The Transformation of the World (38 page)

Read The Transformation of the World Online

Authors: Jrgen Osterhammel Patrick Camiller

A novelty of the nineteenth century was large-scale migration beyond and after the slave trade. It gradually developed after 1820 and dramatically increased after the middle of the century, at a rate significantly faster than that of the world population. Migration studies has long ceased to see it as an undifferentiated flow of “masses.” The picture is now more of a mosaic, made up of local situations in which the village community and its partial transplantation are often the focus of a microstudy. Up to a point the components of such migration histories were the same across different cultures: there were pioneers, organizers, and group solidarity. The decision to migrate was more often collectively made by the family than by isolated individuals. The transportation revolution improved the logistical possibilities, while the more extensive organization and faster speeds of capitalism required a more mobile labor force. Most emigrants, whether from Europe, India, or China, came from the lower classes; they aspired to join the middle classes in the host country, and they achieved this more often than former slaves or their descendants.

188

The link between internal and external (“transnational”) mobility was variable. It would be superficial to claim that life in the modern world is always and everywhere faster or more mobile than in the past. Indeed, studies on Sweden and Germany long ago showed that horizontal mobility within societies, and not only the intensity of emigration, tended to diminish in the twentieth century, at least in times of peace.

189

In the case of Europe, the high level of mobility in the late nineteenth century was exceptional.

Up to the 1880s, governments usually put little in the way of cross-border migration, although in individual cases migrants might be subject to supervision and harassment. This administrative restraint was an important prerequisite for the emergence of the vast systems of migration. The age of state-sponsored emigration began only after the turn of the centuryânot least with an eye to the beneficial effects of remittances sent by the emigrants to their kinsfolk back home.

190

The Japanese government embarked on active encouragement (and even funding) of emigration to Latin America. The Australasian colonies also pursued an active immigration policy, which in their case was especially necessary on account of the high costs of “unassisted passages.” Australia needed people badly and had to compete with North America for them. Mass emigration there was possible only because the government began to offer financial inducements after 1831. Nearly half of the 1.5 million Britons who moved to Australia in the nineteenth century received official payments to cover their costsânot loans but grants, which came overwhelmingly out of the public purse. For decades the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission in London was one of the most important and successful branches of the Australian state. This also facilitated the tasks of control and selection. In the conflict between the British government, which wanted to offload its “plebs,” and colonies interested in a “higher class” of settler, the receiving countries prevailed in the end. The Australian case confirms

the economic rule that governments of democratic states prefer an immigration policy that can be expected to maintain or increase the income of their electorate. The next question is when immigrants are to be offered naturalization on equal terms with the rest of the population.

The motives of individual migrants were, of course, culturally shaped. People from very hot regions do not like to work in very cold countries, and vice versa, and the tendency is to go where others from one's own homeland or members of one's own social group already have a reasonably contented life and can provide crucial advice and information. At the extremeâfor example, among the Irish after the Great Famineâa magnet effect was set up that made emigration seem the only sensible thing to do. When people who left Scotland to supply an astonishing share of the workforce needed for conquering and running the British Empire responded to meager chances at home, they did this at various levels. Some were destitute peasants or younger sons of noble families, others alumni of Scotland's excellent universities, which produced more lawyers or medical doctors than the domestic labor market could absorb.

191

In other respects, however, where the scope for decision was fairly wide, attitudes might follow a culturally neutral rationality. One central element was the differential in real wages between the Old and the New World. The gap narrowed over time as a result of emigration, and this was a major reason why emigration itself slowly diminished.

192

But the wage motive was present everywhere in the world. In the last third of the nineteenth century, Indian workers migrated more to Burma than to the Straits Settlement, since wage levels were significantly higher there until the beginning of the Malayan rubber boom. Many other considerations pointed ahead to the future. Small agricultural producers frequently accepted temporary proletarianization in order to be spared permanent misery. Prognoses as to the outcome of emigration were always uncertain. The ill-informed or credulous allowed themselves to be lured into risky adventures by tales of fabulous wealth or by false promises of marriage. The topic becomes exciting for historians when it is a question of explaining micro-differences, for example, why one region produced more emigrants than others. Large interlinked systems must be granted a certain life of their own, although they form, persist, and change only through the interaction of countless personal decisions in particular life situationsâin short, through human practice.

CHAPTER V

Â

Living Standards

Risk and Security in Material Life

1 Standard of Living and Quality of Life

Quality and Standard of Material Life

A history of the nineteenth century cannot omit the material level of human existence, and we shall bring together the little that research can tell us about this at a

general

level. First, a distinction needs to be drawn between “standard of living” and “quality of life”: the former is a category from social history, the latter from historical anthropology.

1

Quality of life includes the subjective impression of well-beingâindeed, of happiness. Happiness is bound up with individuals or small groups; its quality cannot be measured and is difficult to compare. Even today it is nearly impossible to decide whether people in society A are more content with their lives than people in society B. As for the past, it is scarcely ever possible to reconstruct such appreciations. Furthermore, we need to differentiate between poverty and misery. Many societies in the past were poor in market goods yet enabled people to live a happy life; they based themselves not only on the market but also on community economics and the economics of nature. Personal or collective unhappiness affected not so much those without property as those who lacked

access

âto a community, to reliable protection, to land or forest.

“Standard of living” is a touch more palpable than “quality of life.” But it involves a tension between the “hard” economic magnitude of income and the “soft” criterion of the utility that an individual or group derives from its income.

2

Recently it has been suggested that “standard of living” should be defined in terms of the capacity to master short sharp crises, such as a sudden drop in income due to unemployment, higher prices, or the death of a family breadwinner. Those who manage to pull through such crises and to plan their lives long into the future may be said to have a high standard of living. More specifically, under premodern conditions this was mainly a question of the strategies that individuals and groups applied to avoid an early death, and of their degree of success in doing so.

3

Economists are rather more robust than social historians in their approach to the history of living standards. They attempt to measure the income of distinct economies (which in the late modern age are mostly national economies) and divide them according to their population level. In this way we obtain the famous per capita GDP (gross domestic product). A second question that economic historians like to ask concerns the ability of economies to save, hence to preserve values for the future, and perhaps also to invest part of what is saved so that it creates values in turn. However, there is no univocal positive correlation between statistical economic growth and the actually experienced standard of living. Growth of any degree, even high, does not necessarily translate into a better life. For a number of European countries, it has been shown that real wages moved downward in the early modern age, yet the material wealth of their societies increased overall; a massive long-term polarization must have occurred, whereby the rich grew richer and the poor poorer.

4

So, there is by no means a direct correlation between income and other aspects of an improved quality of life. When Japanese incomes gradually rose in the nineteenth century, growing numbers of consumers could afford the more expensive (and prestigious) polished white rice. But this created a problem since the vitamins present in rice husks were now lacking. Even members of the emperor's family died of beriberi, the vitamin B1 deficiency disease that is a risk associated with prosperity. The same link is observable between sugar consumption and poor dental health. History does not provide enough evidence that economic prosperity automatically translates into a higher biological quality of life.

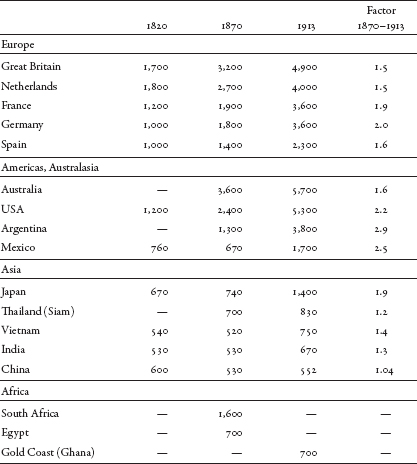

The Geography of Income

However uncertain the income levels in the age before global economic statistics, the most plausible quantifications must serve as the basis for discussion (see

table 5

, which draws on Angus Maddison's work).

For want of statistical data, Maddison's estimates can be used only with considerable qualification. In particular it has been objected that they set Asia's economic performance too low. They are inherently “impossible,” even if Maddison has attempted, by also making broad use of qualitative sources, to create an approximate impression that roughly reflects the true proportions. Nevertheless, if we take his figures as an at least plausible account of the relations of magnitude and accept that the GDP estimates have some degree of validity, then the following points stand out:

âª

Between 1820 and 1913, the richest and poorest regions in the world moved wide apart in their material living standards. The difference was 3:1 or perhaps 4:1 in 1820 but had climbed to at least 8:1 by 1913.

5

Even if such figures are not trusted, it is indisputable that the prosperity and income gap in the world increased considerably during this period, probably more than in any other epoch, though in the context of an overall rise in global wealth. Only after 1950 did this trend subside, and even then there was a stable group of “ultra-poor” countries that benefited from neither industrialization nor the export of raw materials.

6

Table 5: Estimated per Capita Gross Domestic Product in Selected Countries, 1820 to 1913 (in 1990 $)

Source:

Maddison:

World Economy

, pp. 185, 195, 215, 224 (rounded up or down; factor calculated).

âª

Alongside the industrial heartlands of northern and western Europe, the countries that Maddison calls “Western offshoots” (the neo-European settler societies of North America, Australasia, and the River Plate) achieved the highest income growth.

âª

The United States and Australia overtook the European frontrunners

before

the First World War, but the differences within the group of “developed”

âª

Â

countries were much smaller than those that divided them from the rest of the world.

7

âª

The formation of a statistical “third world,” consisting of countries that made little progress from their low starting point, was already a feature of the nineteenth century, especially its last few decades.

âª

There was one exception in Asia and one in Africa: Japan began to industrialize in the 1880s, and around the same time South Africa discovered the largest gold deposits in the world.

âª

In many countries it is possible to identify an approximate turning point, when average prosperity, and therefore consumption potential, began to increase markedly. This point came in the second quarter of the nineteenth century for Britain and France, around midcentury for Germany and Sweden, in the 1880s for Japan, after 1900 for Brazil, and sometime after 1950 for India, China, and (South) Korea.

8

2 Life Expectancy and “

Homo hygienicus

”

The limited value of Maddison's income estimates for the question of living standards becomes apparent when we look through his chapter on life expectancy. Here the “poverty” of Asia in comparison with Europe is not clearly reflected in the average length of human life, which is in turn a fairly reliable indicator of health. The lives of Japanese, the healthiest people in Asia, were scarcely shorter than those of Western Europeans, despite their lower per capita income. In fact, most people had the same life span everywhere in the early modern age. Before 1800 only small elites such as the English nobility or the Genevan bourgeoisie attained a male life expectancy above forty years. In Asia the figure was somewhat lower, but not dramatically so. In the case of the Manchurian Qing nobility, life expectancy hovered around thirty-seven years for those born in 1800 or thereabouts and thirty-two years for the generation born around 1830âa deterioration that mirrored the general trend of Chinese society.

9

As to Western Europe, life expectancy at birth averaged thirty-six years in 1820, with a peak in Sweden and a trough in Spain, while the corresponding figure for Japan was thirty-four years. By 1900 it had risen to forty-six to forty-eight years in Western Europe and the United States; Japan was almost level at forty-four years, with the rest of Asia behind it.

10

Considering that Japan's economy was then at least a generation behind those of the United States and the advanced European countries, we can see that, under conditions of

early

industrialization, it managed to achieve health standards that were elsewhere characteristic of

high

industrialization. However much weight one attaches to income estimates, the fact is that the notional average Japanese in 1800 led a more frugal existence than a “typical” Western European, without having a significantly shorter life expectancy. A hundred years later, after societies in both parts of the world had multiplied their

wealth, the differential had not noticeably shrunk. Probably, though, national wealth was more evenly distributed in Japan, and the Japaneseâwho

today

have the highest life expectancy in the worldâwere unusually healthy. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, they had diets, house-building techniques, dress habits, and public and private hygienic customs that reduced their susceptibility to disease, and they were exceptionally resource effective.

11

The Japanese were “poorer” than Western Europeans, but it cannot be said that their lives were therefore “worse.”