The Triumph of Seeds (7 page)

Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

Diamond has argued that the presence of readily domesticated grasses gave the Mediterranean region an environmental edge, helping its people develop early and dominant civilizations. The relative scarcity of such grains in parts of Africa, Australia, and the Americas may have delayed their journey toward agriculture, a hindrance with significant consequences for their later interactions with European and Asian cultures. Regardless of when the transition took place, however, those fundamental links between grass and civilization have never gone away. Once established as the basis of our diet, grains became thoroughly enmeshed in economies, traditions, politics, and daily life around the world. Any examination of history quickly finds grain at the root of transformational events.

In the latter days of the Roman Republic, city leaders pacified a restive public through lavish entertainments and free or heavily subsidized allotments of wheat, a strategy of diversions that Juvenal famously dubbed “bread and circuses.” First codified by the Grain Law of Gaius Gracchus, grain subsidies continued for centuries as an important political tool throughout the empire. A goddess, Annona, was specifically invented by the state to personify the grain dole. She often appeared in statuary and on coinage, holding sheaves of wheat and perched on the prow of a ship to symbolize the steady arrival of grain into the capital. While historians attribute Rome’s ultimate demise to everything from inflation to the mental-health drawbacks of lead plumbing, no one disputes that grain shortages hastened its fall. Long dependent on imports from North Africa, Rome first saw Egyptian production diverted to Constantinople, and then lost the rest of its supplies when Carthage fell to the Vandals.

Prices skyrocketed, and major food riots and famines rocked the capital at least fourteen times in the fourth and fifth centuries. When the Visigoths laid siege to Rome in

AD

408, the grain dole was cut in half and then to a third before the city was finally overrun. As two noted historians put it, “bread, or the lack of it, had finally

destroyed the Western Empire.”

F

IGURE

2.2. Invented to embody the annual gift of grain from government to citizens, the goddess Annona was an early example of Roman propaganda. These coins, from the third century

AD

, show her holding grain sheaves and a cornucopia. On the left, her foot rests on the curved prow of an incoming grain ship; on the right she stands beside an overflowing

modius

, the basket used to dole out individual shares. P

HOTO

© 2014

BY

I

LYA

Z

LOBIN

.

When the Black Death raged through Asia and Europe in the fourteenth century, a baffled and terrified populace blamed it on everything from earthquakes to acne. Only later did epidemiologists trace the disease to tiny fleas inhabiting the

fur of the common black rat. But even this insight failed to explain the plague’s spread. After all, the average rat travels only a few hundred yards from its birthplace over the course of a lifetime, so how did the illness move from China to India and the Middle East and all the way north to Scandinavia in a matter of years? The answer lies not in the ranging habits of rats, but in their diet. While black rats will eat almost anything, they thrive on grain of all types and travel with it wherever it goes. And while most fleas live only a matter of weeks, those found

in rat fur can persist for a year or more, and their larvae have learned to eat grain. So even on a long ship voyage, when all the plague-sick rats might die at sea, the fleas survived (with their offspring happily munching away in the hold), ready to infect new rats and people at every port of call. And though a fastidious overland merchant might rid his caravan of rats, there again were the fleas, safely tucked away in every bushel of grain. At its peak, the plague’s rapid spread suggests that it must have become airborne—transmitted directly between people through coughing and sneezing. But historians still believe it got its start with the grain trade, skipping only the remotest backwaters, or kingdoms like Poland that kept their borders firmly closed. Periodic outbreaks continued until well into the twentieth century, striking places like Glasgow, Liverpool, Sidney, and Bombay—all of them busy ports with an active commerce in grain.

The history of revolts and uprisings also turns on grass, with grain shortages often providing the spark that transforms resentments into open rebellion. When fourth-century Chinese emperor Hui of Jin was told that his subjects were starving for lack of rice, he reportedly asked, “Then why don’t they eat meat?” Subsequently, Hui lost half his kingdom in the Wu Hu Uprising. And though historians doubt that Marie Antoinette ever said, “Let them eat cake,” no one questions that wheat and bread shortages helped spark the French Revolution, the Russian Revolution, and the Spring of Nations in 1848, a conflagration that affected fifty countries in Europe and Latin America. The trend continues to the present day. It is no coincidence that the Arab Spring began in Tunisia, the world’s largest per capita wheat consumer, in a year following heat waves, floods, fires, and crop failures in some of the world’s top wheat-producing nations. Tunisian wheat imports dropped by nearly a fifth in 2011, prices spiked, and widespread food riots swept the country in the months leading up to the revolution. Protests and riots over grain prices also preceded the rebellions in Libya, Yemen, Syria, and Egypt, a country where the word

aish

means both bread and life. The Algerian government, in contrast, responded to the food crisis with

a massive investment in grain,

increasing

wheat imports by over 40 percent in 2011, stabilizing prices, and constructing huge storage facilities to stockpile against future shortfalls. Though unrest continues to sweep the region, and bread riots rocked the new Egyptian government in 2012, the Algerian regime still stands.

Of course, no single factor led to the Arab Spring, but the underlying role of wheat prices brings grain politics full circle. More than 10,000 years after the hunter-gatherers at Abu Hureyra first turned to farming, the grasses they helped domesticate continue to shape history. The legacy of the gatherers is profound. In the Fertile Crescent and around the world, access to grain plays a subtle but pervasive role in the fate of nations: when harvests are poor, governments falter. (The same cannot be said about the legacy of the hunters. No empire has ever collapsed from a shortage of antelope.) But it doesn’t take a revolution or a plague to see the influence of grass seeds on modern life. Nothing reveals their role in our culture more vividly than a visit to grain country at harvest time.

“Y

ou’re looking at 2 million bushels of soft wheat,” said Sam White. We were perched on the back of his pickup truck, peering in through the door of a cavernous building heaped to the rafters. Cool, dry air drifted over the sea of grain and brushed past our faces. I did some quick math. With prices hovering around nine dollars a bushel, the wholesale value of this one storage depot exceeded $18 million. Processed into flour and packed into five-pound bags, it would bring over $100 million at a grocery store. Bake that flour into bread, pretzels, Pop Tarts, Oreos, or any of the thousands of other wheat-based products, and the bill at checkout would rise still higher. Before Sam rolled the big door closed, I raised up my camera and snapped a picture, but it didn’t turn out. The grain just looked like a pile of sand; there was nothing to show that it stood three stories tall and stretched the length of two football fields. Nor could a photograph explain that hundreds of similar sheds and silos dotted the landscape in all directions, every one of them filled to the brim.

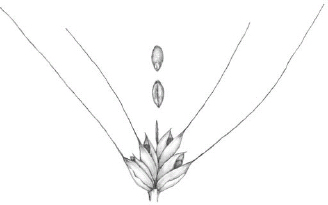

F

IGURE

2.3. Wheat (

Tricetum

spp.). Descended from wild grasses native to the Middle East, wheat now covers more agricultural acreage worldwide than any other crop. Like the individual grains of other edible grasses—from rice and corn to oats, millet, and sorghum—each tiny grain of wheat is actually a complete seed-like fruit called a

caryopsis

. I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

Anyone biting into a crusty baguette or twirling spaghetti noodles onto a fork has some vague notion that their meal began life on a farm. But few of us stop to consider the daunting logistics that lie between field and marketplace. The grain in Sam’s barn was valuable, but the padlock on the door seemed superfluous—after all, who could possibly steal something that weighed 60,000 tons? Storing, processing, and moving grain on that scale requires infrastructure, and it was exactly that system of silos, trucks, roads, railroads, barges, and oceangoing freighters that I had returned to the Palouse to learn about.

“All the wheat is in now,” Sam told me as we climbed back into his truck. “Barley too.” My guide for the day, Sam White worked in upper management at the Pacific Northwest Farmers Cooperative, a group of 800 growers who co-own twenty-six storage and processing facilities in and around the small town of Genesee, Idaho

(population 955). He grew up farming, but switched to the business side of things after college, and has now spent more than two decades selling Palouse grain in a complex global marketplace. Stocky, with sandy hair and a sun-weathered face, Sam likes his job: helping local farmers get the best prices for their crops. Not that it’s always easy. “In my dad’s time, if the price per bushel changed two cents in a year, that would be a big deal. Now you can see it swing thirty or forty cents in a day.” On top of that, farmers form strong bonds with the crops they’ve worked so hard to nurture, and often let emotions cloud their business sense. “Frankly,” he confided, “it’s usually better if their wives decide when to sell.”

We drove out of town between rolling fields of bright blond stubble lined with the tracks of combines. I smiled as we passed familiar prairie eyebrows, their coarse grasses and shrubs framing the hilltops like bushy parentheses. There was a wildfire burning in the nearby Bitterroot Mountains, and its smoke mingled with the dust billowing up behind distant tractors. It hadn’t rained for months, but the fall planting was already well underway. Here and there, newly plowed fields stood out—broad swathes of dark earth awaiting their allotment of seed. Sam told me about tilling methods, fertilizers, and crop rotations, and then turned back to commerce: “Over 90 percent of what we grow here ends up in Asia,” he said. That statistic surprised me, but it made perfect sense. Because in spite of its location, totally landlocked and more than 350 miles from the coast, the Palouse lies only a few minutes from a seaport.

Sam steered the truck onto a busy highway and we soon began heading sharply downhill. Every year, millions of tons of Palouse grain follow the same route, descending into a steep-walled canyon where the Clearwater River joins the Snake River at the town of Lewiston. There, we stood beneath towering concrete silos and a huge conveyor belt that cantilevered out over the river. It clanked and whirred above us, dropping a steady flow of wheat into the hold of a waiting barge. Golden chaff drifted through the air all around, glinting in the sunlight and settling like flotsam on the calm water.

“It takes three or four barges to make a tow!” Sam shouted above the noise, and went on to explain how the grain would make its way down the Snake and Columbia rivers all the way to the Pacific Ocean. Lewis and Clark traveled this same path in the early nineteenth century, but where the famed explorers navigated swift currents and treacherous rapids, modern vessels move through locks and dams and what is essentially a series of long, linear lakes. When journalist Blaine Harden boarded a tug to make the journey in the mid-1990s, his captain offered a sober prediction: “By the time you get to Portland, you are going to be

bored shitless.”