The Triangle Fire (3 page)

Authors: William Greider,Leon Stein,Michael Hirsch

ILLUSTRATIONS

1. The Asch building housing the Triangle Shirtwaist Company

2. Water being poured into the Asch building

3. Bodies laid out and tagged on the sidewalk

4. Three officers carrying personal effects

5. Friends and relatives identifying bodies in Pier Morgue

6. Crowds outside the Asch building

7. A room in the Asch building after the fire

8. Joseph Zito, the heroic elevator operator

9. Coroner and jury questioning employees

10. Thousands awaiting the funeral procession

11. A description of the disaster in a local newspaper

13. One of hundreds of families in mourning

14. Cartoon from the New York

Evening Journal

, March

31, 1911

All of the photographs in this book are from the UNITE Archives in the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 14853-3901. We are especially grateful to Barbara Morley for assistance with the selection of the photographs and with the captions.

For a website on the Triangle fire, see

http://www.ilr.cornell.edu/trianglefire

.

For a website on sweatshop issues, see

http://www.behindthelabel.org

.

PART ONE

1. FIRE

I intend to show Hell.

—

DANTE

:

Inferno

,

CANTO XXIX

:96

The first touch of spring warmed the air.

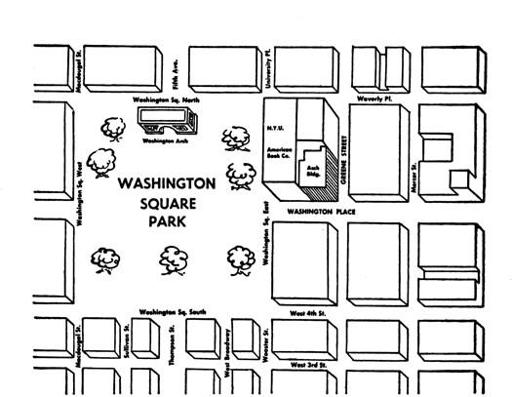

It was Saturday afternoon—March 25, 1911—and the children from the teeming tenements to the south filled Washington Square Park with the shrill sounds of youngsters at play. The paths among the old trees were dotted with strollers.

Genteel brownstones, their lace-curtained windows like drooping eyelids, lined two sides of the 8-acre park that formed a sanctuary of green in the brick and concrete expanse of New York City. On the north side of the Square rose the red brick and limestone of the patrician Old Row, dating back to 1833. Only on the east side of the Square was the almost solid line of homes broken by the buildings of New York University.

The little park originally had been the city’s Potter’s Field, the final resting place of its unclaimed dead, but in the nineteenth century Washington Square became the city’s most fashionable area. By 1911 the old town houses stood as a rear guard of an aristocratic past facing the invasions of industry from Broadway to the east, low-income groups from the crowded streets to the south, and the first infiltration of artists and writers into Greenwich Village to the west.

Dr. D. C. Winterbottom, a coroner of the City of New York, lived at 63 Washington Square South. Some time after 4:30, he parted the curtains of a window in his front parlor and surveyed the pleasant scene.

He may have noticed Patrolman James P. Meehan of Traffic B proudly astride his horse on one of the bridle paths which cut through the park.

Or he may have caught a glimpse of William Gunn Shepherd, young reporter for the United Press, walking briskly eastward through the Square.

Clearly visible to him was the New York University building filling half of the eastern side of the Square from Washington Place to Waverly Place. But he could not see, as he looked from his window, that Professor Frank Sommer, former sheriff of Essex County, New Jersey, was lecturing to a class of fifty on the tenth floor of the school building, or that directly beneath him on the ninth floor Professor H. G. Parsons was illustrating interesting points of gardening to a class of forty girls.

A block east of the Square and parallel to it, Greene Street cut a narrow path between tall loft buildings. Its sidewalks bustled with activity as shippers trundled the day’s last crates and boxes to the horse-drawn wagons lining the curbs.

At the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place, a wide thoroughfare bisecting the east side of the Square, the Asch building rose ten floors high. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company, largest of its kind, occupied the top three floors. As Dr. Winterbottom contemplated the peaceful park, 500 persons, most of them young girls, were busily turning thousands of yards of flimsy fabric into shirtwaists, a female bodice garment which the noted artist Charles Dana Gibson had made the sartorial symbol of American womanhood.

One block north, at the corner of Greene Street and Waverly Place, Mrs. Lena Goldman swept the sidewalk in front of her small restaurant. It was closing time. She knew the girls who worked in the Asch building well for many of them were her customers.

Dominick Cardiane, pushing a wheelbarrow, had stopped for a moment in front of the doors of the Asch building freight elevator in the middle of the Greene Street block. He heard a sound “like a big puff,” followed at once by the noise of crashing glass. A horse reared, whinnied wildly, and took off down Greene Street, the wagon behind it bouncing crazily on the cobblestones.

Reporter Shepherd, about to cross from the park into Washington Place, also heard the sound. He saw smoke issuing from an eighth-floor window of the Asch building and began to run.

Patrolman Meehan was talking with his superior, Lieutenant William Egan. A boy ran up to them and pointed to the Asch building. The patrolman put spurs to his horse.

Dr. Winterbottom saw people in the park running toward Washington Place. A few seconds later he dashed down the stoop carrying his black medical bag and cut across the Square toward Washington Place.

Patrolman Meehan caught up with Shepherd and passed him. For an instant there seemed to be no sound on the street except the urgent tattoo of his horse’s hoofbeats as Meehan galloped by. He pulled up in front of 23 Washington Place, in the middle of the block, and jumped from the saddle.

Many had heard the muffled explosion and looked up to see the puff of smoke coming out of an eighth-floor window. James Cooper, passing by, was one of them. He saw something that looked “like a bale of dark dress goods” come out of a window.

“Some one’s in there all right. He’s trying to save the best cloth,” a bystander said to him.

Another bundle came flying out of a window. Halfway down the wind caught it and the bundle opened.

It was not a bundle. It was the body of a girl.

Now the people seemed to draw together as they fell back from where the body had hit. Nearby horses struggled in their harnesses.

“The screams brought me running,” Mrs. Goldman recalled. “I could see them falling! I could see them falling!”

John H. Mooney broke out of the crowd forming on the sidewalk opposite the Asch building and ran to Fire Box 289 at the corner of Greene Street. He turned in the first alarm at 4:45

P.M.

Inside the Asch building lobby Patrolman Meehan saw that both passenger elevators were at the upper floors. He took the stairs two steps at a time.

Between the fifth and sixth floors he found his way blocked by the first terrified girls making the winding descent from the Triangle shop. In the narrow staircase he had to flatten himself against the wall to let the girls squeeze by.

Between the seventh and eighth floors he almost fell over a girl who had fainted. Behind her the blocked line had come to a stop, the screaming had increased. He raised her to her feet, held her for a moment against the wall, calming her, and started her once again down the stairs.

At the eighth floor, he remembers that the flames were within 8 feet of the stairwell. “I saw two girls at a window on the Washington Place side shouting for help and waving their hands hysterically. A machinist—his name was Brown—helped me get the girls away from the window. We sent them down the stairs.”

The heat was unbearable. “It backed us to the staircase,” Meehan says.

Together with the machinist, he retreated down the spiral staircase. At the sixth floor, the policeman heard frantic pounding on the other side of the door facing the landing. He tried to open the door but found it was locked. He was certain now that the fire was also in progress on this floor.

“I braced myself with my back against the door and my feet on the nearest step of the stairs. I pushed with all my strength. When the door finally burst inward, I saw there was no smoke, no fire. But the place was full of frightened women. They were screaming and clawing. Some were at the windows threatening to jump.”

These were Triangle employees who had fled down the rear fire escape. At the sixth floor, one of them had pried the shutters open, smashed the window and climbed back into the building. Others followed. Inside, they found themselves trapped behind a locked door and panicked.

As he stumbled back into the street, Meehan saw that the first fire engines and police patrol wagons were arriving. Dr. Winterbottom, in the meantime, had reached Washington Place. For a moment he remained immobilized by the horror. Then he rushed into a store, found a telephone, and shouted at the operator, “For God’s sake, send ambulances!”

The first policemen on the scene were from the nearby Mercer Street Station House of the 8th Precinct. Among them were some who had used their clubs against the Triangle girls a year earlier during the shirtwaist makers’ strike.

First to arrive was Captain Dominick Henry, a man inured to suffering by years of police work in a tough, two-fisted era. But he stopped short at his first view of the Asch building. “I saw a scene I hope I never see again. Dozens of girls were hanging from the ledges. Others, their dresses on fire, were leaping from the windows.”

From distant streets came piercing screams of fire whistles, the nervous clang of fire bells. Suddenly, they were sounding from all directions.

In the street, men cupped their hands to their mouths, shouting, “Don’t jump! Here they come!” Then they waved their arms frantically.

Patrolman Meehan also shouted. He saw a couple standing in the frame of a ninth-floor window. They moved out onto the narrow ledge. “I could see the fire right behind them. I hollered, ‘Go over!’”

But nine floors above the street the margin of choice was as narrow as the window ledge. The flames reached out and touched the woman’s long tresses. The two plunged together.

In the street, watchers recovering from their first shock had sprung into action. Two young men came charging down Greene Street in a wagon, whipping their horses onto the sidewalk and shouting all the time, “Don’t jump!” They leaped from the wagon seat, tore the blankets from their two horses, and shouted for others to help grip them. Other teamsters also stripped blankets, grabbed tarpaulins to improvise nets.

But the bodies hit with an impact that tore the blankets from their hands. Bodies and blankets went smashing through the glass deadlights set into the sidewalk over the cellar vault of the Asch building.

Daniel Charnin, a youngster driving a Wanamaker wagon, jumped down and ran to help the men holding the blankets. “They hollered at me and kicked me. They shouted, ‘Get out of here, kid! You want to get killed?’”

One of the first ambulances to arrive was in the charge of Dr. D. E. Keefe of St. Vincent’s Hospital. It headed straight for the building. “One woman fell so close to the ambulance that I thought if we drove it up to the curb it would be possible for some persons to strike the top of the ambulance and so break their falls.”

The pump engine of Company 18, drawn by three sturdy horses, came dashing into Washington Place at about the same time. It was the first of thirty-five pieces of fire-fighting apparatus summoned to the scene. These included the Fire Department’s first motorized units, ultimately to replace the horses but in 1911 still experimental.

Another major innovation being made by the Fire Department was the creation of high-water-pressure areas. The Asch building was located in one of the first of these. In such an area a system of water-main cutoffs made it possible to build up pressure at selected hydrants. At Triangle, the Gansevoort Street pumping station raised the pressure to 200 pounds. The most modern means of fighting fires were available at the northwest corner of Washington Place and Greene Street.

A rookie fireman named Frank Rubino rode the Company 18 pump engine, and he remembers that “we came tearing down Washington Square East and made the turn into Washington Place. The first thing I saw was a man’s body come crashing down through the sidewalk shed of the school building. We kept going. We turned into Greene Street and began to stretch in our hoses. The bodies were hitting all around us.”

When the bodies didn’t go through the deadlights, they piled up on the sidewalk, some of them burning so that firemen had to turn their hoses on them. According to Company 18’s Captain Howard Ruch the hoses were soon buried by the bodies and “we had to lift them off before we could get to work.”

Captain Ruch ordered his men to spread the life nets. But no sooner was the first one opened than three bodies hit it at once. The men, their arms looped to the net, held fast.

“The force was so great it took the men off their feet,” Captain Ruch said. “Trying to hold the nets, the men turned somersaults and some of them were catapulted right onto the net. The men’s hands were bleeding, the nets were torn and some caught fire.”

Later, the Captain calculated that the force of each falling body when it struck the net was about 11,000 pounds.

“Life nets?” asked Battalion Chief Edward J. Worth. “What good were life nets? The little ones went through life nets, pavement, and all. I thought they would come down one at a time. I didn’t know they would come down with arms entwined—three and even four together.” There was one who seemed to have survived the jump. “I lifted her out and said, ‘Now go right across the street.’ She walked ten feet—and dropped. She died in one minute.”

The first hook and ladder—Company 20—came up Mercer Street so fast, says Rubino, “that it almost didn’t make the turn into Washington Place.”

The firemen were having trouble with their horses. They weren’t trained for the blood and the sound of the falling bodies. They kept rearing on their hind legs, their eyes rolling. Some men pulled the hitching pins and the horses broke loose, whinnying. Others grabbed the reins and led them away.

The crowd began to shout: “Raise the ladders!”

Company 20 had the tallest ladder in the Fire Department. It swung into position, and a team of men began to crank its lifting gears. A hush fell over the crowd.

The ladder continued to rise. One girl on the ninth floor ledge slowly waved a handkerchief as the ladder crept toward her.