The Triumph of Seeds (28 page)

Read The Triumph of Seeds Online

Authors: Thor Hanson

Tags: #Nature, #Plants, #General, #Gardening, #Reference, #Natural Resources

With a wingspan stretching to eighteen inches (forty-five centimeters), the great fruit-eating bat has more than enough flapping power to carry off

almendro

seeds. In flight, those huge wings make its four-inch (ten-centimeter) body look like an afterthought—just enough bones and skin to hold on to a heavy load. While fruit-eating bats often dine on figs, flowers, or pollen, the pile before us proved that

almendro

was something special—for the bat, and for the tree itself. Unlike squirrels and agoutis, who eat and destroy any seed they don’t misplace, the fruit-eating bat’s interest is entirely eponymous. It wants only the thin, watery flesh that surrounds the shell. Perched upside down, with sharp teeth working furiously, a bat can scrape away the pulp from the husk in minutes, dropping the seed unharmed to the forest floor below.

To me, eating

almendro

fruit was like gnawing on a bland, over-ripe snap pea, toughened by sun. But for the bat (or bats) that had roosted here, it was a taste sensation worth thirty round-trip flights. And worth the risk of returning again and again to a tree where owls, bat falcons, and pythons lurked, waiting specifically for an opportunity to snatch the unwary visitor. That element of danger played a vital role in the system. Without it, the bats would simply lounge in the

almendro

itself, gorging on fruit and dropping the seeds directly below the mother tree—unharmed, but undispersed. (Monkeys do exactly that during the daylight hours, as do smaller bats incapable of lifting the heavy fruits.) But so long as predators staked out the trees, any bat large enough would carry its prize away to the safety of a feeding roost, creating a pattern of seed dispersal so distinctive that José and I came to know these bats’ every move, without

ever laying eyes on one.

I glanced again at the empty palm leaf above us before we walked on. It was a familiar sight. To confirm our hunch, we had looked up in exactly the same way nearly 2,000 times, comparing the locations of palm leaves to the locations of seeds. Whether we found them singly, in pairs, or in troves like this one, our largest yet, the dispersed progeny of

almendro

were twice as likely to lie beneath a bat roost.

(The bats chose palm fronds for good reason: the drooping leaflets hid them from predators above, while the long, spindly stalk would shake with warning if anything tried climbing up from below.) This pattern held everywhere we looked—in isolated patches as well as large swathes of virgin forest. Back in the lab, genetic fingerprinting

helped me take the data further. By tracking particular seeds from tree to roost, I could show that a bat would fly almost anyplace that an

almendro

came into fruit. Even trees stuck in the middle of pastures were part of the network, attracting hungry bats and co-opting them into carrying their seeds to better habitat thousands of feet away. With large rainforests disappearing, our results gave me hope that

almendro

—and the many species that depended on it—could persist in this new landscape of fragments, farms, and pastures.

Hiking back along our transect, we passed suddenly into blinding sunlight where the forest ended in a straight green line. Rank grassland stretched away over rolling hills dotted with remnant trees, some of them

almendro

. We knew the area well and weren’t surprised to see the landowner, Don Marcus Pineda, leading a donkey across a nearby field. He waved and turned in our direction. Pineda owned a lot of property and still worked it himself, clearing trees, mending fence lines, and tending a large herd of beef cattle. As he neared, I smelled something chemical from the sloshing yellow jugs strapped to the donkey’s packsaddle. Pineda told us he was heading out to spray some bracken, a prolific, inedible fern he wanted gone from his rangeland. But we knew there was more news, or he wouldn’t have gone so far out of his way to greet us. Finally, he spoke again.

“El Papa ha muerto,”

he said simply—“The Pope is dead.” Marcus Pineda lived on a rugged frontier farm near the Nicaraguan border, and had always struck me as machismo personified—a tough, lined face squinting out from beneath his ever-present cowboy hat. But it was obvious this loss had hit him hard, and it shook José, too. For several minutes the three of us stood together quietly, heads bowed in the muggy heat. Pope John Paul II had been a hero in Costa Rica, where over 70 percent of the population identified as Roman

Catholic. But he was more than a religious leader. His frequent trips to Latin America, his personal charisma, and his genuine interest in the region made him a beloved figure both inside and outside the church.

As a scientist, I, too, felt a fondness for John Paul. After all, he was the pope who finally pardoned Galileo, and he did more than any of his predecessors to reconcile church teachings with the theory of evolution. In discourses to the Pontifical Academy of Science, he had called Darwin’s ideas “more than a hypothesis,” and had gone so far as to imply that the Book of Genesis was allegorical, and not “a scientific treatise.” His words to the academy were brief, but if John Paul had spoken at length, he might have pointed out any number of metaphors in Genesis, many of them biological. The chapters concerning Adam and Eve, for example, do more than describe the dawn of humanity and original sin. They also tell one of the greatest seed dispersal stories of all time.

From the Renaissance forward, artists have made the scene indelible: Adam and Eve sharing a luscious apple below the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, with a serpent coiled around the closest branch. Botanical purists point out that such large-fruited apple varieties didn’t become common until the twelfth century, and that the fruit should probably be a pomegranate. Whichever the species, the cunning snake had chosen a perfect lure, something that evolved for the sole purpose of temptation. To a hungry animal, the tiny pips inside an apple or the stone at the center of a date may seem irrelevant, secondary to the irresistible flesh. But the truth is the other way around. Fruit, in all its magnificent variety, exists for no other reason than to serve the seeds.

Whether a plant is growing in the Garden of Eden, in a tropical rainforest, or in a vacant lot, its investment in producing, nourishing, and protecting its seeds means nothing without dispersal. Offspring that languish on the mother or drop directly below amount to little more than a wasted effort. If they sprout at all, they won’t survive long in the shade of a fully grown parent. (In some cases, adults release toxins into nearby soil to prevent their progeny from becoming competitors.) For

almendro

, adding a thin layer of pulp to its seeds can entice fruit bats to carry them half a mile or more. The Tree of Knowledge did even better. According to Genesis, eating that Forbidden Fruit resulted in Adam and Eve’s immediate expulsion from Eden. Metaphorically, at least, the fruit went with them. Some depictions show the guilty couple still clutching a half-eaten apple. And if it was indeed a pomegranate, then the seeds would have been safely lodged in their digestive tracts. Either way, the Tree had put itself in a great position. With that one tempting fruit, it went from a garden-bound existence to the promise of mass dispersal with humanity across the face of the earth.

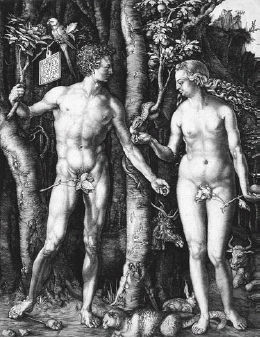

F

IGURE

12.1. Albrecht Dürer’s 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve has it all—fig leaves, a tree, a snake, and the ultimate sign of temptation: fruit.

Adam and Eve

, Albrecht Dürer, 1504. W

IKIMEDIA

C

OMMONS

.

Much has been written about the relationship between people and fruit or other crops—the way we take them with us wherever we go. Apples alone went from a single species domesticated in the mountains of Kazakhstan to thousands of varieties—people grow them on every continent outside Antarctica. It’s only a slight exaggeration to call us servants of our food plants, diligently moving them around the world and slavishly tending them in manicured orchards and fields. And it’s no exaggeration at all to call this activity seed dispersal. We do it as unconsciously as the bats do, living out an interaction between plants and animals that is nearly as ancient as seeds themselves. Fruit influences our behavior because it evolved to do so; developing flesh we find sweet and colors and shapes that attract our attention. Its power reaches beyond our farms and kitchens, touching beliefs at the boundary between culture and imagination. Look no further than the glut of grapes, pears, peaches, quince, melons, oranges, and berries festooning every basket and platter in the history of still-life art. Our desire for fruit makes it more than a symbol of temptation—it helps us to define beauty itself.

In nature, fruit is typically both delicious and fleeting, traits that help it attract just the right dispersers at just the right moment. People generally seek out sweetness, but plants can readily develop fruits to please other palates, producing proteins and fats as well as sugars. The rich packets adorning castor beans (and a host of other species) are designed to

attract otherwise carnivorous ants, while the Kalahari Desert’s

tsamma

melon, ancestor to the watermelon, draws in all comers by satisfying a universal hot-country yearning: thirst. In any case, the desired flavor appears only as the seeds mature and prepare for departure. Before the seeds ripen, plants keep animals at bay with fruit that is bitter or downright poisonous. The physician who accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second voyage observed a group of sailors on the beach happily tucking into what appeared to be wild crabapples. “But no sooner did they taste them than their faces swelled, growing so inflamed and painful that they almost

went out of their minds.” The men survived, but had probably been trying to eat

manzanillo

, a fruit the local Carib Indians harvested for making arrow poison. It remains toxic even when ripe, perhaps as a deterrent to insects or fungi, or to ward off all but a specialized

(and as yet unknown) seed disperser. Poisonous, single-species strategies are unusual, however. Most fleshy-fruited species take the route of the apple, luring potential dispersers with something as widely desirable as the plant can afford to produce.

F

IGURE

12.2. Apple (

Malus domestica

). An iconic symbol of temptation in everything from artwork to Bible stories to

Snow White

, apples play a role uniquely suited to fruit. In nature, fleshy fruits of all kinds evolved for the sole purpose of tempting animals into dispersing the seeds of plants. I

LLUSTRATION

© 2014

BY

S

UZANNE

O

LIVE

.

“Affordability” may not sound like a botanical term, but balancing the household budget dominates the lives of plants. Energy, nutrients, and water are the coins of the realm, limited resources that must be divided among vital priorities. Spending a fortune on dispersal runs the risk of shortchanging the seeds’ nourishment or protection, not to mention the growth and defense of leaves, stems,

and roots. In the world of plant economics, producing fleshy fruit is costly. Gardeners and farmers know this from experience—the “heavy feeders” in any vegetable plot always include the large-fruited crops like tomatoes, melons, squashes, eggplants, cucumbers, and peppers. Adding fertilizer or a scoop of compost tilts the balance, helping these species invest more in the production of something succulent. In the wild, plants scrape by with whatever the local soil and weather provide. But even in a good year, the huge expenditure of fruiting almost always makes the season brief, only adding to its cachet.

As one of the rarest, sweetest, and most nutritious things in the landscape, ripe fruit can draw animals from far and wide. African elephants trek miles out of their way to find favorite species like bitterbark, an odorous, cherry-sized fruit native to the Congo basin, or

marula

, a southern African delicacy related to mangos. In one forest, researchers mapped a network of elephant trails connecting every known adult of the

balanites

tree, even though it only bore fruit every two or three years. Our own species also goes to great lengths to take advantage of a wild harvest. Traditional San tribes-people in the Kalahari base their travel routes and seasonal encampments around the availability of

tsamma

melons, just as Australian Aboriginals in the Western Desert once did with figs, wild tomatoes, and

quandong

, a peach-like member of the sandalwood family. It’s not uncommon for similar fruit interests to put people and wildlife in direct competition. Friction between villagers and mountain gorillas in Uganda increases during

omwifa

season, when both apes and local residents hone in on the same wild groves to harvest the tree’s lumpy, aromatic fruits.