The Underground Reporters (18 page)

His friend shook his head. “It is worse than you can imagine,” he said, and John’s heart sank.

It was this friend who told John about the gas chambers in Auschwitz. Thousands of Jews were herded into a large warehouse at one time, and the doors were locked. Deadly gas was then released into the warehouse. Each day, those who were sick or old or no longer needed were selected to leave their barracks for the warehouse. They never returned.

In July 1944, John’s mother was sent to the gas chambers. Even as he hugged her and said goodbye to her, she did not cry. She shared a small piece of bread with him and held him close.

That same month, John said goodbye to his father and brother, and watched them being marched out of Auschwitz on a work assignment. They each carried a small loaf of bread and a few belongings. John waved at them through the barbed-wire fence.

It was the last time he ever saw them. He later learned that Karel had fallen from exhaustion while marching on the road, and had been shot

to death on the spot. His father had refused to leave Karel’s side and had been shot next to him.

Now John was all alone. He still fought to live, day by day, with a strength he had not known he had. He went to bed each night and prayed to live to see the next day. Each morning, when he awoke, he marveled that he was still alive. But how long could he hold on?

“Did you hear the news?” someone asked. “The Allies have invaded Normandy, in France. They are moving across Europe and pushing the Nazis back.”

“I just heard a wonderful report,” someone else said. “The Nazis have been beaten in Russia, and they are starting to retreat.”

These scraps of information, whispered from prisoner to prisoner, provided renewed hope for John and the others. Maybe someday the Nazis would be defeated. Maybe someday this nightmare would be over.

CHAPTER

31

T

HE

M

ARCH

A

PRIL

1945

Day after day, news continued to trickle in that the Nazis were being driven back. The war had turned against Hitler. The Nazis knew they were about to lose the war, and they needed to hide the evidence of their crimes. John watched one day in amazement as the gas chambers of Auschwitz were torn down and destroyed.

And then new rumors started to circulate. The Nazis were moving their prisoners to camps deeper within Poland and Germany, trying desperately to evade the Allies, who were pressing closer.

In January 1945, all the able-bodied prisoners of Auschwitz were assembled in the open fields, and told that they would be leaving the camp. Along with thousands of other inmates, John was marched out of the concentration camp, and forced to march to a railway station fifty kilometers (thirty miles) away. There they boarded open coal-trains that carried them to other concentration camps.

John spent two months in a camp called Flossenburg. From there, he and the other prisoners were ordered to set out again, marching to an

unknown destination in the bitter cold, with little to eat, drink, or keep them warm. They slept in open fields and barns, huddled together for warmth. The ordeal took one hundred days, but John was hardly aware of the passage of time. The hours, days, and weeks went by in a blur. He walked automatically, placing one bleeding foot in front of the other, forcing a mechanical rhythm from his body that would keep him going. At night he closed his eyes, numb with pain, and then dragged his battered body into the cold for another day.

Many people fell ill around him. Hundreds of prisoners died each day, and their bodies were abandoned by the side of the road. John did not know how much longer he could survive. He had not eaten in days, and he had little strength. His time was running out.

One day in April 1945, just when he thought that he too might die, John looked up and saw American tanks approaching. Was this a dream? He rubbed his eyes in disbelief. With his last ounce of energy, he ran toward one of the tanks. A friendly American soldier lifted him up and handed him a chocolate bar.

The war was over.

John was alive and safe.

As soon as he was strong enough, John returned to Budejovice. He was now fifteen years old, and he was all alone. For three years he stayed in Budejovice, regaining his health. He returned to school, went to the movies, and attended concerts – all the things that had been denied to him during those long years of persecution and war.

Left: John was fifteen years old when the war ended and he returned to Budejovice. This photo was taken three months after his liberation. Right: A photo of John at the age of eighteen, taken on board the boat en route to Canada.

He was also reunited with Zdenek Svec, the Christian boy who had steadfastly remained his friend. As she had promised, Zdenek’s mother had kept the Freund family’s belongings – his mother’s fur coat, paintings, and rugs – safe during their absence. “Take them,” she urged. “They belong to you.” But to John, these things had little meaning. What good were fur coats and art? What he really wanted was his family. In the end, Zdenek’s mother gave him some money for the valuables, so he could begin to make plans for his future. In March 1948, John left Czechoslovakia, and went to a country with a strange sounding name – Canada.

Before leaving Budejovice, though, he returned for a visit to the swimming hole. He stood on that familiar piece of land, and he closed his

eyes and thought of those who were gone forever. First, he thought of his friend Beda. He could almost see him with his nose buried in a book, or contemplating his next chess move. Then he remembered Tulina, with her beautiful curls and her bright, warm smile. He thought of Rabbi Ferda, who had tried so hard to provide spiritual leadership for his community of families. And he thought of Joseph Frisch, who had been a good and dedicated teacher.

It was quiet by the river, but in his mind John could hear the sounds of his friends laughing, singing, playing sports, and talking about the newspaper

Klepy

. He could almost see Ruda Stadler seated at his typewriter in the shed, surrounded by mounds of paper, or pacing with the other editors, discussing what to include in the next issue.

The Jewish children of Budejovice had been young and healthy, with strong spirits and boundless energy. They had had a deep love for their homeland, and a strong faith in their future. They had dreamed of growing up to be doctors, writers, musicians, or teachers. It had been unthinkable to them that they might die young instead. And yet not one of them was here today.

John remembered the blood contract he had signed with his friends, promising each other that they would meet one day in the future. That reunion would never be possible. He was the only one who had returned. He stood in the center of their former playground and spoke their names aloud in a prayer to their memory. Then he turned his back and left the swimming hole for the last time.

EPILOGUE

F

INDING

K

LEPY

By the time the war ended in 1945, more than six million Jewish people had died, many of them murdered at the hands of Adolf Hitler and his evil Nazi colleagues. Of that number, it is estimated that as many as 1.5 million were children. Most of the young people who had been underground reporters in Budejovice did not survive.

Beda Neubauer went to Auschwitz, along with his parents, sister, and brother. Following the death of his parents and brother, Beda himself died in March 1944, his frail body fatally weakened by disease.

Shortly after arriving in Theresienstadt, Rita Holzer, the girl known as Tulina, was sent to the ghetto in Warsaw with her family. She died there.

Joseph Frisch, the teacher who had maintained a school for the Jewish children in his home, died in Auschwitz, along with Rabbi Ferda and most of the other Jewish families of Budejovice.

In September 1944, Ruda Stadler received his yellow deportation slip in Theresienstadt. He left Irena and Viktor behind and boarded the train for Auschwitz. From there he was transferred to another concentration

camp, where he was sent on a work detail. It was a bitterly cold day, and one of the guards at the worksite demanded the warm coat that Ruda was wearing. Ruda refused to give up his jacket. He was shot on the spot, having fought for his rights and his dignity until his last breath.

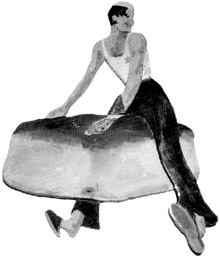

This wood carving of a strong and heroic Ruda sitting on a loaf of bread (he worked in the bakery) was done in Theresienstadt.

Irena and Viktor remained in Theresienstadt and were liberated from there at the end of the war. They were sick with typhus, a deadly disease transmitted by the lice that were rampant in the concentration camps, but they were alive.

There were others besides John who survived the war and began a new life. In July 1944, Frances Neubauer was sent to a work camp in Hamburg, where she sorted and cleaned bricks from bombed buildings, dug trenches, and built bunkers. In March 1945 she was sent from Hamburg to another concentration camp called Bergen Belsen. It was expected that she and everyone else would die there. Instead, Frances

survived, and was freed on April 15, 1945. She spent the next few months in a hospital, recovering from typhus, but with proper medical attention she slowly recovered. Years later, she married a man named Lou Nassau. They moved to Australia and had two children and three grandchildren. In 1959 she and her family moved to Palm Springs, California, where she still lives today.

Frances Neubauer in present day, standing in front of the train station across from the house in which she lived before the war.

As for John, he arrived in Toronto, Canada in 1948, and over the next years he struggled to make a life for himself in this new country. He learned English, went to school, became an accountant, married, and had three children and ten grandchildren.

Sometimes, his mind would drift back to that other place – the country where he was born, the place that held those childhood memories of the swimming hole and the creation of

Klepy

– the place where the

Nazis had taken away his freedom, imprisoned him, and killed so many of his friends and family members. It was strange to think of a place as happy and sad at the same time, but that was his memory of Budejovice – a place both joyful and tragic.