The Third Person (9 page)

Authors: Steve Mosby

A few minutes’ walk took me to a quieter section of the city, where the canal snakes through at the edge. Graham’s building backed onto the canal, which is why the three lower floors remained entirely unoccupied. When the industrial skies open over winter, the abandoned canal overflows, filling nearby buildings to an admirable height and washing away any derelicts that have managed to squeeze in through the cracks. Of course, it doesn’t make any difference to the high-flyers on the floors above: for them, the canal is just this picaresque thing from another era; it’s no different to having an old, golden barometer

on the wall, or a three-hundred-year-old wooden chest to put their dirty laundry in. When the banks flood, it just gets a few metres closer and they can see it better. That’s all.

The intercom on the front of the building looked like something you’d put a cigarette out on – and, if you did, it probably wouldn’t have left a mark. Cars shot past behind me as I tapped in seventeen-twelve and in the pause that followed, I turned and looked around. Busy road. Perfectly-styled park over the other side. A deli further up, painstakingly recreated. There was probably even a nice little church around here somewhere: a church without a door. When we were teenagers, Graham had told me:

life’s just a lot of fakery and bullshit, and I hate it

. What had happened to my friend?

I heard the voice come out of the intercom and turned back.

‘Hello?’

His voice, and yet not. All the intercoms in the city centre sound exactly the same: it’s a lightly amplified, disguised male voice. Imagine a vaguely pissed off robot. For all I knew, it was Helen answering the door, but I took a gamble that it wasn’t.

‘Gray,’ I said, leaning in. ‘It’s Jason.’

A pause.

‘Hijay.’ Our old amalgamated greeting told me it was him. ‘Come on up. Wait; hang on.’

The intercom was muffled for a few seconds. I could hear that he was talking to Helen, but couldn’t make out the actual words. Of course, I didn’t really need to.

A moment later, the intercom cleared.

‘Come on up.’

The latch on the steel door buzzed loudly for a couple of seconds, as though in warning, and then clicked open. I pushed it and went inside, and was immediately hit by the smell of fresh pot-pourris that filled the stairwell. This was such a nice apartment block.

The elevator was already on its way down for me. I waited

for it to arrive, already sure that this was going to be a tense morning.

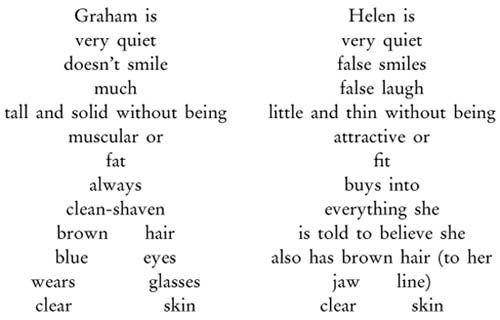

A couple of picture portraits.

Those are the facts – but even there they’ve come out uneven, because the facts about Helen are more difficult to pin down. Nobody would ever deny the things I’ve said about Graham – what you see is what you get – but Helen’s a far more subjective prospect: it’s difficult to pin down anything concrete and personal about her, because she’s totally absorbed in the relationship.

Certain things are true, of course. She is small (five foot) and thin (probably about seven stone), and she does have clear skin, in the same way that a baby has a clear conscience; these aren’t things she’s ever had to work at. In fact, she’s never had to work at anything, as far as I know. Her parents are both very rich and very protective: a lethal combination. They paid her way through University, and then supported her for a while afterwards, all the time assuming that their investment

in her gave them overall control on any decisions she had to make. If you wanted to see Helen as a company, you might see her parents as two silent partners who between them have the casting vote. You would have to see her as a small company, of course, but keep that a secret from the silent partners: they see it as a world-beater.

What would this company do? It’s simply not streamlined for business and knows it. So it merges. There is strength in numbers, and it makes sense for the weak to ally themselves with the strong. The silent partners – who, having organised it themselves, don’t understand how weak the original corporate structure is – see it the other way around.

Merge by all means, they explain,

but never forget

who is the

most important and dominant company in this merger

.

I’d been friends with Graham since we were little kids; our families lived next door to each other and we got on from day one – peas in a pod, and all that. Except he was always more brilliant than me academically, while I outshone him socially. When I was already happily esconced with Amy, he’d never even had a girlfriend.

What about Helen

? Amy asked me one day. Helen was a childhood friend of Amy’s, but the revolutions of our social circles were such that Graham and Helen had yet to actually meet.

What do you think about them as a couple

? I thought it sounded cool. I wanted Graham to be happy: he’d been growing increasingly insecure and introspective as time went by, and it was starting to worry me. Helen seemed nice.

Is

nice, really, in her own way.

So we introduced them and encouraged them.

Madness.

On the one side, Graham: a genuinely nice, shy guy who – despite his notable success in several key areas of life – had begun to feel like an abject failure because he didn’t meet the marketed standard of shagging hundreds of women and having relationships which, the movies had assured him,

would provide him with that all-important reason to live. On the other side, Helen. She was desperate for a relationship in much the same way, but her subconscious feelings of inadequacy – so well-covered by those false smiles and that cheery disposition – were bubbling up, convincing her that she would never get one.

The way I saw it was this: when you’re falling through the air, you don’t pick and choose your handholds; you grab onto the first branch you can get your fucking hands on, and you cling to it with grim determination. And they were both falling. Putting them together was only ever going to end one way: in a kind of awful, successful failure.

‘Hi, Jason.’

Helen peered around the edge of the door like an anxious child, giving me a big smile. She was one of those people who had to say everything with a laugh and a joke. The subtext every time she opened her mouth was always the same:

things are spiralling out of control

, she was saying,

but you have to laugh, don’t you

?

‘Come on in.’

‘Cheers.’ I wandered into the hall. ‘How are you doing?’ Being quite small, Helen was also quite weak, and she had to push the door quite hard to get it closed. The effort was there in her voice:

‘Oh – just pottering. You know.’

She laughed.

‘Gray in?’ I said.

‘Through in the study.’ She raised her eyebrows by flicking her head back: a Helen tut. ‘Working. As usual.’

‘Keeping you in the manner to which you’ve become accustomed,’ I said, smiling. It was half a joke, with neither half being particularly funny, but she laughed anyway.

‘Well, yes.’ The arms went out in a shrug.

What can I do

?

I gestured with my thumb. ‘I’ll just go on through?’

‘Sure, go on. He’s expecting you. Coffee?’

‘That’d be great, yeah.’

I meant it, too. Look – don’t get me wrong about this. As a friend, I didn’t dislike Helen. In fact, in a lot of ways she was lovely: anybody who offers you coffee as a matter of course is okay by me, and – in general – she was personable enough. I just didn’t think she was right for Graham. Nobody thought that, even, I suspect, Helen and Graham, and – coffee and smiles aside – that’s a pretty fucking significant detail. You can have a relationship with anyone, after all, but despite what the books and the movies might tell you, a relationship is not, in itself, what you need. What you need is to add some qualifiers. ‘

Good

’, in the middle of that phrase, for one. And while we’re on the subject, ‘

that you really want

’ at the end is also an idea.

I made my way through to the study, where heavy industrial music was grinding away quietly in the background. In the kitchen, Helen would be listening to glitzy, gloss-sheen pop – slightly despairingly. On the cupboard above the kettle there was an a4 sheet listing the names of friends and how each friend liked their tea and coffee. By my name, it would say

white, two sugars, black, no sugar

. She’d run her finger over it and tap.

Ah ha

.

Whereas I’d known Graham for years, but he still had to ask me – and I don’t know why that’s better but for some reason it is. Maybe I’m just suspicious that if you concern yourself too much with little details, there’s no mental space left for the more important stuff.

He leaned back in his chair as I entered the study, putting his big hands behind his head, yawning and stretching. Then, he gave me a smile.

‘Hi mate. How are you doing?’

‘I’m okay, yeah,’ I said, wandering over and taking a seat

beside him. In front of him, his computer was chugging through what was, no doubt, another mindless search. ‘How’s tricks?’

‘Ticking over.’

‘You’re busy?’

‘I’m always busy. Is Helen making you a cup of coffee?’

‘I think so, yeah.’

‘Nice to know the bitch is good for something.’ He closed two search windows down with a click of the mouse, and then set another three tumbling. ‘She’s been doing my head in this morning. All morning.’

Every morning

.

I remembered parties where Helen would talk to Amy and Graham would come into the kitchen to talk to me, and they’d both say the equivalent of the same thing:

goddamn, my juicy burger is squashed and wet and fucking miserable. I can’t believe I paid a pound for this shit

.

I said, ‘Getting on your case?’

‘Exactly. I mean, I have work to do. She wants to play house.’

‘Want me to get out of your hair?’

‘No, it’s okay.’ He clicked the mouse again. ‘I can talk while I work. I just can’t Ikea. Or at least I won’t.’

He typed in a few words, his fingers as lightning fast as ever.

cola boy coat shoe light [RETURN]

‘Just give me a minute. On top of all the work I have to do, I’m also trying to download the new Will Robinson single from Liberty. To keep her happy.’

‘That would keep anyone happy.’

‘Well, obviously. So just give me a minute.’

‘Okay.’

I looked around while he worked. The study was incredibly old- fashioned, especially given the industry he worked in. As a contrast to the spare, metallic feel of the rest of the flat, this room was decked out in dark wood, with crammed bookcases

lining three of the walls, while the other was taken up by the console he was working at. The books themselves were old – classics mostly – with modern reference texts and manuals dotted around, their vibrant spines standing out. You could buy bookcases like these from lifestyle catalogues – I think there were about twenty or so on the market – and save yourself the bother of collecting and reading a lifetime’s supply of literature: you just ordered the bookcase and it came ready-stocked, making your study look authentic and used. I could have been on a ship, or in a Victorian drawing-room.

In the centre of the room was an old table with battered, bowed legs. A series of printed paper sheets was spread upon it, with more paper slipping out of the printer hatch in the wall no doubt soon to join it. This was Gray’s job: professional web gopher. He was one of the most respected information-ferrets in the business, employed by a number of well-known companies and individuals to hunt down details of rival products, research projects, other individuals and then produce easy-to-read reports on what he’d found.

And he was good at his job. The approach he had to the internet was one of Zen interconnectedness. All the information is linked together in a web, he figured, and every little bit of information affects all the others. According to chaos theory, a butterfly flapping its wings can eventually affect weather systems on the other side of the planet. Graham had taken this to heart, and he’d applied the science of it to the web, at first by trial and error and then – as he learned more – by developing systems and approaches. Nowadays, with the internet, he was that butterfly. He flapped his wings in significant little ways that only he understood, and the information he wanted came blowing in from the east. One day, he told me, he was going to write a book and become enormously rich.

After a minute or two, Helen brought a mug of coffee in

and passed it to me, along with a cork coaster. I smiled and said thanks, and she left. Graham looked a little resentful.