The Trial Of The Man Who Said He Was God (4 page)

Read The Trial Of The Man Who Said He Was God Online

Authors: Douglas Harding

Tags: #Douglas Harding, #Headless Way, #Shollond Trust, #Science-3, #Science-1, #enlightenment

THE HUMANIST

COUNSEL: The court would like to hear about your relationship with the Accused, in so far as it bears on the crime he stands accused of.

WITNESS: I’m a University Lecturer in Philosophy, and my special interest is the history of humanism. Some twenty years ago John a-Nokes attended a course of lectures I was giving on the ideas behind the French Revolution. I knew him vaguely as some kind of mystical freethinker, with a lively mind much given to enthusiasms. An oddball, you could say, if not a screwball. Since then we’ve bumped - and I mean bumped - into each other occasionally. From early days it was clear that we had little in common. Whenever our paths crossed, we crossed swords. This only resulted in our positions hardening and drifting even further apart. Gradually it dawned on me that he wasn’t just ordinary religious, or Bible-thumping prayer-meeting religious, but what I can only call God-awful religious. I read as much of his stuff as I could take, which was very little. I listened to rather more than I could take on the subject of Who He Really Is. I concluded that we don’t live in the same universe. We’re mutually out of earshot. This deification syndrome, with its delusions of grandeur, leave me numb and practically speechless anyway.

COUNSEL: ‘Deification syndrome’, you say. Can you enlarge on that?

WITNESS: He’s got so far above himself that he’s out of my reach. If I could get to the man, I would challenge him to produce anyone who seriously regards him as divine. Why can’t he see that his true dignity is to accept the world’s view of him as only human after all? I’d like to see him stop posturing and, with Alexander Pope, admit his limitations:

Know then thyself, presume not God to scan,

The proper study of mankind is man.

Defence:

The Divinist

MYSELF, to the Witness: This is ridiculous! It just isn’t true that everyone says I’m essentially human. You must know about the Perennial Philosophy, according to which you and I are essentially divine - like it or lump it.

WITNESS: Well, there are all sorts of fantastic philosophical systems. I’ve forgotten (if ever I knew) most of what the so-called Perennial Philosophy teaches. Apparently it wasn’t worth remembering.

MYSELF: Then let me remind you. It’s to be found, more or less concealed, at the heart of all the great spiritual traditions. It insists that, really and truly, I am the One Self - alias Atman-Brahman, the Buddha Nature, Tao, Spirit, Being, God, the Aware No-thing that embraces All things. And that the whole reason for living is to realize that at core I am This and This Alone.

In that case my true dignity consists in my

denial

that I’m only human after all. A dignity arising out of lies isn’t anything of the sort. It’s disgraceful and shaming and due for a tumble.

You appeal to popular opinion, that many-headed monster. Since when has philosophy subscribed to the dictum

Vox populi, vox Dei?

Rather it says

Vox populi, pox Dei!

Your common sense is nonsense, till the Perennial Philosophy brings you to your senses.

WITNESS: Why has this

soi-disant

Perennial Philosophy won for itself virtually no place in the history of philosophy? Because it makes horrible jokes? There must be a good reason why it doesn’t figure in serious textbooks. I, who teach philosophy, know as much about it as I know about astrology. I suggest it’s obscure because it deserves to be obscure.

MYSELF: In the East it has obscured all other philosophies for twenty-five centuries. Here in the West, it’s the

only

philosophy that has survived intact down the ages, and is now more vigorous than ever. It doesn’t date. Many a passage from the

Tao Te Ching

of 300 BCE reads as freshly today, and rings as true, as on the bright morning of its composition. No other body of doctrine is so free of historical and geographical discoloration, so practical no matter what the cultural constraints, so simple and self-evident and yet so deep. No other has stood half so well the test of time and of day-to-day experience. And yet no other is so wild, so daring, so madly and gloriously

happy!

WITNESS: I wonder -

COUNSEL: Your Honour, what’s going on in this lawcourt? Is a Witness being cross-examined? Or are two old sparring partners enjoying a knockabout at the Crown’s expense?

JUDGE: It’s all most irregular. But I think the outcome of the bout may have a bearing on the case, and that’s what matters… The Accused may proceed, provided he’s not much longer coming to the point.

MYSELF: I’ve arrived, Your Honour. I don’t know about the Witness...

WITNESS: The trouble with dogmatic and speculative systems like this is that there’s no way of testing them. Give me the full address with area code of this blessed deity of yours, tell me what time he’s at home, and how to plant my foot in his door and how to recognize him when I get inside - and I’ll take you and him seriously. Make this information so precise that anyone anywhere can track him down and find exactly the same blessed what’s-it, and I’m your disciple - grovelling at your lotus-feet.

MYSELF: Done! I’ll hold you to that! So far from being speculative or vague, the Perennial Philosophy tells you precisely:

(1)

Where

to find God: namely, right where you are. Which is in the witness-box of Court One, the New Bailey, Holborn, London EC4 England, Great Britain, Europe...

(2)

When

to find God: namely, right now. Which is 11.37 Greenwich Mean Time.

(3)

How

to find God: namely, by turning the arrow of your attention round 180° and looking inwards - looking in at what you’re looking out of. And with childlike sincerity taking what you find there.

(4)

What to look for:

namely, that which has no form, features, colour or limits, but is like light or air or clear water or space. Great space, filled to capacity with what’s on show. Which is Judge and Jury and Accused and all the rest, with the sole exception of yourself. Great Space,

aware

of itself as thus empty and thus full.

The Perennial Philosophy has consistently and persistently put forward a hypothesis so amazing and so delectable - one’s essential Godhood, no less - that it cries out to be tested by every available means, just in case it should turn out to be true. For good measure, as we’ve seen, it comes up with just the right tools for the job.

Precisely the four tests you listed, as it happens.

Precisely - in terms of feet and inches, of hours and minutes and seconds, of degrees of the compass. And to blazes with all spiritual-metaphysical waffle and cotton wool!

Tennyson said that God’s nearer than my hands and my feet and my breathing, Muhammad that He’s nearer than my jugular vein. Well then, let me see if they knew what they were talking about. Following those four guidelines we are agreed on: (1) I point, with both forefingers, at this nearest of places, the place I’m looking out of; (2) I do so now; (3) I do so in the spirit of a little child who takes what he gets; and (4) I notice whether what I’m pointing at is face-like or space-like, human or non-human, a thing or no-thing, small and bounded or limitless, dead to itself or alive - alive to Itself, in all Its blazing obviousness and uniqueness and - yes! - power. It looks as if Eckhart got it right: ‘When the soul enters into her Ground, into the innermost regions of her Being, divine power suddenly pours into her.’

COUNSEL: First, members of the Jury, we were regaled with the spectacle of a fairly friendly punch-up. Now we have the winner positively exploding with admiration at himself - at the divine power he wields. But of course! He worships the ground he walks on- all the way to the dock today for sure. All the way to the scaffold tomorrow, it may be.

MYSELF: I appeal to His Honour and to each member of the Jury to ignore Counsel’s blatant attempt to whip up prejudice against me and to

test

with an open mind what I’m saying. Just to watch and listen to me carrying out this crucial experiment would be worse than useless. What have you and I to fear from the truth? I beg you to follow my example, point right now - repeat,

right now

- to the Spot that’s nearer than

your

breathing, and see

for yourself

what I’m going on about. Don’t be nervous! Even if your mother (like mine) told you it was rude to point at anyone, I tell you it’s all right to point at this One. He loves it! O how He loves it!

What is it like right where

you

are? What, on present evidence, are

you

looking out of? Who lives at the Centre of

your

universe? Only

you

are in a position to see and to say.

Till you have addressed - let alone settled - the question of your own identity, how can you settle mine? Wouldn’t it be absurd and unjust to condemn me for claiming to be Someone, without looking to see whether

you

are that very same Someone? That incredible Someone?

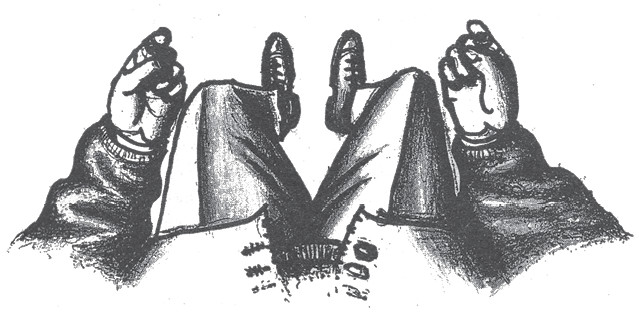

I ask you: looking

in

now at what your two forefingers are pointing at, isn’t it Aware Capacity for them and for the scene that lies between - namely, those little feet and those foreshortened legs, and those thighs, and the lower part of your trunk? Doesn’t Diagram No. 3 (which I ask you to turn to) give a fair representation of what you’re experiencing?

Diagram No. 3

Just what name do you propose to give to this Immensity that’s nearer to you than your hands and your feet and your breathing, to the Radiance here that is the Light and all It lights up? To call It Mary Smith or William Brown or Gerald Wilberforce or John a-Nokes would be as perverse as to call it Little Green Apples. It’s precisely the opposite and the absence of those persons. Here is the one place in my world that’s clean of John a-Nokes, where I’m let off being that little fellow, so opaque and unluminous. Here, at my Centre, is the one place where there shines the Light that lights up the light. This is the Light which, according to Dante, ‘makes visible the Creator Himself to His creature, who finds his peace in seeing Him’.

To put Jack here at the Centre of his world isn’t just diabolical pride and blasphemy: it’s being horrible to myself. It’s playing Bottom the Weaver, and mounting a jackass’s head on these shoulders. It’s unbelievably stupid. The third person’s not for divinizing, the First Person’s not for humanizing. True humanism

there

is true divinism

here.

The very best I can do for Jack is to keep seeing him off, and God in.

In so far as I am, I am Him. As Rumi explains:

‘I am God’ is an expression of great humility. The man who says ‘I am the slave of God’ affirms two existences, his own and God’s, but he that says ‘I am God’ has made himself non-existent and has given himself up... He says ‘I am naught, He is all: there is no being but God’s.’ This is extreme humility and abasement.

Out of the scores of further witnesses I have lined up, these are the ones I have chosen:

In appearance a man, in reality God.

Chuang-tzu

Jesus said: What I now seem to be, that am I not... And so speak I, separating off the manhood.

Acts of John

They saw the body, and supposed he was a man.

Rumi

Man is not, he becomes: he is neither limited being nor unlimited, but the passage of limited being into unlimited; a search for his own perfection, which lies beyond him and is not himself but God... The stirring of religion is the feeling that my only true self is God.

A. C Bradley

No matter how often he thinks of God or goes to church, or how much he believes in religious ideas, if he, the whole man, is deaf to the question of existence, if he does not have an answer to it, he is marking time, and he lives and dies like one of the million things he produces. He thinks of God, instead of experiencing being God.