The Triangle Fire (13 page)

Authors: William Greider,Leon Stein,Michael Hirsch

The police also had to cope with fashionable women who drove up to the police line in their cars and asked to be let through. When told they would have to take their place at the end of the line, “they turned up their noses and ordered their chauffeurs to drive off.”

A policeman at the gate, in midafternoon, counted one hundred persons a minute entering the morgue—six thousand every hour. Yet the crowd didn’t seem to diminish.

A squad of officers went down the line in an effort to weed out those who obviously had no business there. But suppose even one of these could identify one of the bodies? The result of the weeding was a recognition of the fact that many who had come out of the morgue had returned to the line for a second visit. But the police had the satisfaction, as the

World

put it, “of yanking out and putting to flight not less than forty known pickpockets come for the purpose of nipping jewelry from the seared throats and charred fingers, of thumbing stealthily burned clothing in the hope of finding a purse.”

At five o’clock, Deputy Police Commissioner Driscoll arrived. He studied the endless line and said to the officers around him: “Good God! Do these people imagine that this is the Eden Musee? This doesn’t go on another minute!”

He ordered his captains and lieutenants to remove anyone who could not immediately give the name and the description of the relation or friend he was seeking.

In ten minutes the crowd in Misery Lane had been reduced from thousands to several hundred. Even these were closely scrutinized by Nurse Mary Gray, an assistant to Dr. Healy of the Charities Department, who was stationed at the entrance to the pier to question all who sought admission.

She had a wonderful searching eye, said the

World

, and many found themselves stammering foolishly when she questioned them. She turned them back “with sweetness and light,” but cleared the way quickly for those “in whose eyes she could read genuine grief and suffering.”

A big lieutenant standing nearby smiled. “She’s worth twenty cops,” he said.

Inside the morgue the cataloguing of the dead continued.

Rosie Solomon of 84 Christie Street took her position in the line leading to the morgue early Sunday morning, but it was one o’clock in the afternoon before she entered. Once inside, she made the circuit of coffins, looking only at the hands of those who lay in them.

When she reached Box No. 34 she stopped, her gaze fixed on a ring she seemed to recognize. She asked the attendant if there was also a watch on the body. There was. He opened it and she looked inside, seeing her own picture.

Rosie Solomon sank in a faint to the floor. She had found her fiancé, Joseph Wilson, by means of the ring and the watch she had given him. They were to have been married in June.

For Serafino Maltese, a young typesetter, grief was triply compounded. First he identified the body of his sister Lucia, aged twenty. Then he found the body of his sister, Rosalie, aged fourteen. At that point he fainted. As soon as he was revived, he began his sad march again, this time to search for the body of his mother, Catherine, aged thirty-eight.

Box 74 held the body of a woman whose regular features, said the

Sun

, “were without scratch or stain.” When she had worked in the factory the day before she must have looked very much as she did now in the pine box. But no one among the thousands who went by recognized her.

Outside the pier, since early in the morning, a line of black hearses had waited. Even before dawn, a common sight became that of two men carrying a rude coffin to one of the hearses, followed by their group of wailing women.

All day long, the

Herald

reported, “the somber equipages rattled over the rickety pavement, followed by the awestricken glances of the spectators.” There was much bantering among the undertakers who “chaffed each other good naturedly. For one day, at least, there was business enough for all.”

Between midnight and seven o’clock Sunday evening, close to 200,000 had come to the area around the temporary morgue. More than half had walked among the coffins.

Beginning on Sunday, the city’s newspapers published all through the week the list of the unidentified dead.

At midnight, thirty-three identified bodies, including two brought from New York Hospital, and fifty-five still nameless were moved to the regular morgue, 100 feet south of the pier. The work was done by Superintendent Yorke’s corps of derelicts, who carried the coffins through the light rain that had started to fall. One box contained only a skull and some charred bones.

Shortly after midnight another group of men was called up from the lodging house. These entered the empty pier, carrying brooms and mops and pails with which they cleaned away the stains and prepared to fumigate and disinfect the Charities Department pier.

The fifty-five bodies were set up head to head in two rows in the center of the rotunda floor of the morgue. Around them, the dull gray walls were lined with the square doors of vaults reserved for the normal flow of the city’s unknown and violently dead.

Early in the morning, the police had some difficulty with the crowd near the exit of the morgue. A number of times hysterical women rushed toward a small group carrying out a coffin and threatened to seize it. The police believed these were relatives who had not yet found the one for whom they searched and were fearful that now that the number of bodies was diminishing, some one might claim theirs in error.

Though Monday was a workday, the crowd was only slightly smaller than the day before. Nurse Gray, backed by six burly policemen, held her post at the entrance to the morgue. Among those she stared down through her pince-nez glasses were some young men who claimed to be medical students but could not prove it.

At one time during the day word spread through the waiting crowd that immediate admission could be gained by asking for “the girl in the blue skirt.” The

Sun

said about five hundred did ask but were told “there were no blue skirts around any of the dead.”

But in the course of the long afternoon, many did find their own. Ignatzia Bellotta’s father came in from Hoboken to look for the body of his sixteen-year-old daughter. When he found her, he knew her by the heel of her shoe. The

Times

reported, “He had taken her shoe to be repaired and the shoemaker had put in a plate whose peculiar construction he recognized.”

Five times that day, two men came to look at the body in coffin 138. They were certain she was Mrs. Julia Rosen of 78 Clinton Street. Commissioner Driscoll, remembering the $852 found in Mrs. Rosen’s stocking, insisted that a close relative of the victim be produced before any claims would be met.

They produced her. At 4:30 in the afternoon, the two men returned, leading fifteen-year-old Esther Rosen, the woman’s daughter. She leaned over the box and touched the head of the dead woman. “It’s mamma’s hair. I braided it for her. I know—I know.”

Esther and two younger brothers had waited at home all day Saturday and Sunday for their mother and brother, both of whom worked at Triangle. Then the police knocked on the door. Esther didn’t know the meaning of the word “bank” but explained that the family had come to America four years ago, the father had died, and the mother always feared to leave the family’s savings at home.

One mystery had been solved; another remained.

Who was the beautiful woman in the coffin numbered 74? Her hair and her face were undamaged. When leaping to death she had apparently folded her arms. Officials were baffled by the inability of any of the Triangle survivors to recognize her. Then Mrs. L. Bongartz, a matron on the municipal ferryboat running between the Charities pier and Randall’s Island, said she recognized the woman as a mother who often made the trip to visit her child in the hospital. Miss May Dunphy, superintendent of nurses on the Island, was directed by Deputy Commissioner Goodwin to come to the morgue with any other nurses who might help in the effort to identify the woman.

Dominick Leone, tiptoeing hat in hand around the bodies, had found his two cousins, Nicolina Nicolose and Antonina Colletti, while they were still on the Charities pier. He came to the morgue Monday evening with other members of the family to look for his niece.

A hailstorm broke with sudden ferocity as they entered the rotunda. The glass panes forming the ceiling had been opened. The arc light hanging from the center of the dome began to swing wildly in the wind and the rain and hail fell on the faces of the dead.

Attendants ran to close the roof panes. Leone and his relatives ignored the entire disturbance, quietly moving from box to box until one of the group hesitated. Where they stopped, Dominick leaned over the box, brushed aside the long hair partly covering the face. One of the women in the group cried out. The search had been successful.

Not all of Triangle’s dead were in the morgue.

Two who had leaped for their lives lay in the New York Hospital fighting to live.

Daisy Lopez Fitze of 11 Charlton Street didn’t have to work. Her husband had recently returned to Switzerland with their small savings to buy an inn. He had left his wife enough to live on until he would send for her. But Daisy was determined to save every penny so she went to work at Triangle.

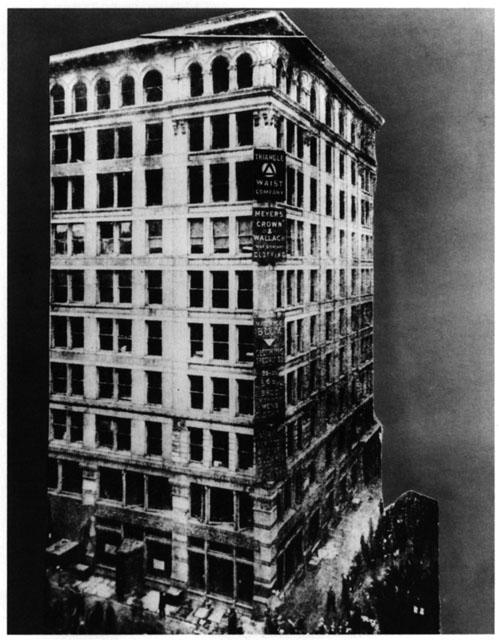

1. The Asch building housing the Triangle Shirtwaist Company on the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors.

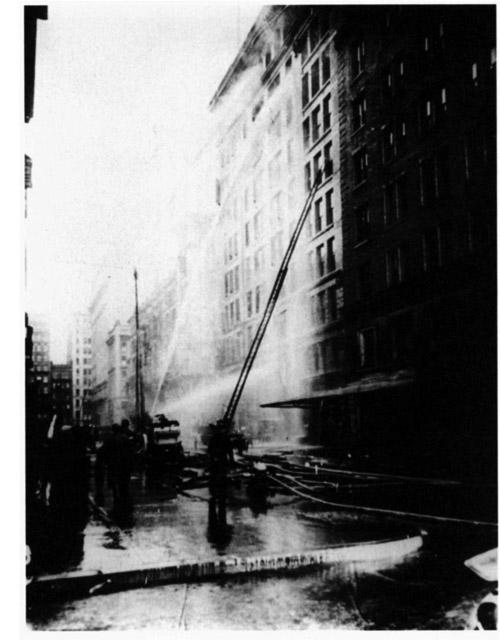

2. Tons of water were poured into the Asch building long after the fire was brought under control.

3. After the fire was brought under control, bodies were laid out and tagged on the sidewalk across the street from the Asch building.

4. Three officers carrying personal effects of those killed in the fire.