The Two of Us (14 page)

Authors: Sheila Hancock

My mother made my burgeoning career possible. Without her babysitting I could not have offered the world my definitive portrayal

of Senna, wife of Hengist Pod, inventor of the square wheel, in

Carry on Cleo

. I fear I did not always appreciate her or realise how bereft and sad she must have felt without her beloved Rick. She certainly

would never tell me. Stiff upper lip, pull yourself together, laugh and the world laughs with you, weep and you weep alone.

Weep alone I’m sure she did and I’m ashamed that I was too busy to notice or care.

9 December

Off to the Brompton. Another entry in the

Rough Guide.

A Mr Goldstraw is prepared to put a tube into his trachea

to help his breathing. The bastard thing has spread to his

windpipe. He told John straight but he just didn’t seem to

take it on board. After he left, having given us this dire

news John said, ‘I like him. He looks like Albie Finney.’

He does too.

On top of my continual television work I did plays at the Royal Court. In 1964 I turned down a part in their production of

Inadmissible Evidence

, so I didn’t meet Nicol Williamson and his best friend, John Thaw. I did do

The Soldier’s Fortune

at the Court with Arthur Lowe. The young men who ran the place were apt to rehearse all night if necessary, so great was their

enthusiasm. Arthur would flummox them by declaring, dead on five o’clock: ‘That’s it. We’ve all got homes to go to, you know.

Goodnight.’ He would have no truck with impros or political discussions and went on to give a superlative performance.

I too could tire of endless analysis. When I did a play by Edward Albee at the RSC with Peggy Ashcroft and Angela Lansbury,

Peter Hall sighed that I was like a small child splashing around in the pool while everyone else was learning to swim.

My career was a fearful hotch-potch of the serious and the trivial. No one was guiding me to plan it and I had to take everything

on offer to earn enough to support us all. My rep experience had covered such a wide range of parts and styles that it was

difficult to pin me down. I confused managements but I kept working. In fact I was working far too hard, trying to be a wife

and mother as well. And marching and petitioning and canvassing. There was much to protest about. There was the Vietnam War

and the Six Day War in Israel. The wall had gone up in Belfast. In 1969 the sixties gaiety was soured by the hideous murder

of Sharon Tate and her friends by drug-crazed hippies. Their leader, Charles Manson, called himself Jesus, and his band of

devoted disciples called themselves the Family. It was a savage travesty of our moral base lines. My concern about the state

of the world was deepened by my devotion to my child. Like my parents had for me, I wanted a safe world for her. And nice

little frocks from Biba of course.

At four years old, Ellie Jane was already fashion-conscious. I was getting ready to take her to buy her first school uniform

when my agent phoned to say that Victor Henry, the brilliant young actor who was going to play opposite me in

So What

About Love?

had done a runner. The director and the producer were keen on replacing him with a young man I knew nothing about. I’d caught

him in a military police series and he seemed all right but I’d hated him and everyone else, including Olivier, in

Semi-detached

. I said we needed a bigger name as I didn’t want to shoulder the burden of drawing an audience on my own. They said they

had tried to find someone and nobody was available. Would I at least meet him? I explained that I was rehearsing a telly series

and was snatching a couple of hours off to buy my kid’s school uniform but I’d give them ten minutes.

In the window of Biba’s beautiful new store in Kensington High Street Ellie Jane espied some red velvet pumps with diamanté

buckles. When I dragged her into Barkers, explaining that black lace-ups were better for school, she threw one of her tantrums.

She lay on the floor of the shoe department, eating the carpet and wailing that she wanted the pretty shoes. ‘

All

my friends wear red shoes to school.

All

my friends’ mummies let

them

have diamond buckles.’

People gave us a wide berth, clucking disapprovingly at my lack of control. One or two shouted, ‘Everybody out!’ I walked

away and came back a few minutes later. She was still screaming. Eventually I dumped her on my mother and, shaking and drained,

clutching my bags of uniform and food for supper, I got a taxi to the producer Michael White’s office in Duke Street.

In the cab I threw down a Purple Heart. I managed my workload only with the help of the fashionable uppers and downers. Hyped

up, I rushed in, apologising profusely. I hated being late. Michael and Herbie told me not to worry. Sitting hunched deep

in an armchair was a surly young man who said nothing. His head, resting on his hand, barely turned my way when I said ‘Hello.’

He flicked his eyes in my direction and grunted. He didn’t get up. OK, you rude little bugger. It had been a difficult day.

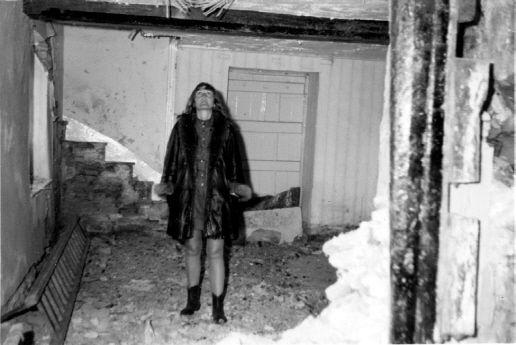

I was glad that I was wearing my full-length fox fur; it gave me confidence. I was even more glad that I had vetoed my new

up-to-the-minute maxi skirt and stuck to a mini. OK, my son, I’ll make you bloody well look at me. I moved a chair close to

him, sat down, and fixed him with a look. Crossing the best pair of legs at RADA from the knee up, I said, ‘So you’re John

Thaw are you? Well!—’

24 December

Our 28th Wedding Anniversary. After all the strife and

turmoil we have reached this complete union. I cannot, I

will not believe it will end.

Anniversary card from John.

‘My darling Sheila

,

What would I have done without you? You truly are the

love of my life. I am so proud that you stuck with me when

things were awful for you – so proud to be your husband,

lover and friend and so proud to be the father of such

wonderful and caring girls. I think it’s 28 years, but I pray

there’ll be a few more so that I can make up for this dreadful

year. If this year has taught me anything it’s that my love

for you is so deep and profound that I don’t have the words

to describe it. I must have done something right in my sixty

years to be blessed with a great woman – for that’s what

you are. I shed a tear this morning because I still can’t

believe (I suppose) that you love me as you do but I know

this – I love you every bit as much.

Your husband

John.

PS The cover of this card shows how I feel most of the

time.

THE FIRST WEEK OF rehearsal of

So What About Love?

was an unmitigated disaster. I always approach a new role convinced that I cannot play it and on the few occasions that John

Thaw looked up from his script, his expression of contempt implied that he agreed. If I suggested a piece of comedy business

in the scenes with him his silence made me feel like the cheap end-ofthe-pier comedienne I feared I was. When Herbert Wise

endeavoured to discuss the play, Anne Bell and Peter Blythe made intelligent contributions. John Thaw sighed and grunted.

The three of us agreed with Herbie that it was a slight piece that with invention and a light approach on our part could raise

a few laughs. The brooding, dark presence of the leading man in the rehearsal room was not what we had in mind. At the end

of the first week I told Herbie privately that I thought John Thaw was a mistake and he should seriously think of recasting.

Herbie assured me he was a good actor. Yes, but had he done comedy? No, not much, but he’s funny offstage. Funny peculiar,

yes. I pointed out that very few of the men I knew who were hilarious onstage were a barrel of laughs off. Indeed most, like

Frankie Howerd, Kenneth Williams and Tony Hancock, verged on the tragic. Anyway, this guy had not exactly had us falling about

in rehearsal.

25 December

Lovely family day. John was divine. We laughed about some

of the awful Christmases we’ve had. When he went to bed

the girls and I clung to each other, none of us daring to

say out loud what’s in our minds.

The following Monday the atmosphere was tense. I had spent the weekend being reassured by Alec and my mother and was determined

not to be cowed by this little upstart. In the coffee break some costumes arrived from my friend the designer John Bate for

Herbie’s approval. The fitter got me into one stunning evening dress. We loved it but there was a snag. I had to get into

it alone onstage as part of the action. The dress did up with a zip from my bottom to the back of my neck, making it impossible

to do it myself. It did, however, have a large ornate ring as a handle. I had an inspiration. John being the nearest person

to me in the rehearsal room, I told him to unzip the dress. He did, rather shakily I was gratified to notice. I then mimed

increasingly frantic writhing attempts to reach the zip, culminating in putting the ring over the door handle and doing a

ballet plié, thus pulling it up behind me. It was as yet a bit messy, but it worked. John laughed and laughed. It was a wonderful

laugh. It transformed him. His shoulders heaved, his eyes watered. He wiped them, squeaking ‘Oh God, oh dear, oh dear.’ Just

like my father.

‘It’s not that funny, is it?’

‘It is, it’s brilliant, it’s so daft, kid.’

Kid? I was nine years older than him.

I glowed at his approval. It was all the more welcome for being hard-earned. The zip business went into the show and subsequently

got a round of applause every night. Emboldened, I suggested some ideas to him in our scenes, pointing out that the script

needed all the help it could get. The respectful attitude towards writers in Sloane Square had not equipped him for the crack-papering

approach that

Ma’s Bit o’ Brass

in Blackpool had me. But Herbie was right. He was very funny offstage. In a wry, self-deprecating way. He began to make me

laugh a lot.

27 December

John says he feels the T-tube but it’s OK. I’ve had a new

mattress put on our brass bed and he’s thrilled with it. Says

he feels wonderfully comfy. Christ, with a bloody great tube

in his windpipe, how could he say that? Anyone else would

be distraught. I beg him to relax and let me love and care

for him, not to keep struggling, but it’s not his way.

Being such a small company, the four of us had many a larky supper together and often shared digs on our pre-London tour.

John had a two-seater MG and I a two-seater Morgan, so if we went for a trip during the day, we could only take one other,

and more and more it became John and I. We enjoyed each other’s company. I realised, as Peter O’Toole said later, that ‘his

features simply fell into a kind of brood in spite of him, he could be thinking of pigeon racing, anything.’ He had not been

despising me in rehearsal. Quite the opposite. He had been overawed by the expertise of the three of us and did not dare open

his mouth. Indeed, that first weekend he had nearly walked out but could tell I was nervous and did not want to let me down.

Could tell I was nervous? Could see through my bluster? Not many people did that.

He told me little about himself, but two incidents were revealing. The first happened when we were playing Manchester. We

normally went out after the show to a club-restaurant, one of the few places open late in those days. One night he tersely

said he was not coming. The next day, whereas he normally popped into my dressing room before the show to say hello, we did

not meet until our first scene and then with none of the usual jokes in the wings. He was about to leave after the show, without

saying goodbye, when I confronted him in the corridor and asked why he was being so rude. At first he denied he was behaving

oddly, but when I persisted he told me that some bloody aunt of his had left a message saying his mother would like to see

him. After a lot of probing I discovered why this was disturbing to him. His mother had deserted him, he felt nothing for

her and had absolutely no desire to see her. I was shocked by his cold dismissal. How could anyone feel like this about their

mother?

31 December

Ray over from Australia. It’s so painful for him to see his

adored brother ill. John finding it difficult to communicate

with him. Ray keeps asking questions that John doesn’t

want to answer.

I suggested it might help him to deal with it if he saw her, and came out with a lot of other half-baked psychological claptrap.

It gave me a self-righteous satisfaction when he agreed to go and meet her, but that night he curtly told me he had done as

I said, had still not liked her, and never wanted to see her again. I realised that if we were to carry on working together

amiably I could not pursue the subject further.

The second strange thing happened in Oxford. There was a very distinctive female laugh in the audience one night. I was liking

it as she seemed to get the few subtler laughs in the play. It threw John into a frenzy of rage. I extracted from him that

it was his ex-wife with whom he had just gone through an acrimonious divorce. No details were forthcoming or sought. I had

learned to let well alone. The two incidents showed an unforgiving side to his nature that I did not find attractive. In fact

it frightened me in its violence. He was not someone to tangle with. I was glad it was none of my business. There was a fear

and insecurity in him that I recognised and understood, but I could only just about cope with my own.

So we drove light-heartedly over the moors, visited galleries and enjoyed food and wine together. One day in the MG he put

on a tape of the Sibelius Fifth Symphony and I was astounded that this trendy guy in hipster velvet flares, silk shirt open

to reveal a medallion, should be so besotted with the same fuddy-duddy classical music as I. He said he loved Elgar, then

a deeply unfashionable composer. I had never met anyone so full of surprises. Nothing about him could be taken at face value.

I was sorry when the companionable tour ended and we faced the reality of London.

3 January 2002

John’s 60th birthday. We should be in Barcelona. The girls

bought us a family trip for his present, but he’s not well

enough. So we will go in April, please God – who isn’t there.

Any idea of West End theatre being glamorous in 1969 was dispelled as you entered the stage door of the Criterion Theatre.

The first hazard was climbing over the recumbent drug addicts who used the stage door entry to inject the heroin prescription

they got from the all-night Boots in Piccadilly Circus. Once inside, you descended to a gloomy catacomb where only the mice

were healthy on their diet of theatrical greasepaint, which they shared with the cockroaches. There were no windows, so the

outside world was banished once you’d descended into hell. We actors had to resort to oxygen inhalers on matinee days to keep

us bubblingly energetic for our merry romp. Unfortunately Harold Hobson, the drama critic of the

Sunday Times

, was depressed by his journey to the theatre. Part of his review was about the squalor of Piccadilly Circus, and he seemed

to blame our little play for the state of the nation. He was furious with the first-night audience for enjoying it. ‘A drawing-room

comedy for guttersnipes’ set the tone of the review.

The characters’ dalliances appalled him, as did our performances. When Sally had wanted a Hobson review for John she cannot

have foreseen it would start, ‘I awaited with dread his every entrance.’ It then went on to detail how much ‘a pretty, witty

actress’ who accompanied the critic had hated John’s performance. Hobson must have had a miserable evening, for there was

no respite when I was on, as I was ‘neither pleasing to the eye nor endurable to the ear’.

I was destroyed by his vitriol, although I did laugh at a typically high-camp letter from Kenneth Williams: ‘Poor old Hobson

seems to be in dementia and it’s reported that she’s actually dressing up as the Pope and delivering her stuff to the paper

ex cathedra.’

10 January

Read an article about me in

Time Out

full of lovely things.

What a bloody irony.

Russian Bride

, one of my best

performances ever, so I’m told, all sorts of good career

things happening, and I don’t give a sod. It means nothing.

John stumbled and fell outside the clinic. Face bleeding,

dazed, clinging to me. ‘Sorry pet, it’s my stupid foot.

Hopalong Cassidy.’ Taken in on a wheelchair. I parked the

car, pelted back and there he was laughing and joking about

it with the nurses and Jo.

John was bemused that I was so upset. He gave Hobson the Back Treatment. For him a glass was half full and all the other reviews

had been very good. But it is not easy to prance on stage the day after a review like that and convince people you are really

enchanting and funny, whatever one venerable critic thinks. John just said, ‘Fuck ’im’ and set about finding out who the ‘pretty,

witty actress’ was so that he could wreak vengeance. In her later career she never did a

Morse

or a

Sweeney

, that’s for sure. The situation was made doubly embarrassing when Hobson, who was an honourable man, was persuaded by his

fellow critics that he had maybe got things out of proportion, so he came back to re-review the play. The opening paragraph

of his second appraisal was along the lines of ‘I was right about Beckett, I was right about Pinter, but I was wrong about

Leonard Webb.’ Our unpretentious author was likened to Anouilh and I was accredited with

abattage

. As Hobson adored all things French and now, it seemed, me, I knew it couldn’t be anything to do with slaughtering animals,

as Tony Beckley gleefully maintained. Tony thought it dull when it turned out to mean ‘dynamism’, but was pleased that he

could henceforth call me Hobson’s Choice.

We settled in for a successful run. I was preoccupied with my family again, and John with his friends. During rehearsal he

had been crashing with his pal Nicol and had now moved in with Ken Parry, and was also being fed and watered by Barbara and

Ian Kennedy-Martin. It was a peripatetic existence. We saw less of each other, but on matinee days between the shows when

the sun shone, we went to nearby St James’s Park and sat in deckchairs listening to the band playing on the grandstand. Or

we had tea at Fortnum and Mason, quibbling over which was the best blend or the most tasty ice-cream sundae.

16 January

The treatment is ravaging John but he still managed a walk

in Regent’s Park. It looked glorious even in winter. I wrote

a letter to the gardeners thanking them. They probably never

hear how much comfort their work gives. We had tea at

the Langham. We do like a nice tea. When we got home

he wept with weakness, but he insists on doing these things.

For me, life was good. I was in a successful play with a congenial cast. My little house in London had been transformed by

one of my Theatre Workshop pals, Harry Green, later to become well known for do-it-yourself programmes on television. Ken

described going to a party at my house in a letter to Joe Orton: ‘What a posh place she has moved to! It’s all Scandinavia

and patio-Spanish. V. mod, I must say. I got terribly sloshed.’