The Transatlantic Conspiracy (9 page)

“You will?” Erich said, sounding surprised. He quickly recovered his easy smile. “You will. Well, that's wonderful. Good. That is to say, it's good.”

“We'll speak to the head steward to make the arrangements,” Jacob added.

“Lovely. What time do we eat?” Rosalind asked.

“Four o'clock,” Alix answered. “So that we all have plenty of time to change for the ball afterward.”

Rosalind blinked. “Change for the ball? We're already dressing for dinner. How many times are we changing today?”

“Twice by the schedule,” Cecily said. “But I'm hoping for more. I've brought so many dresses, I don't know if I shall have occasion to wear them all.”

Chapter Nine

R

osalind thought about not changing for dinner and saving the effort for the ball. Mother would be horrified at the notion, which made it all the more appealing. But then she remembered her father's letter: “The public will judge you.” Meaning “the public will judge the family.” If Rosalind flouted convention too much, too openly here on the train, her parents would be furious. They might never let her out of Pittsburgh again, at least not until she was married.

So Rosalind changed into something simple and understated: a pale-green evening dress that demanded as little effort as possible. Better to be comfortable than fashionable, she reasoned. But once she and Cecily and Alix were seated with Jacob and Erich over carrot soup, fillet of salmon, and game fowl, she began to regret her decision.

Both Cecily and Alix had taken pains to make themselves pretty for the boys, and worse, both boys had done the same. Jacob was in uniform, of course, just as he had been the night before. Erich wore a white tie and dress coat, as did most of the other men. Everyone at the tableâindeed, everyone in First Classâhad put tremendous effort into looking their best. All of which had the unfortunate effect of making Rosalind appear even more like an outsider. Or worse still, like an actual chaperone.

By the time dessert sorbets and after-dinner chocolates were served, Rosalind had drifted completely out of the flirty, mindless conversation. The four laughed over a faux pas that some viscount had committed during a recent wedding ceremony between two aristocrats Rosalind had never heard of. She didn't recognize a single name. She couldn't follow, nor did she care to.

The lone American is indeed alone

, she thought.

Rosalind tried to soothe herself with the music of the orchestra. Wagner, of course, to complement the eagles, lest anyone forget the station had been built by the Germans. Her thoughts turned to Charles. He would have included her in the conversation, if only out of politeness. He always did. He should have been here. What had really happened to him? It made no sense.

She glanced at the train, parked alongside them. Only First Class passengers could dine in the station concourse; only they could be serenaded by the orchestra. Second Class had been allowed out earlier, to stretch their legs. Rather like cattle. For the meal they were confined to their own dining cars. The ball wasn't on their itinerary, either.

Rosalind sighed. She would have expected better of Father. He'd organized all of this, knowing his own family would have traveled Second Class if he hadn't proved himself a capable industrialist. Their Scottish cousins wouldn't be able to afford any ticket whatsoever; they would be porters or waitstaff if aboard at all. But perhaps the decision to adhere so firmly to class distinctions hadn't been Father's to make. He had Old Money partners with Old World priorities. He was obliged to follow their rules, and to pretend to respect their prejudices, for the sake of business. It was no small part of his success.

Oh, dash it all

, she thought. If her foul mood got the better of her, this was going to be a very long journey, indeed.

â¢â¢â¢

The hour for the

ball was approaching and Doris still hadn't arrived. Rosalind had spent the better part of two hours alone in her room, expecting Doris to come by at some point to “assist” her after she'd finished with Cecily. Not that Rosalind minded being left to dress on her own, of course. But Cecily could have made clearer that she would take longer than usual. Then again, Rosalind should have known that intuitively, given her friend's flirtations with Jacob. Alix certainly would have. But Alix had her own servant.

Left to her own devices, Rosalind chose her pink gown, the one with the embroidered roses and the mother-of-pearl beading. Cecily would appreciate it. She always called it Rosalind's “rose dress”; “a rose for Rose,” as she put it. Rosalind had worn it many times in London, and each time Cecily had pointed out how perfect the color was for her.

When the clock finally struck seven, Rosalind left her room. If she waited any longer, she reasoned, she might end up sitting there all night in her ball gown.

â¢â¢â¢

In the grand concourse,

the tables and chairs had already been cleared, and wooden paneling had been laid atop the eagle mosaic to provide a suitable dance floor. Rosalind wished some of the other eagles could have been covered as well. A ball was no place for national pride. A ball was tailor-made for fun lovers like Cecily, as it should be. Rosalind looked this way and that for her friend among the swelling crowd of First Class passengers.

The orchestra began to tune their instruments. The dancing would start very soon

. . .

Rosalind froze in place. She felt a curious sensation on the back of her neck. As if she was being watched, just as she'd felt in the library. Sure enough, she spotted the mustached man in the brown suit. He was staring right at her. When their eyes met, he shoved his way back through the crowd and into a Second Class car of the train, vanishing.

She took a few breaths to steady herself.

“Rose?” a voice cried.

Rosalind blinked rapidly several times and summoned the bravest smile she could. Alix, Erich, and Jacob swept toward her through the crowd. Erich in particular looked rather smart in his white tie and black suit. But she didn't even notice what the others were wearing until they reached her; she was too shaken.

“Hello, Alix,” Rosalind said, holding her at arm's length. “You look lovely. Blue suits you, it really does.”

Alix blushed and said, “Oh, well, thank you

. . .

”

Erich and Jacob both bowed to her in unison. Then Erich took a step forward and took her hand gently, bowing over it while he smiled at her.

“Fräulein Wallace,” he said, letting her hand linger in his for a rather pleasant moment. “You look

wunderbar

, if you will permit my saying so. Truly

. . .

a rose, like your namesake.”

Rosalind did her best to look poised and elegant, even as she felt her cheeks warming at the compliment. “Very kind of you to say, Herr Steiner.”

“I am surprised at how cool it is here,” Alix announced, gazing off toward the crowd. “I mean, with all the people. It's lovely, not at all stuffy like I thought it would be.”

“It's all done with salt water,” Rosalind said. She thought to explain further, but she found that Erich was still gazing at her, in a manner that she found both engaging and most uncomfortable. It made her tongue-tied. After a few moments, she forced herself back to her senses. “Have any of you seen Cecily? I'd have thought she would be here by now.”

Jacob exchanged looks with Alix. Erich gave a slight shrug and looked back toward the train.

“I thought she was with you,” Alix said. “I knocked on her door but she was not there.”

Rosalind frowned and studied the crowd again.

“Perhaps she's fallen asleep,” Erich ventured.

“Cecily? Asleep?” Rosalind shook her head. “You'd be hard-pressed to find her tired after a ball, and certainly not before one.”

“Could she still be dressing?” Alix asked, though she sounded very skeptical. “She may not have heard me when I knocked, I suppose.”

“Seems unlikely,” Rosalind said. “I know the walls are soundproof, but she should still be able to hear a knock on the door.”

Erich smiled and said, “Well, I wouldn't worry too much about it. I am certain she will arrive eventually. Uh

. . .

in the meantime

. . .

” He extended his hand toward Rosalind. “Could I perhaps have the next dance?”

Rosalind paused. He was smiling at her. The orchestra had just begun playing a waltz, “The Blue Danube.” The music, the splendor of the ambiance, the rose-colored dress, the ball beneath the sea, this handsome boy asking for a dance

. . .

It all seemed like something from a fairy tale.

And suddenly she thought of Charles.

Rosalind hesitated and drew her hand back. Why had she thought about Charles? Aside from the fact that he'd abandoned her on this train? Yes, he was handsome. Yes, she was fond of him. And then thinking about Charles made her think about Cecily.

“No,” she said.

Erich blinked in surprise.

“Not just yet,” Rosalind quickly clarified. “I am so sorry, Erich, but I simply cannot enjoy the dance without knowing what has become of Cecily.”

“Ah, of course,” Erich said. He put on a smile. “Go, see to your friend. But do hurry back, yes?”

“I will, thank you,” Rosalind said. As she turned to go, Alix took her arm and began walking with her.

“I am going with you,” she whispered.

“But wouldn't you rather stay?” Jacob called after her.

Rosalind glanced back over her shoulder. “Steady on, gentlemen,” she said. “The night is young, and we surely cannot monopolize you the whole time, now can we? Now do get us some punch for when we return.”

â¢â¢â¢

After the first few

knocks, there was still no answer from Cecily. Rosalind tried again several times, each louder than the last.

“Cecily?” she shouted. “Are you in there?”

Beside her, Alix pressed her ear up against the door. “I don't hear anything,” she said. “Could she be elsewhere?”

“I suppose she may have gone to one of the other compartments, but why? And for that matter, where? The dining cars? We've already eaten. One of the parlors? Everyone is out in the station. The library?”

Alix smiled. “Yes, quite likely,” she joked.

On a whim, Rosalind tried the door handle, though she knew that it would be locked. Only it wasn't. Frowning, Rosalind slid the door open and stepped inside, with Alix following closely behind her.

Then she stopped.

Cecily was there. On the floor. Not moving. Not breathing. Eyes open and vacant. Her body was sprawled next to Doris's body, which lay a few paces away. Both were covered in bloodâblood that had soaked the carpet and splattered against the walls and furnishings. Cecily was still in a state of undress. Her ball gown lay on the bed, waiting to be put on. Her jewelry was arrayed on a side table, waiting to adorn her. It seemed Doris had been doing Cecily's hair when

. . .

whatever it was had happened.

Rosalind felt cold. She took a few uncertain steps toward the bodies. Alix held her back, clinging to her arm. Cecily's throat had been cut, and the cut had not been clean. Doris had been dispatched in much the same way.

Alix started to tremble, her hands clenching spasmodically into fists. She slowly looked up at Rosalind.

“Mein Gott!”

she cried. “Cecily!”

And with that, she fainted dead away and fell into Rosalind's arms.

Chapter Ten

A

fter that, everything became a blur.

A porter arrived, summoned by Alix's cry. The poor man retched from the sight and staggered back into the corridor. His scream of horror brought more men, of whom enough managed to keep their heads to usher Rosalind and Alix out of the room.

And then, quite suddenly it seemed, Rosalind was sitting on a sofa in one of the blue-and-gold parlors, comforting Alix.

The girl was sobbing into her shoulder. By God, Rosalind wanted to cry as well. But she found that she could not. She found herself unable to do anything but sit perfectly still, staring straight ahead while she stroked Alix's hair and murmured, “It's okay. It's okay. It's okay

. . .

”

She didn't even know what she was saying. All she could see were Cecily's dead eyes, staring at nothing, in a pool of blood

. . .

The door opened.

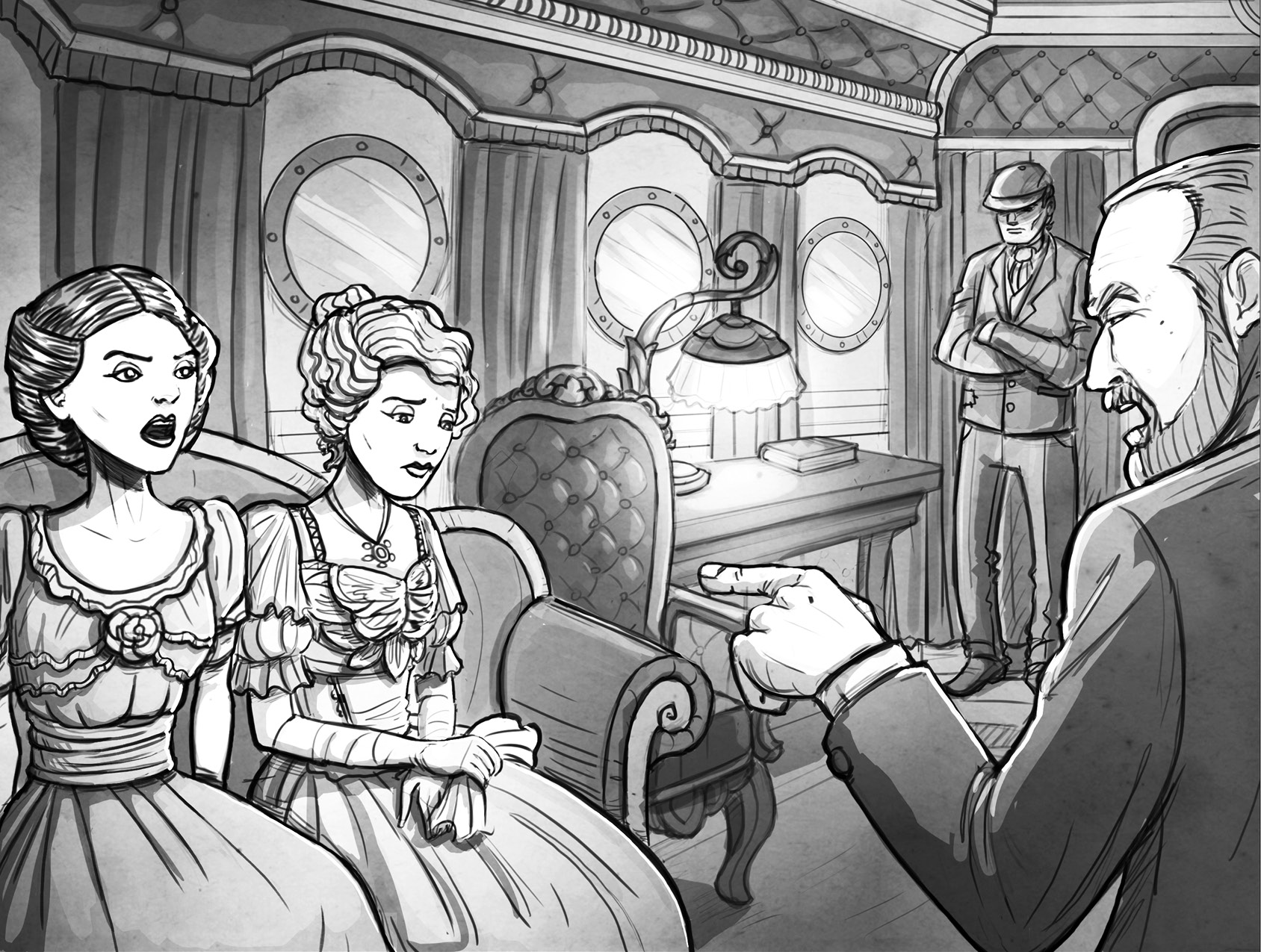

Three men in suits entered the room and slammed the door behind them. Two took up position on either side of the exit, while the thirdâa middle-aged man with graying hair and a sour expressionâremoved his hat and approached. Rosalind recognized him instantly as the grim-faced Inspector Bauer who had disrupted dinner the previous evening. He'd looked furious then, and he looked furious now.

“What is going on?” Rosalind demanded, starting to rise.

“Sit!” Bauer snapped.

Rosalind was tempted to stand on principle, but she doubted that it would do much good. Obeying, she replied, “What do you want?”

“I am Inspector Bauer of the Hamburg Police,” he answered, adjusting his tie.

“I know who you are,” Rosalind said, and she repeated her question more firmly: “What do you want?”

“I am responsible for security on the train,” Bauer told her. “And I have some questions to put to the both of you.”

“Is this about Cecily's death?” Rosalind asked.

“I will ask the questions!” Bauer barked.

Rosalind tensed, torn between outrage and grief. How dare he speak to her like that! Her friend was

dead

. Beside her, Alix cringed, and Rosalind wrapped her arms around the girl to comfort her.

“Now then,” Bauer said, “the two of you found the bodies?”

“Yes, that's right,” Rosalind replied. She tried to keep a civil tone, though all she wanted was to shout back at him, to demand to know how he could have let such a thing happen. But she held her tongue.

“And you are

. . .

?” Bauer asked.

“Rosalind Wallace.”

If Bauer recognized her name, he did not show it.

“Alix von Hessen,” Alix said softly.

“I did not hear you,” Bauer growled, as if he assumed Alix's meekness was born of truculence rather than of shock and sorrow.

“Alix von Hessen!”

Alix shrieked, burying her face in Rosalind's shoulder.

Bauer drew back. He muttered something under his breath. “You are related to the Grand Duke of Hesse?”

“My cousin,” Alix murmured.

“I see,” Bauer said quietly. He looked down at the floor, and then back up. “Perhaps you would care to retire to your compartment while I interview this young woman. There is no need forâ”

“ âThis young woman'?” Alix snapped, suddenly sitting up and squaring her shoulders. “No, I am staying with Rosalind while you ask your questions. She and I are

. . .

were

. . .

both friends of Cecily de Vere.”

Bauer cleared his throat. After a few moments of thinking, he nodded.

“Yes, well, good,” he said. “I have questions.” He looked at Rosalind. “Why was your friend on the train? What was her reason for traveling?”

It was such an absurd thing to ask that Rosalind was almost speechless. “She was on the train because she was going to America.”

“She is English,” Bauer said. “Why would someone from England take a German train when the English have so many ships, hmm? Answer that.”

“She came because I invited her,” Rosalind said.

“And

you

?” Bauer demanded. “Why did you come? What was your purpose in taking a German train?”

“It's an American train,” Rosalind snapped, with more hostility than she had intended. Bauer's tone, combined with the shock and stress, was making her blood boil. “It just happens to leave from Germany.”

Bauer frowned. “So you are American?” he asked. “And why were you in Europe?”

“I was visiting my

. . .

friend,” Rosalind said. “Cecily. Her.” She blinked a few times to force away the tears that were forming in her eyes. The full realization of Cecily's death was beginning to descend upon her. “I was staying with her family in London

. . .

”

“In London? Why would you travel from London to Hamburg to go to America? Hmm? Why not leave from England? It is suspicious.”

“Suspicious!” Rosalind cried.

“You and your English friend travel to Germany simply to take the Transatlantic Express?” Bauer said. He shook his head. “No, it is too unlikely. There must be a reason for it.” He took a step toward Rosalind, looking her up and down, his face creased in authoritarian anger. “So what is that reason?”

“Because her father owns the railway,” Alix said. She withdrew from Rosalind's embrace and stood. “Do you understand now?”

“Her father?” Bauer asked. He backed away from Alix and gave Rosalind a puzzled look. “Your father isâ”

“My father is Alexander Wallace,” Rosalind admitted, her voice taut and hoarse. Strange: in her bewilderment and grief, she had not even considered telling him who she was. Then again, nothing he'd done had made sense, so perhaps it wouldn't have made a difference. She couldn't understand why he was more intent on making her and Alix feel guilty than he was upset that their friend had been murdered. “You know, the man who built all of this,” she added.

Bauer took another step back. The color drained away from his face. He swallowed and set his expression, this time stony with professional detachment rather than openly hostile.

“Miss Wallace. Forgive me. I did not realize who you were.”

“I hardly see what difference it makes,” Rosalind said. “It shouldn't matter whether we're proper ladies or

. . .

or fishmongers' daughters! I want to know who killed my friend!”

Bauer held up his hands. He tried to look comforting, but it was a wasted effort. The twitch in his cheek betrayed his enraged frustration. He'd wanted to break Rosalind, and now he was suddenly forced to show subservience. “We are already looking into it,” he said. “We will find whoever is responsible, I give you my word. But in the meantime, you must be honest with me. Can you think of any reason

. . .

any reason at all

. . .

why a person might want to harm her?”

Rosalind exchanged a look with Alix. The very suggestion of it was absurd. A motive to kill Cecily? Cecily, of all people

. . .

“No, of course not,” she said.

“Cecily is

. . .

was a kind, gentle person,” Alix offered. “No one who knew her would want to hurt her, I am sure of it.” But then she turned to Rosalind and asked, “What about that man this afternoon?”

Before Rosalind could reply, Bauer stepped toward them again.

“What man?” he demanded.

Rosalind chewed her lip. Given that Cecily's murder made no sense to begin with, she supposed anything was possible. “There was a man who followed us when we took a walk around the station earlier today,” she explained to Bauer. “We confronted him

. . .

and he ran off.”

“Who was he?” Bauer asked. “Did you know him?”

“No,” Rosalind said. She shook her head vigorously. “None of us recognized him.”

“Describe him to me,” Bauer said.

“Um

. . .

” Rosalind thought for a moment. “Six feet tall, I think. No, shorter. Midthirties. Or maybe older. Dark hair. Small mustache. Brown suit and

. . .

and a bowler hat, if I remember.”

Alix nodded. “Yes, a bowler hat. I remember it. And the suit was very common. I think he was a tradesman.”

“He's a Second Class passenger,” Rosalind said. “I saw him return to a Second Class car on the train.”

Bauer looked away, apparently deep in thought. He slowly nodded a few times and muttered something to himself in German. Rosalind could not make out what he was saying.

“Very good,” he finally said. He bowed his head, formal and curt. “Ladies, I thank you for your time. We will sort the matter out, have no fear. In the meantime, I suggest that you remain in your compartments for the remainder of the evening.”

Rosalind nodded, as did Alix. “Yes, of course,” she said, almost mechanically. “Thank you, Inspector.”

Bauer motioned to the door. “My men will escort the two of you,” he said. “For your safety.”

Rosalind took Alix by the arm and went to the door. She looked back over her shoulder at Bauer and said, “You will find the person responsible, Inspector. Won't you?”

“You may trust in me, Miss Wallace,” Bauer said.

â¢â¢â¢

At Rosalind's compartment, under

the watchful eyes of Inspector Bauer's men, Alix embraced her tightly. Rosalind hugged her back for a long while. It was so strange that they had met only the day before. Alix was suddenly both her only friendâif one could even call her thatâand a terrible reminder of their friend's death, and would be for the duration of the journey. She could almost assume that Alix felt the same way. And how would they get word to Charles, to Cecily's parents? Would the Exham de Veres hold her accountable the way Inspector Bauer had?

“I will call on you tomorrow,” Alix said softly, stepping back.

“Thank you,” Rosalind said. “Try to get some sleep.”

“You, too, Rose.”

Rosalind closed the door on Bauer's men, leaning against it with her eyes closed. She took a deep breath and felt the coiled knot of anguish inside her come undone. Only then did she bury her face in her hands and weep.