The Unknown Warrior (4 page)

Read The Unknown Warrior Online

Authors: Richard Osgood

A further question arises from this burial. Stonehenge was still an important monument in the Early Bronze Age, as demonstrated by satellite pictures showing the profusion of round barrows in the vicinity. Was this man, provided with rich burial goods, of high importance to the society that buried him â after all, he was within the bounds of the great ceremonial site, something that had not been achieved even by the âBush Barrow Chieftain', who had been buried close to Stonehenge, accompanied by lavish grave goods?

A stone archer's wristguard or âbracer', 110mm by 28mm, was found with the burial, with a circular perforation at either end to allow the item to be strapped to the arm or affixed to a leather backing. Three largely complete barbed and tanged flint arrowheads were also retrieved â the tip of one embedded in a rib, as we have seen. It is tempting to suggest that all three arrowheads were fired into the individual prior to death, with two of them causing soft tissue injuries hence they were lying loose on excavation. This seems especially pertinent given the presence of the other (fourth) arrow tip in the sternum. If we assume that all the arrows were embedded in the victim, he would only have been provided with a wristguard in burial. He would not have been given arrowheads, a copper dagger, gold items, or even the eponymous Beaker, and would thus have been quite poorly apparelled for someone buried in what was presumably a prestigious location. Was the fact that this man appears to have been killed in combat significant, and that his burial was one of a warrior hero in a sacred location to which his deposition might have added even more power, and was the wristguard worn by him in the fatal engagement? This is, of course, speculation, but it is a tempting scenario.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 1

The Beaker burial from Stonehenge in Wiltshire

This is the body of a young man shot several times from behind by flint arrowheads. There is no evidence to suggest that the man was executed; he was either murdered or died in combat. His presence in a burial at Stonehenge might suggest the latter â a further indication of a martial nature being his wristguard. The man was killed at the start of the Bronze Age when representation in death as a warrior was of great importance.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 2

In 1968 a gas pipeline was cut through fields in Tormarton, South Gloucestershire, uncovering a series of human bones. On closer examination these bones were thought to represent the remains of three individuals and were seen to have weapon injuries, including the presence of bronze spears transfixing some of the skeletal elements:

Skeleton No. 1 has in the pelvis a hole made by a lozenge-sectioned spearhead which must have been driven into the body by an attacker from the right side when the victim was either falling or had already fallen â¦

Skeleton No. 2, about a foot away, and in the same ditch or pit, exhibits features of even greater interest. Two of the lumbar vertebrae are stained blue-green by contact with a small Bronze Age spearhead, the blade of which was found, but the end containing the socket had broken off at the point of weakness behind the blade. This spear had pierced the spinal cord and would have caused immediate and permanent paralysis in the legs ⦠The skull has a hole perhaps caused by a blow or wound. (R.W. Knight

et al.

, 1972: 14)

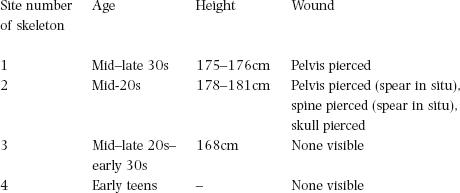

In 1999 and 2000, the author, along with the archaeologist Dr Tyler Bell (Osgood and Bell, forthcoming), returned to this site to establish the context for these burials and to examine whether more material was present. Initial site work soon revealed that the gas pipe had, in fact, truncated a segment of a V-shaped Bronze Age linear ditch, into which the bodies had been thrown. The ditch was around 2.2m wide at the top and around 1.4â1.5m deep, of a type found in many areas of southern England in the Middle and Late Bronze Age. A great deal of skeletal material was recovered and, when combined with the collection recovered in 1968, was examined by the palaeopathologist Dr Joy Langston. She concluded that there were now at least four, and probably five, individuals represented by this sample. All were male and their ages ranged from around 11 years to late 30s.

Table 1.1.

Details of the Tormarton skeletons

A radiocarbon date of 1315â1050

BC

was obtained from the humerus of the oldest male; the interface of the Middle and Late Bronze Age. An interesting point is that only two of the bodies displayed weapon trauma although they were presumably all thrown into the ditch at the same time. An analysis of the mollusca within the ditch indicated that the ditch had been initially cut through recently cleared woodland and was promptly backfilled.

The weapons used for this attack were clear, as parts of them are still embedded in their victims. A spearhead (the cross-section of which appears in the pelvis of Skeleton 1) was used to stab Skeleton 1 from behind. Another weapon was used on Skeleton 2; this man had again been speared from behind with such force that the spear passed straight through his pelvis, and snapped off when the assailant tried to remove the weapon, leaving it within the body. A spear thrust to the same man's back had the same result with the weapon piercing the spinal column, a wound that would have resulted in the instant paralysis of the individual, and then becoming stuck â breaking off when the spear shaft was pulled to remove the weapon. If this was not enough, when this young man then fell to the ground as a result of his wounds, he was dealt a sharp blow to the side of his skull that would have killed him. It is possible that this was administered with the shaft butt (or ferrule) of the broken spear as the wound is circular.

In both cases the wounds were inflicted from behind in a savage attack although others that may have left no trace on the skeleton might also have occurred â after all, the other individuals had no clear signs of weapon trauma. Why, though, were they attacked? It is my belief that the context is of great significance. The bodies were found in a linear ditch of a type that marked out territories and parcels of land in the Bronze Age, claiming areas for different groupings. The fact that these men were thrown into such a construction, which was then backfilled so soon after its cutting, may suggest that they were killed as part of a territorial dispute. One group had claimed the land and this claim had been disputed in the most violent of fashions.

One final note is that Dr Peter Northover's analysis of the metallurgy of the spear that ended up embedded in the back of Skeleton 2 pointed to the fact that the allotting of the tin and copper to form the bronze had originally taken place somewhere in the Alps. The spear itself was formed from this metal once the alloy had arrived in Britain. As such, it serves to indicate the long-distance trading of precious materials in this phase of prehistory (Northover, in Osgood and Bell, forthcoming).

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 2

The body of a man killed in a territorial dispute at Tormarton

This man had suffered a brutal attack, probably in a territorial dispute, in the Middle to Late Bronze Age. He had been speared in the back and pelvis with such ferocity that on each occasion the spear had broken off and remained in the bone. Once the man had fallen to the ground, he was finally killed by a blow to the head. The man was in his mid-20s when he died and was quite tall, being some 178â81cm in height. Analysis of his skeleton showed that the lowest lumbar vertebra had fused to the top of the sacrum although the man would have been unaware of this ailment. His skeleton also bore traces of Schmorl's nodes indicative of him having lived a fairly active life. No dental disease was noted on this man. Skeleton 2 from Tormarton is to date the most unequivocal evidence for combat in the Bronze Age of the British Isles.

TWO

Under the Eagle's Wings: In the Service of the Roman Legions

The Romans were faced with very grave difficulties. The size of the ships made it impossible to run them aground except in fairly deep water; and soldiers, unfamiliar with the ground, with their hands full, and weighed down by the heavy burden of their arms, had at the same time to jump down from the ships, get a footing in the waves, and fight the enemy â¦

(Caesar,

The Conquest of Gaul

, IV, 3: The First Invasion of Britain, 55

BC

)

One could write a huge volume on a particular type of Roman armour, on weaponry of the legionary, on graffiti found on pottery within a military context. I am simply trying to draw together some of the strands of evidence. Archaeology is only one source of information on the Roman soldier. I shall, however, stick to archaeology as far as possible when examining the life of the legionary â be it finds from military battle sites, or fragments of writings uncovered on excavation sites. Thus, while it is possible to draw information from written sources on elements such as the pay of the Roman soldier, I shall not be doing so. The Roman Empire spanned several centuries, but here I shall focus on the Roman soldier of the first couple of centuries

AD

, on the legionary soldier rather than the auxiliary â the latter without citizen status. Many of the examples are drawn from Britannia, the most far-flung post of the Empire.

These caveats in place, a large amount can still be said about the unknown Roman soldier, those citizen soldiers of the Roman Empire. The Roman army was a formidable piece of organisation and much has found its way into the archaeological record; the huge numbers involved in the army and it logistics rendering this more or less inevitable. Britain was one of the most garrisoned of all of the provinces, de la Bédoyère (2001: 17) putting a figure of some 16,000 legionaries and the same or more of auxiliary troops in Britannia.

According to Brewer (2000: 32), legionary life included many military chores â patrols, escorts, sentries â and also those connected with the day-to-day running of the camp, such as stoking furnaces, cleaning latrines, sweeping barracks and maintaining armour: âA surviving duty-roster from Egypt, for ten days in October 87, reveals a varied existence for an ordinary legionary. One of the men listed worked in the armoury, the quarries, the baths and on the artillery, as well as doing other general duties on different days over that period.' The soldier would have to construct forts, camps and roads.

WEAPONRY

Our examination of Roman weaponry is devoted to the legionary and excludes archery and artillery. It is based on a summary of some of the material taken from the sites of forts, encampments, battlefields and a small number of stray locations. Weaponry can also be seen depicted on tombstones, sculptures and triumphal arches, and it has been recovered from sealed stratigraphic deposits.

Blade Weapons

The Roman infantryman used both dagger (

pugio

) and sword (

gladius

) against his enemies. The latter was not just a short stabbing weapon, it could be used effectively in a slashing motion, with blades of the early â up to

c.

20

BC â

gladius Hispaniensis

varying between 64cm and 69cm long and 4â5.5cm wide (Cowan, 2003a: 28). This type was replaced in popularity by the Mainz/Fulham type which was, on average, some 20cm shorter, and by the second half of the first century

AD

, by the parallel-edged, Pompeii-style

gladius

, which had a short triangular point (

ibid.

: 29).

A longer sword, the

spatha

, emerges in the late second century (Feugère, 2002: 115). These longer iron swords have been assigned a âBarbarian' origin by such authors as Feugère (

ibid.

) and were, on average, some 75â85cm long. The

spatha

made use of impressive pattern-welding technologies with a high degree of craftsmanship (Cowan, 2003b: 60). This type of sword also has a wide distribution, being found on the northern limits of Empire in Scotland (for example, the

spatha

from Newstead; Goldsworthy, 2003: 133). Although more popular in the period beyond the scope of this study, third-century wooden scabbards for these swords have been found in peat bogs in Denmark, at Vimose (Feugère, 2002: 121).

Roman swords have been recovered from varying contexts. From the battlefield site of Kalkriese, near Osnabrück in Germany, our evidence is only fragmentary, presumably as Roman weapons would have been very useful and would have been collected by the victorious German tribespeople who had destroyed Varus and his legions in

AD

9. What has been found to date includes bronze and silver mountings of a sword sheath, and âthe tip-binding for a sword scabbard, sword sheath-brackets, sheet metal at the sheath mouths, and guards â¦' (Schlüter, 1999: 138â9). These fittings would have enabled the

gladius

to have been worn by the Roman legionary on his right side and still be unsheathed quickly. Feugère (2002: 110) has detailed a number of the many sword finds throughout the Roman Empire. Handles of the

gladius

were also made from wood, and had bronze covers; a wooden pommel has been found at Vindonissa with a possible guard for this in similar material. The Royal Armouries, Leeds, has a first-century Roman sword blade that originated in Germany. This sword, which was ornately decorated with figures â perhaps the god Mars â was probably carried by a Roman infantryman, although its quality may hint at it being the belonging of someone with more wealth. Its owner also had his name engraved on the sword â Caius Valerius Primus.