business partner declared that Jack “was no Lothario. He was as clean and straight and honest a fellow as ever lived. Of course, to defend her they must throw mud at him.”

14

Then Ward twisted the knife. Blanca had attended the Carman trial, and it was that travesty of justice that gave her the idea that “a woman might commit a murder and come to be regarded as a heroine.”

15

Nor was it any coincidence that Blanca had appointed the same law firm that had defended Mrs. Carman. Ward toned down the rhetoric to tell how one day after the shooting Jack Jr. came to him and asked, “What did you do with my dad?” Ward said he had been unable to find the words to tell little Jack what had happened, but the lad had pressed, “You are going to tell me.” Ward said that his father had gone to the hospital. “Not for good?” asked the boy.

“No, he’ll be back soon, Jack,” Ward gently lied. “He’ll be all right.”

Their exchange seemed to comfort the little boy, who “adored his father.”

16

That night and the following morning, the dead man’s relatives and their lawyers thrashed out the details concerning visitation rights for Jack Jr. When asked earlier, Charles de Saulles had said, “No decision has been reached to refuse or consent, so far as I know. I will try to do . . . what is best for the boy’s welfare, and just what I believe my brother would have done and what he would want me to do.”

17

At meeting’s end, an announcement conveyed that Jack would visit his mother for the first time since the shooting. District Attorney Weeks, when advised of the decision, had no objection.

But first there was the business of the inquest into Jack’s death. It convened at the Old Mineola Courthouse, with Justice of the Peace Walter R. Jones acting as coroner. A frisson of excitement hung in the air, even before testimony began, from the revelation that overnight someone—smart money was on some press employee—had broken into Crossways and stolen a set of photos of Jack Jr. Testimony began at 2:00 p.m. with Dr. Harry G. Warner, who performed the autopsy. De Saulles had died from hemorrhages caused by several bullet wounds, he said, and he had extracted two of the bullets in his examination. Weeks brought out that the murder weapon was a five-chambered revolver, confirming that Blanca, in her rage, had emptied the revolver into her ex-husband.

Marshall Ward gave a graphic account of the shooting that didn’t differ materially from anything previously reported. After him, Sheriff Seaman and Constable Thorne described the circumstances of Blanca’s arrest. With these formalities observed, Jones called Suzanne Monteau. There was no response. Jones tried a second time, still no response. The maid was nowhere to be seen. Bemused court officers shrugged, and Jones, fighting back frustration, adjourned the inquest until a later date. When news of this development reached Uterhart—who hadn’t bothered attending the inquest—he protested that Miss Monteau’s absence followed a simple misunderstanding. She was, he said, in the jailhouse with her mistress—“not more than 75 feet from the room in which the hearing was held”

18

—and would have been perfectly willing to testify had she been made aware of the court’s wishes in advance.

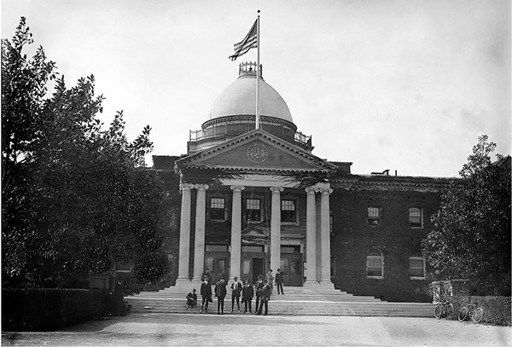

The Mineola Courthouse staged the “most sensational” trial in Long Island history, but a fire in 1981 destroyed the records and transcripts.

Having satisfied the court on this score, Uterhart went back to working the phone. All day long he had been conducting intense negotiations, and at 5:10 p.m. his efforts finally bore fruit when a large black touring car left the Heckscher home in Westbury. Twenty minutes later it pulled up outside the long, low, ivy-covered jailhouse in Mineola. Out stepped Ernest B. Tracy, a friend of the de Saulles family, with a private detective hired to safeguard the car’s third passenger. The two men lifted Jack Jr. from the backseat and walked him up the steps.

Flashbulbs popped to record the moment. The press had its first view of the innocent cause of this tragedy: a chubby lad, large for his age, smartly turned out in a white sailor suit, his mop of brown hair tucked into a straw boater. Jack Jr.’s arrival had been expected, so a uniformed turnkey swung back the main door without being asked. Inside, the boy cried, “Where’s mamma’s room? I want to see my mamma.”

19

Directed toward a flight of iron stairs, he scampered up, shouting, “Mamma! Mamma!”

20

Blanca stood in the doorway of her room. The boy ran up and threw himself into her waiting arms, almost knocking her over and sending his straw hat flying. Blanca smothered him with kisses; her frigid exterior melting instantly. For the first time since her incarceration, she wept.

Watching the scene, Estella Seaman also wiped away tears as the little boy asked, “How long are you going to be here, mother?”

21

Blanca was evasive. “A long time, I fear . . . but you mustn’t mind. Mother will come back to you.”

22

Throughout the half-hour visit, Blanca balanced Jack on her knee, not once letting him out of her sight. Every second of the reunion took place under the watchful eye of two witnesses—and a handful of carefully selected reporters. The only awkward moment came when the little boy asked, “Where’s daddy?”

23

and Blanca couldn’t find the words to answer. But Jack Jr. didn’t stop beaming the whole time he was with his mother, turning moody only when told it was time to leave. Blanca clutched him to her bosom for as long as possible and only surrendered him with the greatest reluctance, begging the boy to come again soon.

Earlier that day, before news that her son was on his way had revived her, Blanca reportedly had relapsed so severely that the sheriff once again called Dr. Cleghorn. The doctor found her in a state bordering on “collapse”

24

and “still losing weight at an alarming rate,”

25

something of a surprise considering the platefuls of food that Blanca was demolishing on a regular basis, according to Mrs. Seaman. He wanted to X-ray her, he said, to diagnose the mysterious malady from which she was suffering. Without much improvement in her health, he doubted that Blanca would be fit enough to stand trial. But Jack Jr.’s visit had wrought a miraculous change. Mrs. Seaman could scarcely believe the transformation. “She seems like a different woman. You would not know her.”

26

Two more developments rounded out the day. First came the surprise news that Jack had died without signing a will. For months his lawyers had urged him to remedy this oversight and had prepared several documents, only for him to postpone signing the instrument. His counselors first drew up the paperwork during the divorce proceedings, but Jack kept fiddling with the details, mostly as they applied to his son. The will indicated that he should attend public schools until he reached age thirteen, then a prep school, then Yale. While no details of the estate were released, estimates put his business income at more than fifty thouand dollars a year.