The Twilight of the American Enlightenment (15 page)

Read The Twilight of the American Enlightenment Online

Authors: George Marsden

Niebuhr's popularity in the liberal-moderate mainstream of the 1950s was heightened by his insightful book

The Irony of

American History

. Appearing in 1952 when McCarthyism was at its height, when the United States was still fighting in Korea, and when the conflict with communism and the Soviets was being described in simple black-and-white terms, Niebuhr's analysis seemed like a breath of fresh air. He could speak with

a degree of moderation because he was already established as firmly anti-Communist and known for his “realism” in foreign policy, especially his argument that force must be met with force

.

Yet even though Niebuhr deplored Soviet totalitarianism, he also pointed out what to many readers was an illuminating insight: that the United States had more in common with the Soviet Union than either would be willing to admit. Each affirmed the goal that humans should be masters of their own destinies. Each believed that the prescription for reaching that goal involved following the dictates of an economic system. Each had a myth of its own innocence and of the corruption of its opponents. It was particularly ironic that while Americans saw their prosperity as evidence of God's favor and hence of their own virtue, their enemies saw Americans' riches as evidence of their vice. Americans were fond of condemning the Soviet Union's “materialism,” Niebuhr observed, “but we are rather more successful practitioners of materialism as a working creed than the communists, who have failed so dismally in raising the general standards of well-being.” Each nation saw itself in the forefront of modern progress based on the highest intellectual authority: the scientific analysis of social conditions. Each was a latter-day manifestation of the enlightenment faith in the ability of science and rationality to solve

human problems. Each nation continued to have an almost unreserved regard for the scientific model as the key to controlling and improving the human condition.

16

In detailing the American version of naïve faith in the natural scientific method for engineering social progress, one of Niebuhr's favorite targets was John Dewey. According to Niebuhr, Dewey was just the most prominent priest in a widespread cult of faith in human intelligence. In

The Irony of American History

, Niebuhr quoted a letter to the journal

Science

in which an unnamed writer deployed a common argument of the day, that “if men can come to understand and control the atom, there is reasonable likelihood that they can in the same way learn and control human group behavior.” Niebuhr saw such assumptions as pervading the social sciences, and he had long regarded Dewey as one of the most influential purveyors of the false hope that the scientific method that worked so well for understanding nature was therefore the best guide for human behavior.

17

Niebuhr's critique of faith in the ability of human intelligence to control history was based on an essential distinction, or dualism, in his thought between the realm of nature and

the realm of history. Nature was the realm of necessity and was

therefore susceptible to scientific investigation and control. But history was the realm of freedom as well as natural causes. Even at the level of natural causation much of human behavior was insusceptible to prediction and control, because causal chains were operating simultaneously at so many levels:

“geologic, geographic, climatic, psychological, social, and personal.” In addition, and more importantly, “human agents

intervene unpredictably in the course of events,” and even when they were just trying to observe events, they remained as interested actors. Human self-interested perversity could also subvert the best-laid prescriptions. One only had to witness the Soviet Union to find the outstanding examples of this human inability to manage history according to a scientific scheme. Pragmatic American social scientists were preferable in that they rejected global ideologies, and their methods yielded some real benefits. Yet, as humans characteristically did, they overestimated the relatively good. Hence, their belief that the scientific method was the key to resolving human social and political problems was ultimately naïve.

18

The intensity of Niebuhr's disagreement with Dewey and pragmatic social scientists is best understood as, in a sense, a family quarrel. Niebuhr, too, was an avowed pragmatist. He had been deeply influenced by William James, and he broadly followed James's method of preserving a realm of freedom above the determinism of mere nature. In typical pragmatist fashion, Niebuhr held that “things and events are in a vast web of relationships and are known through their relations.” Trying to understand reality in all its relationships helped him guard against ethics that absolutized the relative. Niebuhr was instead characteristically occupied with discovering the relatively best solutions that lay between extremes. Like James, but unlike Dewey, Niebuhr believed that the meaningful relationships in reality included religious experiences and categories that went beyond nature alone. These theistic perspectives were essential to determining one's ideals and also to appreciating one's limitations in meeting those ideals. Unlike James,

Niebuhr drew on explicitly Christian theological categories that emphasized human finitude, sinfulness, and dependence, and so he was critical of James's optimism. Furthermore, and very much like Dewey, Niebuhr went beyond James's individualism and applied the pragmatic method to the project of establishing an American social ethic. Yet he had a sharp falling out with strictly secular pragmatists who followed Dewey in believing that modern science could provide the highest authority for constructing such a social ethic.

19

Niebuhr made sure to emphasize that he did not reject natural science or the natural scientific method as such. Like many mainline Protestants of the generation that had witnessed the Scopes trial of 1925, he was at pains to assure his readers that, whatever his critiques of naïve liberalism, he was not anything like a fundamentalist. “If we take the disciplines of the various sciences seriously, as we do,” he affirmed, “we must depart at one important point from the biblical picture of life and history.” In positing a dualism between nature and freedom, Niebuhr was conceding that the realm of nature was determined, and hence that the dictates of natural science indeed reigned supreme there. “The accumulated evidence of the natural sciences convinces us that the realm of natural causation is more closed, and less subject to divine intervention, than the biblical world view assumes.” Accordingly, “we” [meaning sophisticated moderns] “do not believe in the virgin birth, and we have difficulty with the physical resurrection of Christ. We do not believe, in other words, that revelatory events validate themselves by a divine break-through in the natural order.” Contrary to those who took the Bible literally,

Niebuhr argued that the truths of revelation were better understood simply as essential verities, rather than on the basis of historical facts validated by miracles. The truth of the revelation of the fall of humanity, for instance, was too profound to be dependent on belief in literal events in the Garden of Eden. The same would apply to other biblical doctrines. They had some relation to history in that they fit human experience, but they were not dependent on biblical claims of literal divine interventions in the course of nature.

20

Niebuhr thus was careful to grant scientific outlooks sovereignty in their own territories, even as he resisted imperialistic efforts to reduce human experience to naturalistic terms. Such scientific imperialism failed to take account of the realm of freedom in human history, the realm in which genuine encounters with God were possible. Niebuhr had thus reserved a place in modern culture for what he regarded as the essence of Christian faith, a place that would be safe from the onslaughts of scientific naturalism. Within that sanctuary, one could benefit from scientific findings and use reason as well as the history of human religious experience as a guide for identifying the best of shared human insights into the divine. Yet how one interpreted or chose among those insights also depended to a degree on subjective human experience.

The grand irony of that strategy was that, while Niebuhr himself used it effectively as a way to preserve a public role for the Christian heritage, its subjective qualities made the faith wholly optional and dispensable. As atheists for Niebuhr evidenced, one could simply bypass the theology and adopt the profound insights into human limitations that Niebuhr

offered.

21

Niebuhr was remarkable in that he was a Protestant theologian who could speak to a wide swath of American liberal culture. Yet he was also speaking at the end of the Protestant era, and for all his brilliance was like a candle that burns brightest just before it goes out.

Although Niebuhr's insights

had significant impact on cultural leaders here and there, his sort of theology could not even begin to deflect one of the most conspicuous forces of his era, a force that he himself identifiedâmodern culture's growing secularity. In 1957, for the one hundredth anniversary issue of

Atlantic Monthly

, he described those forces with characteristic perceptiveness in an essay on “Pious and Secular America.” The United States, he observed, was “at once the most religious and the most secular of Western nations.” His question was, “How shall we explain this paradox?”

In answering this question, Niebuhr distinguished two very different sorts of forces shaping America's burgeoning modern secularity. One kind of secularity was “a theoretical secularism which dismisses ultimate questions about the meaning of existence, partly because it believes that science has answered these questions and party because it regards the questions as unanswerable or uninteresting.” The other secularizing force was “a practical secularism, which expresses itself in the pursuit of the immediate goals of life,” and which America's detractors characterized as “materialism.” That second kind of secularity arose from “our passion for technical efficiency,” a passion that, when combined with abundant natural resources, provided America with a cornucopia. Although American piety had always had some impact on American political culture, it had had almost no impact on its economic culture, where the demands of efficient technique overwhelmed all else.

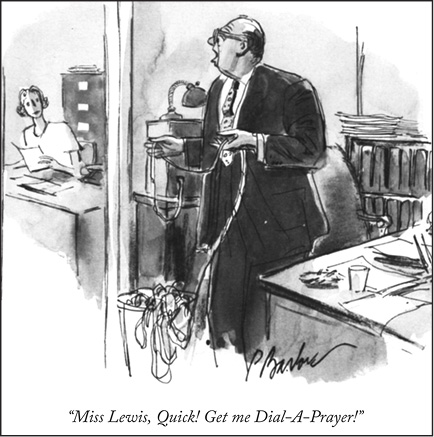

Perry Barlow, March 5, 1960,

The New Yorker

Niebuhr thought both kinds of secularity could be compatible with religion retaining a real place in American life. Ever since the American Revolution, the secular heirs of the enlightenment and the religious heirs of frontier revivalism had been able to agree on many shared ideals, even if most of these involved a shared naïveté and optimism regarding human abilities. And in the contemporary world crisis, it was not hard to see the limits of “the enlightened mind,” and the fact “that great technical power cannot solve these ultimate problems of human existence.” Hence, Americans were finding that “the frame of meaning, established by the traditionally historic

religions, has become much more relevant to the modern man than seemed possible a century ago.” Underneath all the prosperity and expressions of confidence was an emptiness. “Our gadget-filled paradise suspended in a hell of international insecurity,” he proclaimed in a particularly arresting phrase,

“certainly does not offer us even the happiness of which the former century dreamed.” Niebuhr believed that most of the

revived religion of the day did not adequately face this reality, but he also thought there was still hope that a gospel that was more realistic about human limitations might prevail. So, he continued: “Only when we realize these disappointed hopes can we have a truly religious culture. It will probably disappoint the traditionally pious as much as the present paradise disappoints the children of the Enlightenment.”

What is striking in this essay is the disparity between the profundity of the diagnosis and the superficiality of the prescription. In part that may be attributed to the popular nature of the article, but it also is revealing of the problem of a lack of a source of authority to which to appeal beyond the weight of Niebuhr's own insights into selected biblical themes. So he concluded his account of how America might find a “truly religious culture” with an appeal only to a “piety [that] will have recaptured some of the characteristic accents of the historic religions.” But this recapturing, he made clear, would also alter those religions. Tellingly, he spoke of them in the past tense. “The great historic religions, in short,” he declared in his culminating sentence, “were rooted in the experience of

the ages so that they could not be deluded by the illusions of a

technical age.” Niebuhr was pointing to some sort of higher

synthesis of the greatest principles from higher religious heritages as the last best hope for an improved American faith. He was not as optimistic as Henry Luce, but he, too, was proposing a modernized theism, even if a chastening theism. No more than Luce did he offer any suggestion as to how such a higher theology might even begin to gain currency sufficient to counter the secularizing trends that he had identified with such insight.

22