The Twilight of the American Enlightenment (2 page)

Read The Twilight of the American Enlightenment Online

Authors: George Marsden

Features of the 1950s such as these provided the context for the public conversations regarding the quality and the future of American civilization that is our main focus. Most of the participants in this discussion were white male journalists and public intellectuals who commanded considerable middlebrow readership. That such cultural leadership was primarily a male activity was as much taken for granted as that “man” was the correct inclusive pronoun. Nonetheless, as had been true since the days of Harriet Beecher Stowe, outstanding women could be admitted to the club. Traditionally, cultural leaders had been overwhelmingly Protestant, at least in heritage, although recently the club doors had been flung open to include a striking number of Jews, who took leading roles in much of the conversation. The question of whether Western civilization, under American leadership, could survive in the wake of the cultural trends that had led to the Holocaust was self-evidently a most urgent question for Jews, and the

broader middlebrow readership proved ready to listen. Catholics, by contrast, only rarely gained a voice in the cultural mainstream prior to the eve of the Kennedy era.

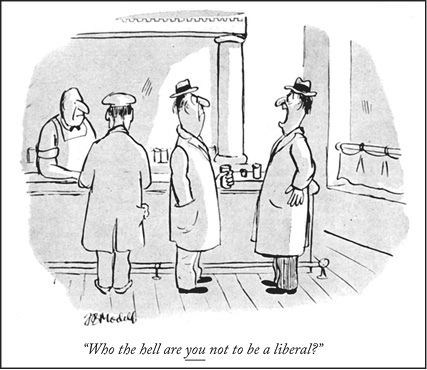

Frank Model, March 18, 1950,

The New Yorker

Most of the conversation emanated from the Northeast, to

some extent from New England but more often from New York, which was unrivaled as the nation's cultural center. The participants in the mainstream were, broadly speaking, “liberal

.” Although that term had no precise meaning at the time, in general it meant centrist: one who was neither leftist (many American intellectuals had flirted with Marxism in the 1930s, but had since repented) nor “conservative.” The most evident threat to America was the vast Soviet empire, which in its ugly Stalinist form made a consensus of liberal opposition easy to establish. The prominent literary scholar Lionel Trilling went so far as to say in 1950 that “liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition in America,” a view that gained wide assent among moderate thinkers of the day. Sometimes I refer to them as “moderate-liberal” in order to signal that I am describing a broadly shared outlook rather than any precise ideology. Whether they were Republican or (more often) Democrat, they could participate in a single national conversation based on a broadly “liberal” consensus. Their job, as they saw it, was to define on that basis where

American civilization was, and then to provide guidance as to where it should be headed.

5

One of the most fascinating

and helpful dimensions of understanding another era comes about through the process of teasing out its widely shared underlying assumptions. The dominant public conversations of each age and culture have their characteristic, shared, taken-for-granted beliefs. Certain ideals or authoritative principles can be asserted without need for real argument in any age. At the time, they may seem almost self-evident, but later generations may find them curious. Not that later outlooks are necessarily better. Rather, we should recognize that dominant outlooks may improve in some respects while the society simultaneously loses some of the wisdom or insights of the past. Nonetheless, with that reminder, we can ask about the 1950s what assumptions were widely taken for granted that might seem peculiar or questionable to most observers today.

That question brings us to the second motif and the central

interpretive argument of the book, developed most in the middle two chapters: that the underlying assumptions of the

dominant outlooks of the 1950s can be better understood if we think of them as latter-day efforts to sustain the ends of the

American enlightenment, but without that enlightenment's intellectual means. Since the word “enlightenment” as a historical term is used in many different ways, I hasten to add that

I am not using it in any technical or philosophical sense. For example, I am not using it as it was used by some European-oriented intellectuals at the time, or as it has been used by some post

modernists

in more recent years.

6

Instead, I am using it in a sense that can be easily understood in a layperson's terms: as referring to the characteristic outlook of the eighteenth

-century American founders. My argument is that the mainstream thinkers of the 1950s can be better understood if we see them as standing in far more continuity with the cultural assumptions of the founders than would be true of most mainstream thinkers today. At the same time, the discontinuities between their assumptions and those of the founders were formidable. Consequently, their hopes for providing a common ground for a cultural consensus could not be long sustained.

The American founders, men such as Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, John Adams, James Madison, and the like, took for granted that there was a Creator who established natural laws, including moral laws, that could be known to humans as self-evident principles to be understood and elaborated through reason. Most mainstream mid-twentieth-century American thinkers, who, like most modern thinkers, assumed collective intellectual progress, thought of themselves as having left such eighteenth-century enlightenment views behind. They were post-Darwinists who worked in a framework in which they took for granted human evolution and cultural evolution that shaped human beliefs and mores. They believed that societies developed their own laws, rather than discovering them in the fixed order of things. Yet, despite their modernized intellectual starting points, many of their fundamental assumptions and goals were very much in continuity with those of America's enlightened founders.

They took for granted as self-evident many of the founders'

assumptions regarding human freedom, self-determination, and equality of rights. In fact, their hopes for strengthening the American “consensus” were built around the faith that America could be united on the basis of these evolving shared ideals. They also shared with eighteenth-century leaders a confidence that rational and scientific understandings were essentially objective and therefore should be normative. Most of them believed that applying natural scientific methods and empirically based rationality to understanding society was one of the best ways to promote human flourishing. In addition, they often celebrated the “autonomous” individual, an ideal that Benjamin Franklin, for instance, would have approved. So, despite the erosion of the original premises on which the enlightenment hopes had been built, the mid-twentieth-century thinkers shared the essentials of that hope. That outlook, especially its reverence for science and the individual, was commonplace in popular and commercial culture as well.

One of the most conspicuous continuity with the eighteenth century and discontinuity with the twenty-first century

was in assumptions regarding male leadership. In the eighteenth century, “the rights of men” had meant quite literally the rights of males. By the 1950s women were included, in principle. Yet, in practice, when it came to cultural leadership, almost everyone, including most women, assumed that men would predominate. Outstanding women were welcomed here and there, but as exceptions to an assumed rule.

In practice, cultural leadership was also almost entirely

the prerogative of white men, but in the case of race, the continuities

with the American enlightenment had an important

positive effect. Race prejudice and the power of slaveholders had prevented the founders from extending the full logic of the “rights of man” to African Americans. In the 1950s, the nation was still sharply divided on that score, especially, but by no means exclusively, North and South. But most mainstream intellectuals of the moderate-liberal variety favored full equality among the races. They wished to bring the enlightenment logic of the founders to its proper conclusion.

In speaking of this dominant midcentury outlook as representing a latter-day version of the faith and hope of the American enlightenment, it is essential to be reminded of the significant place of Protestant Christianity in the American enlightenment. Unlike the French enlightenment and the French Revolution, the American Revolution involved a cordial working relationship between the dominant religious groups and most enlightened ways of thinking. In fact, a distinctive feature of the American experience was the synthesis of Protestant and enlightenment principles that one finds widely in the early republic. The colonies were overwhelmingly Protestant by heritage, and so Protestant support was of a piece with the revolutionary effort. Protestantism, even then, came in many varieties, from evangelical to liberal to

deist and nominal, but almost all of these proved adaptable to

prevailing eighteenth-century enlightened British and American assumptions. Typically, the proponents of all these forms of Protestantism saw a high regard for natural science, reason, common sense, self-evident rights, and ideals of liberty as fully compatible with their Protestant heritage. The more orthodox usually saw the truths of reason and nature and the

higher truths of faith and revelation as simply complementary. More liberal Protestants, of whom Jefferson was a prototype, had greater faith in the dictates of reason as the standard that would shape the religion of the future. Despite such differences, by the early decades of the nineteenth century, mainstream American thought, as seen, for instance, in what was taught at most colleges, was a fusion of varieties of Protestantism with various degrees of enlightenment regard for natural science, reason, and commonsense moral judgments. Almost everyone agreed that Protestant Christianity provided an important support for the principles upon which the republic had been founded.

7

Between the mid-nineteenth century and the mid-twentieth

, this fusion of Protestant and more secular principles went through a number of permutations in response to romanticism, Darwinism, pragmatism, the rise of social sciences, and a dramatic liberalization of much of mainline Protestantism (that is, the major predominantly northern denominations, such as Episcopal, Congregational, Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, Lutheran, and others), but something like the old alliance was still perceptible in the 1950s.

8

The overall cultural arrangements thus remained in continuity with the American enlightenment, particularly in the hope that a coalition of cultural leaders, including some religious leaders, despite their differences, could somehow guide the society toward a progressive, enlightened, and humane cultural consensus. Nobody thought that it would be an easy project. The founding fathers had realized that building a

coherent voluntary civilization out of many competing subgroups would

involve a tremendous balancing act. Mid-twentieth

-century leaders wrestled with American ethnic, religious, and racial diversity, the disruptions of modernity and mass culture. The immensely precarious world scene increased the difficulties and raised the stakes. Extreme McCarthyite anticommunism, anti-intellectualism, populist racism, fundamentalist religion, and just the sheer shallowness of American commercialism and popular culture made it evident that the challenges were formidable. America had been thrust into world leadership, and this role accentuated the urgency of articulating ideals that would not only help bring unity out of diversity at home, but prove worthy of respect abroad.

This brings us to the

culminating motif of the book: reflections on the implications of this history for understanding the role of a variety of religions in American culture both in the 1950s and since. This theme predominates in Chapters 5 and 6 and in the Conclusion.

The starting point for this exploration is a look at the role of the Protestant establishment in the consensus culture of the 1950s. Even though the vast majority of cultural analysis at midcentury was conducted in thoroughly secular terms, liberal Protestants retained a respected place in the cultural mainstream. Christianity, properly understood, and natural science, properly understood, the analysts typically argued, were not at odds. Rather, truths of faith and truths of science were complementary in that they dealt with two different realms of human experience. On such a basis, Protestant theologians, of whom Reinhold Niebuhr was the best known,

could be prominent voices within the liberal mainstream. In Niebuhr's case, his chastening words regarding the human condition could be welcomed, but his generalized Christianity offered little to challenge most of the secularizing trends that he himself identified.

When the consensus culture collapsed in the 1960s and 1970s, taking with it all but the vestiges of the old Protestant establishment, that collapse initiated, among other things, a religious crisis.

9

Formal recognition of Christianity, as in public school prayers and observances, declined at the same time. There were tumultuous changes in mores and a questioning of the shared patriotism that had characterized the 1940s and

1950s. This combination led at first to a cultural backlash, and

then, by the later 1970s, to the rise of the religious right and the initiation of the culture wars. Although I do not attempt a full account of these developments here, I do offer an overview to illustrate how they may be illuminated by viewing them in the context of the demise of the consensus culture of the 1950s and the rise of the idea of taking back America by restoring a lost “Christian consensus.”