The Third World War - The Untold Story (31 page)

Read The Third World War - The Untold Story Online

Authors: Sir John Hackett

Tags: #Alternative History

The day before the advance three further battalions were added to the divisional strength, in theory under Major General Pankratov’s command, in fact under the exclusive control of one Lieutenant Colonel Drobis of the KGB, the head of what was known at divisional headquarters as the Special Section. Two of these units were so-called KGB barrage battalions, manned by personnel of mixed origin with a relatively low degree of military training. There were cheerful, healthy looking young Komsomol workers alongside guards drafted from prisons and members of respectable bureaucratic families who had hitherto done little or no military service but whose engagement to the Party interest could be counted on as total.

The barrage battalions were equipped with light trucks and armed with machine-guns and portable anti-tank weapons. The function of these units was simple and their location in the forward deployment plan of the division in the attack followed logically from it. They were placed well up behind the leading elements to ensure, by the use of their weapons from the rear, that the forward impetus of their own troops was maintained and there was no hesitancy or slowing down, still less any tendency to withdraw. KGB fire power was an important element in the maintenance of momentum. This caused losses, of course, but these would be readily compensated for in the arrival of fresh follow-up formations, so that the net gain could always be reckoned worthwhile. The use of KGB barrage battalions to stimulate offensive forward movement was, moreover, an essential element accepted without question in the Red Army’s system of tactical practice in the field. This was wholly oriented to the offensive. Defence played virtually no part in it at all and offensive impetus had to be maintained.

Total refusal to countenance withdrawal could, of course, at times be costly. On the first day of the offensive two tank battalions of 174 Tank Regiment, moving forward from out of woodland cover, were caught almost at once in open ground by heavy anti-armoured air attack from the United States Air Force. Temporary withdrawal into cover, which was all that made sense, was flatly forbidden by the KGB. When the attacking aircraft themselves withdrew, tank casualties on the ground were in each battalion over 80 per cent.

The progress of 51 Tank Division in the attack on 6 August had been slower than hoped for, it’s leading battalion hammered by United States anti-tank weapons in front, against the anvil of the KGB behind.

Of the three special KGB battalions attached to 51 Tank Division, the third was 693 Pursuit Battalion. This followed up in the advance rather further back. Its business was the liquidation of possibly hostile elements in the local population - any who were obviously reactionary bourgeois, for example, or priests, or local officials - as well as taking care of officers and men of 51 Tank Division who had shown insufficient fighting spirit.

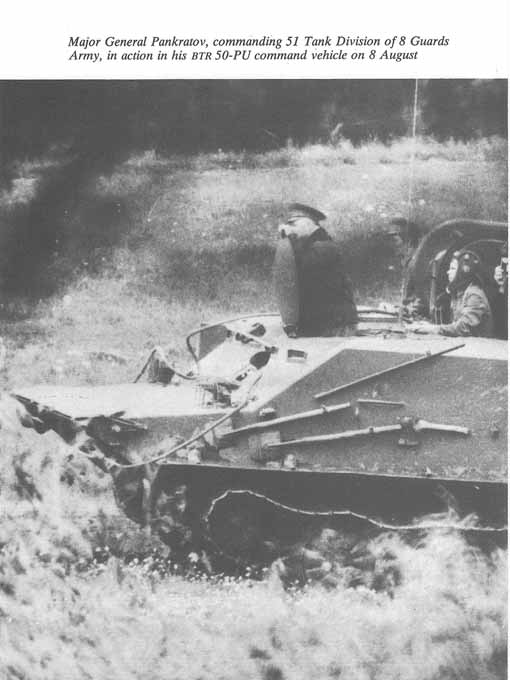

The divisional commander stood at the operations map in the BTR 50-PU which formed his command centre. On his right stood his political deputy, a Party man; on his left, his chief of staff; behind him Lieutenant Colonel Drobis of the KGB. Colonel Zimin, commanding the divisional artillery, was just climbing down into the BTR, closing the hatch firmly behind him. It was late afternoon on 6 August.

“An important task for you, Artillery,” growled the divisional commander. “We’ve got a valley here between two hills with a road along the valley leading towards us. We tried to break through there yesterday, but got our fingers burnt. We start to attack and the Americans bring far too effective anti-tank fire along that road from positions further back.

“If they try that again this time your BM-27 multiple rocket launcher battalion will take them out. They have to be suppressed in one go. So there’s a prime task for you for tomorrow.”

“Comrade General,” replied the artillery commander, “permission to move the BM-27 battalion 5 kilometres back and another 5 to the south?”

“Why?” barked Lieutenant Colonel Drobis, breaking in.

“It’s a question of ballistics, of the laws of physics,” explained Colonel Zimin patiently. “We fire off several hundred rounds at a time. We want to cover a road which is at right-angles to the front - so the impact zone has to be spread along the road, not across it. Our present firing positions are too far forward and too far to one side to do this. So we have to fire from further back, and further to the south. We move back, fire and move forward again.”

“In no circumstances,” snapped the KGB Lieutenant Colonel, “none at all. You stay where you are and fire from there.”

“But then the zone will lie across the road instead of along it.”

“Then try to get it along the road.”

“I can’t do that from the present firing position, only 2 kilometres from the front line and 5 from the axis of the road.”

“You want to retreat?”

“It’s essential to move back at least 5 kilometres and 4 or 5 kilometres further south if the tank regiment is to break through.”

“You go back to the rear, while we’re in the thick of it up here? Listen Colonel, you get your zone, or whatever you call it, along the road from the front line or ...”

“It’s ballistics, Comrade. Our fire pattern depends on the laws of ballistics. We can’t make those up as we go along.”

“Right. No more of this. I won’t allow you to retreat, and you refuse to carry out orders. Arrest him! You can discuss this further where you’re going.”

Two KGB sergeants pinioned Colonel Zimin’s arms and dragged him out.

General Pankratov went on looking stolidly at the wall map, keeping out of this skirmish between the artillery chief and the head of the Special Section. The divisional commander could see that another disaster was due in a few hours. He knew that, for all the theory of offensive action upon which it was based, tomorrow’s attack would get bogged down again just like yesterday’s and for the same reason. He was sad not to be able to do anything to protect the artillery commander, who was an old friend, but he knew that it would be useless to try.

Many years ago, when the General was still a young lieutenant, he was puzzled at the irrational, even, he used to think, the idiotic way in which so much was done in the Red Army. It was not till he was studying at the Frunze Military Academy that he was able, with greater maturity and more experience, to take a closer look at the Soviet power structure. He saw it not the way it was theoretically said to be, articulated under an exemplary constitution, but the way it was in actual naked fact, a structure serving one end only, the perpetuation of the supreme power of the Party. It was also true that other elements in the composition of the USSR were more interested in the preservation of structures which embodied personal power than in their functional efficiency.

The Red Army was the only organized power grouping in the Soviet Union capable of destroying the entire socialist system without harming itself. It was scarcely surprising therefore that in every battalion, regiment and division, in every headquarters at any level, in every military establishment, the Party and the KGB kept keen and watchful eyes on all that went on. There was a Party political officer in every Soviet company, in the post of deputy commander. There were KGB secret agents in every platoon.

The KGB and the Party realized (for these were not all stupid men) that such close control kills initiative and contributes to a dullness of performance which in an army invites defeat. But what could they do about it? If they did not keep control of the army it would devour them. Here, as many realized, was a clear dilemma. An army which is allowed to think holds dangers for socialism. An army which is not allowed to think cannot be an efficient fighting force. The Party and the KGB, faced with a choice, as they saw it, between an efficient army which could threaten their own position, and an army which constituted no threat but was unlikely to give a good account of itself in battle, chose what they saw as the lesser of two evils. When war came it was even more dangerous to loosen controls on the army than in peacetime. The interference of amateurs in the persons of Party bureaucrats and the secret police in such highly professional matters as the conduct of military operations was certain to cause mistakes and even lead to disaster, but this was clearly far better than letting the army off the leash and out of Party control.

General Pankratov, a high-grade professional, was quite confident he knew how to break up an American division. Neither the KGB men nor the Party stool pigeons knew how to do this and it was not possible to show them, for they were not professional soldiers. They would mouth their Party platitudes and act according to their secret instructions. They would always, of course, have to have the last word. Tomorrow, therefore, General Pankratov would do what they wanted, without any choice, and also without either originality or initiative. He would attack the enemy head-on, for this was the only way his controllers thought a battle could take place. If he did anything else he would be killed and a new commander would take over the division. A newcomer would almost certainly act in a way that the stool pigeons from the political department and the suspicious, watchful “Comrades” from the Special Department understood. If he did not, he too would be killed and another replacement found and this would go on until a commander was found who could easily be controlled and whose every move would be easily understood by everyone.

Nothing, General Pankratov reflected, could be changed. The orders he would have to give for tomorrow’s battle would be foolish ones. Soldiers, of course, would now yet again be sent to a wholly purposeless death.

Quite apart from these personal and somewhat philosophical reflections, the General was also worried over some strictly professional matters. He had found it very difficult to relate the action of motor rifle infantry in BMP to movements of the tanks with which they had to co-operate. The vehicles moved at different speeds. The BMP were highly vulnerable to even light attack from gun or missile. The riflemen were often more effective dismounted than in their vehicles, in spite of the additional armament these carried. On their feet, however, they could not keep up with the tanks and were weak in fire power. It was increasingly the case, therefore, that tanks either came to a halt because they had out-run the infantry, or moved on into anti-tank defences which there had been no infantry at hand to suppress.

Moreover, General Pankratov was again finding himself travelling round the old vicious circle. He could not call for air support unless the progress his attack had made had earned him preferential treatment over other divisions in the army. As he had already discovered, it was sometimes impossible to make the progress required to qualify for air support unless you had it in the first instance. The inflexibility of battle procedures was a good match for the tight restrictions placed upon a commander’s action by the Party. The two together made an almost certain formula for disaster, which was only kept at arm’s length by the enormous weight of forces the Red Army had available and the staggering degree to which the common soldier accepted casualties.

General Pankratov looked up from the tank, vehicle and ammunition states which had just been given to him - none of which made any more cheerful reading than the personnel strength and artillery states he had already seen - and in a tired and indifferent voice gave the orders for tomorrow’s battle.

He would go into action in his command vehicle, wearing a peaked military cap, as always. Steel helmets were hard on the head and difficult to manoeuvre in and out of hatches. If his BTR 50-PU were hit by anything that mattered, a steel helmet would be of no help anyway. General Pankratov, like most generals anywhere, was something of a fatalist.”*

* He survived the war. What has been set out here was learned in a personal interview with ex-Major General Pankratov in the summer of 1986 in his home town of Vyshniy-Volochek between Petrograd and Moscow.

The performance of Warsaw Pact formations had not in some important respects proved entirely satisfactory to the Soviet High Command. Co-operation between arms had been incomplete. Artillery support had been slow in response and inflexible. Junior command had been lacking in thrust, relying too much on guidance from above. The Western allies had been quick to exploit this weakness, applying their excellent electronic capabilities to the identification of command elements which they then often managed to take out. Coherence in units, in spite of the close attention of KGB barrage battalions, had not been high, often because of the low level of reservist weapon skill and the great difficulty in achieving co-operation between men who could not understand each other’s languages. Finally, there was the greater difficulty of co-ordinating infantry and tanks in action. Only infantry, in the long run, could effectively put down anti-tank defences, however powerful the assistance of technical aids to suppressive action by artillery and fixed- and rotary-wing aircraft. The tanks were highly vulnerable to unsuppressed and well-sited ATGW, as well as to long-range fire from very capably handled Allied tanks. Without infantry the tanks of the Warsaw Pact were at a severe disadvantage. But the BMP was even more vulnerable than the tank, as well as being unable to move over the country at the same speed. It very quickly became Allied practice to try to separate infantry from tanks and this was often highly successful.