The Third Reich at War (23 page)

the English are continuing to leave, even from the open coast! When we finally get there, they will be gone! The Supreme Leadership’s halting of the tank units has proved to be a serious mistake! We continue attacking. The fighting is hard, the English are as tough as leather, and my divisions are clapped out.

40

As the battle finally drew to a close, Bock paid a visit to the scene. He was surprised by the quantity of concrete bunkers and barbed-wire defences that guarded Dunkirk, and dismayed by the quality of the enemy’s equipment:

The English line of retreat presents an indescribable appearance. Quantities of vehicles, artillery pieces, armoured cars and military equipment beyond estimation are piled up and driven into each other in the smallest possible space. The English have tried to burn everything, but in their haste have only succeeded here and there. Here lies the

mate’riel

of a whole army, so incredibly well equipped that we poor devils can only look on it with envy and amazement .

41

Two days later, Dunkirk finally surrendered. 40,000, mostly French, troops, who formed the rearguard, were left behind to be taken prisoner. Weygand blamed the British for leaving his men behind, though the evacuation had in fact continued for two days after the last British soldiers had left the beach. In any event, the choice of the French to form the rearguard was a natural one given their relatively late arrival on the scene. Nevertheless, Weygand raged bitterly at Churchill’s refusal to send any more aircraft or troops to the defence of France. The British in their turn, determined now not to compromise the defence of the British Isles by sacrificing any more of their armed forces or planes, were contemptuous of the French generals and political leaders, whom they regarded as over-emotional, weak and defeatist. British generals did not burst into tears, however dire the situation they were in. Relations were approaching rock-bottom. They were not to recover for some time.

42

After regrouping, repairing and recovering, the Germans began advancing south with 50 infantry divisions and 10 admittedly somewhat depleted panzer divisions. Forty French infantry divisions and the remnants of three armoured divisions stood in their way. On 6 June 1940 German forces crossed the Somme. Three days later they were in Rouen. The French government had been evacuated to a series of chaˆteaux dotted around the countryside south of Paris, where communications were difficult, working telephones rare, and travel made almost impossible by the endless columns of refugees now clogging the highways. On 12 June 1940, at their first meeting since leaving Paris, the shocked ministers were told by Weygand that further resistance was useless and it was time to request an armistice. In Weygand’s view, the British would not be able to hold out against a German invasion of the United Kingdom, so evacuating the French government to London was pointless. Moreover, like an increasing number of other generals, Weygand was beginning to think that it was the civilian politicians who were to blame for the debacle. So it was the army’s duty to make an honourable peace with the enemy. Only in this way would it be possible to prevent anarchy and revolution breaking out in France as it had after the previous defeat by the Germans, in 1870, and spearhead the moral regeneration of the country. The hero of the Battle of Verdun in the First World War, the aged Marshal Philippe P’tain, had been brought in as a military figurehead by Reynaud, and he now backed this idea. ‘I will not abandon the soil of France,’ he declared, ‘and will accept the suffering which will be imposed on the fatherland and its children. The French renaissance will be the fruit of this suffering . . . The armistice is in my eyes the necessary condition of the durability of eternal France.’

43

On 16 June 1940, after the government had reconvened in Bordeaux, Reynaud, isolated in his opposition to an armistice, resigned as Prime Minister. He was replaced by Pe’tain himself. On 17 June 1940 the new French leader announced on public radio that it was time to stop the fighting and sue for peace. Some 120,000 French soldiers had been killed or been reported missing in the conflict (along with 10,500 Dutch and Belgian, and 5,000 British), showing that many did fight and belying claims that French national pride had been destroyed by the politics of the 1930s. But after Pe’tain’s announcement, many gave up. Half of the 1.5 million French troops taken prisoner by the Germans surrendered after this point. Soldiers who wanted to fight on were often physically attacked by civilians. Conservatives like P’tain who abhorred the democratic institutions of the Third Republic did not see in the end why they should fight to the death to defend them. Many of them admired Hitler and wanted to take the opportunity of defeat to re-create France in Germany’s image. They were soon to be given the opportunity to do so.

44

V

Meanwhile France was descending into almost total chaos. A vast exodus of refugees swept southwards across the country. An ’migr’ Russian writer, Irène N’mirovsky, who had fled the Bolshevik Revolution to go to France in 1917 at the age of fourteen with her Jewish businessman father, vividly described ‘the chaotic multitude trudging through the dust’, the luckiest pushing ‘wheelbarrows, a pram, a cart fashioned of four planks of wood set on top of crudely fashioned wheels, bowing down under the weight of bags, tattered clothes, sleeping children’.

45

Cars tried to move along the clogged roads, ‘full to bursting with baggage and furniture, prams and birdcages, packing cases and baskets of clothes, each with a mattress tied firmly to the roof’, looking like ‘mountains of fragile scaffolding’. ‘An endless, slow-moving river flowed from Paris: cars, trucks, carts, bicycles, along with the horse-drawn traps of farmers who had abandoned their land’.

46

The speed and scale of the German invasion meant there were no official plans for evacuation. Memories of German atrocities in 1914 and rumours of the terrifying effect of bombing created mass hysteria. Whole towns were deserted: the population of Lille is thought to have fallen from 200,000 to 20,000 in a few days, that of Chartres from 23,000 to 800. Looters broke into shops and other premises and took what they wanted. In the south, places of safety were swollen to bursting with refugees. Bordeaux, usually home to 300,000 inhabitants, doubled in population within a few weeks, while 150,000 people crammed into Pau, which normally housed only 30,000. Altogether it is thought that between 6 and 8 million people fled their homes during the invasion. Social structures buckled and collapsed under the sheer weight of numbers. Only gradually did people begin to return to their homes. The demoralization had a devastating effect on the French political system, which, as we have seen, fell apart under the strain.

47

When the Germans entered Paris on 14 June 1940, therefore, they found large parts of it deserted. Instead of the usual cacophony of car horns, all that could be heard was the lowing of a herd of cattle, abandoned in the city centre by refugees passing through from the countryside further north. Everywhere they went in France, German troops looted the deserted towns and villages. ‘Everything’s on offer here, just like in a big department store, but for nothing,’ reported Hans Meier-Welcker from Elbeuf on 12 June 1940:

The soldiers are searching through everything and taking anything that pleases them, if they are able to move it. They are pulling whole sacks of coffee off lorries. Shirts, stockings, blankets, boots and innumerable other things are lying around to choose from. Things that you would otherwise have to save up carefully for can be picked up here on the streets and the ground. The troops are also getting hold of transport for themselves right away. Everywhere you can hear the humming of engines newly turned on by drivers who still have to become familiar with them.

48

The French humiliation seemed complete. Yet there was worse to come. On Hitler’s personal orders, the private railway carriage of the French commander in the First World War, Marshal Foch, in which the Armistice of 11 November 1918 had been signed, was tracked down to a museum, and, after the museum walls had been broken down by a German demolition team, it was moved out and towed back to the spot it had occupied in the forest of Compiègne on the signing of the Armistice. As the Germans arrived, William L. Shirer noted Hitler’s face ‘brimming with revenge’, mingled with the triumph observable in his

‘springy step’. Taking the very same seat occupied by Foch in 1918, Hitler posed for photographs, then departed, contemptuously leaving the rest of the delegation, including Hess, G̈ring, Ribbentrop and the military leaders, to read out the terms and receive the signatures of the dejected French.

49

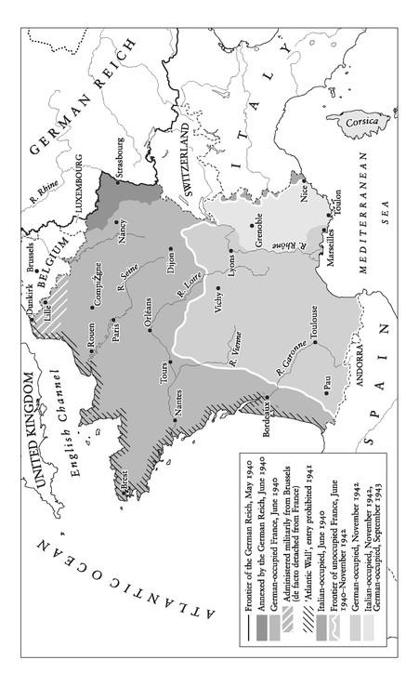

In accordance with this agreement, all fighting ceased on the morning of 24 June 1940. France was divided into two, an occupied zone in the north and west, with a nominally autonomous state in the south and east, run from the spa town of Vichy by the existing government under Marshal P’tain, whose laws and decrees were given validity throughout the whole of the country.

50

German forces had performed the greatest military encirclement in history. No subsequent victories were to be as great, or as cheap in terms of German lives, of which fewer than 50,000 were lost (killed or missing). More prisoners, almost a million and a half, were taken than in any other single military action of the war. The success persuaded Hitler and the leading generals that similar tactics would bring dividends in future actions, notably, the following year, in the invasion of the Soviet Union.

51

Germany’s hereditary enemy had been humiliated. Versailles had been avenged. Hitler was beside himself with elation. Before dawn on the morning of 28 June 1940, he flew secretly to Paris with his architect Albert Speer and the sculptor Arno Breker on a brief, entirely personal sight-seeing trip. They visited the Ope’ra, specially illuminated for his benefit, the Eiffel Tower, which formed the backdrop for an informal photo of the three men taken at first light, the Invalides and the artistic quarter of Montmartre. ‘It was the dream of my life to see Paris,’ Hitler told Speer. ‘I cannot say how happy I am to have that dream fulfilled today.’ Pleased with the visit, he revealed to the architect that he had often thought of having the city razed to the ground. After the two men’s grandiose building plans for the German capital had turned it from Berlin into the new world city of Germania, however, he said later, ‘Paris will only be a shadow. So why should we destroy it?’

52

Hitler never returned to the French capital. The victory parade was to take place at home. On 6 July 1940 vast, cheering crowds lined Berlin’s streets, upon which people had strewn thousands of bouquets of flowers along the route to be taken by the Leader from the station to the Chancellery. Upon arriving there, he was repeatedly called out onto the balcony to receive the plaudits of the thousands gathered below. There had, as William L. Shirer noted, been little excitement when the news of the invasion of France had been announced. No crowds had gathered before the Chancellery, as usually happened when big events occurred. ‘Most Germans I’ve seen,’ he noted on 11 May 1940, ‘are sunk deep in depression at the news.’

53

As in previous foreign crises, there had been widespread anxiety about the outcome, underpinned by a general fear at the possibility of Allied bombing raids on German cities. But as on previous occasions too, relief at the ease with which Hitler had achieved his objective flowed together with feelings of national pride into a wave of euphoria. This time it was far greater than ever before. Not untypical was the reaction of the middle-class history student Lore Walb, born in 1919 in the Rhineland and now at Munich University. ‘Isn’t that tremendously great?’ she asked rhetorically as she recorded the victories in her diary on 21 May 1940. She put it all down, as many did, to Hitler: ‘It’s really only now that we can truly estimate our Leader’s greatness. He has proved his genius as a statesman but his genius is no less as a military commander . . . With this Leader, the war cannot end for us in anything except victory! Everyone’s firmly convinced of it.’

54

7. The Partition of France, 1940

‘Admiration for the achievements of the German troops is boundless,’ reported the SS Security Service on 23 May 1940, ‘and is now felt even by people who retained a certain distance and scepticism at the beginning of the campaign.’

55

The capitulation of Belgium, the reports continued, ‘prompted the greatest enthusiasm everywhere’, and the entry of German troops into Paris ‘caused enthusiasm amongst the population in all parts of the Reich to a degree that has not so far been seen. There were loud demonstrations of j oy and emotional scenes of enthusiasm in many town squares and on many streets.’

56

‘The recent enthusiasm,’ it was reported on 20 June 1940, ‘gives the impression every time that no greater enthusiasm is possible, and yet with every fresh event, the population gives its joy an even more intense expression.’ Pe’tain’s announcement that the French were throwing in the towel was greeted by spontaneous demonstrations on the squares of numerous German towns. Veterans of the First World War were amazed at the speed of the victory. Even those opposed to the regime confessed to a feeling of pride, and reported that the general atmosphere of j ubilation made it impossible to continue their underground resistance activities, such as they were.

57

The Catholic officer Wilm Hosenfeld, who had been so critical of German policy in Poland that he had written to his wife that ‘I have sometimes been ashamed to be a German soldier’,

58

was swept away by the news: ‘Boy oh boy,’ he wrote to his son on 11 June 1940, ‘who wouldn’t have been happy to have taken part in it!’

59

In Hamburg, the conservative schoolteacher Luise Solmitz shared in the general euphoria: ‘A grand, grand day for the German people,’ she wrote in her diary on 17 June 1940 on hearing the announcement that P’tain was suing for peace. ‘We were all exhilarated by happiness and enthusiasm.’ The victory was