The Third Day (15 page)

Authors: David Epperson

We watched the soldiers work for another half hour before a young man wearing sandals and a plain brown tunic approached and beckoned for us to follow. He led us to the southeast corner of the fortress and started up a flight of stairs, taking the steps two at a time all the way to the top.

Except for Bryson, we all made it with a minimum of huffing and puffing. It had to be a test, though of what I wasn’t sure; nor could I know whether or not we had passed.

The kid waited patiently at the top landing for the Professor to catch up before leading us down a short corridor and inserting a key into a thick wooden door.

He gestured for us to go inside.

The room was larger than I had expected – about fifteen by thirty feet. The walls were built of the same

meleke

limestone as the rest of the fortress, with thick cedar beams running across the ceiling. Four windows, each about three feet wide, faced the Temple courtyard to the south, while two narrower windows opened to the west, giving the room a red glow from the late afternoon sun.

The furniture was sparse, but functional, as I would have expected in a military establishment. A large bed, wider than king-sized by half, sat in the northeast corner of the room, away from the windows. A wooden table, surrounded by six crude-looking chairs rested in the center.

“What’s that?” Sharon asked, referring to a bucket on the floor in the far corner, opposite the bed.

I couldn’t help but laugh. “Piss pot,” I replied.

She blushed. “Oh.”

“Go, if you have to. We’ll all turn the other way.”

She was about to speak when the young man said something to Lavon.

It must have been about food, because after hearing the archaeologist’s response, the man shouted down the stairs. A few minutes later, two slaves appeared carrying warm bread and a jug of wine, followed by two more servants holding five metal goblets and a stack of blankets. The men deposited their cargo without speaking and immediately turned for the door.

After the kid left, I motioned for everyone to gather around the table for a de-brief but quickly realized that it was hopeless. Each of the others raced for a window, where they stood mesmerized by the activity in the Temple courtyard below.

From our vantage point near the top of the southeastern battlement, we could see white-robed priests – drawn by lottery earlier that day – as they completed the evening offering and prepared the Temple for the night.

Each man was dressed identically in a white linen tunic, with a red belt and white linen, turban-like headgear. To our surprise, the priests went about their tasks barefoot.

Bryson edged himself out and around the sill of the far left window in an effort to get a better view.

“Fascinating,” he muttered to himself. “Utterly fascinating.”

It most assuredly was.

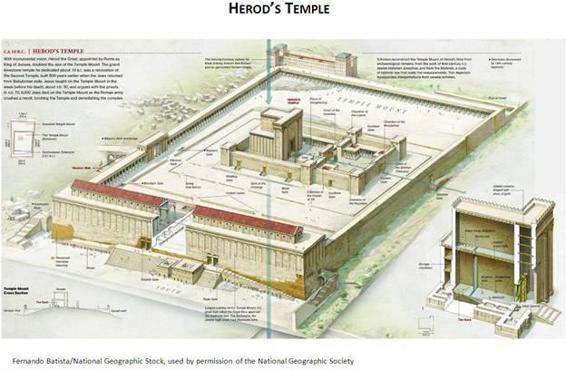

The Temple itself faced to the east and was situated slightly south of center on the broad rectangular Temple Mount, whose flat white surface covered about thirty five acres. From our position, only a few feet below the Temple roof, the setting sun highlighted the gold edging in a spectacularly beautiful way.

Lavon peered straight down and broke out in quiet mirth.

One of his old college professors had published a paper asserting that the Antonia was an integral part of the Temple complex, while a colleague had just as emphatically maintained that the fortress was situated about six hundred feet to the north, connected to the Temple only via breezeways.

In the manner of so many obscure academic quarrels, their dispute had become so bitter that despite having offices in the same building, neither man spoke to the other for more than two years.

Both of them were wrong.

Herod’s engineers had been clever, we could see. They had located the south wall of the Antonia about thirty feet from the Temple Mount’s perimeter. A system of gates and bridgeways permitted the easy flow of soldiers and materiel from the fortress to the Temple, but would present an almost insurmountable obstacle to anyone trying to get through the other way.

“They appear to know what they’re doing,” I said – and not for the last time.

Lavon nodded; then he looked up and saw that Bryson had eased himself dangerously close to the window’s edge. To make matters worse, we could see the bright red LED on his camera.

Lavon coughed. “Ahem; Professor, you might not want anyone to see you with that thing.”

To his credit, Bryson quickly realized his mistake and eased himself back inside.

“By the way,” I asked. “How much battery life do you have left?”

Bryson squinted at the small screen. “Three hours; that should be enough.”

Lavon wasn’t so sure. The Gospels recorded only that the body was gone by the time the women arrived around dawn on Sunday morning. None of them set forth a precise chronology as to when the actual event had occurred.

“Did you bring any spares?” I asked.

“Two.”

“Do you still have them?”

Bryson smiled as he felt for the small pouch he had tucked into his tunic. His expression, though, quickly changed to one of worry and embarrassment.

“I must have lost my pouch as I was running this morning,” he finally said.

I figured as much. I turned to Lavon. “That will make for an interesting find, will it not? A two thousand year old battery from a Handycam.”

Lavon shook his head as he thought back to the odd discovery that had led him to his current situation.

“No one will be able to date it,” he finally said.

***

As the western sky faded to dusk, a servant brought in an oil lamp and placed it in the center of the table. After the man departed, I took the wine jar and filled five goblets.

After handing one to Sharon – the others could fend for themselves – I took the seat facing the door and held up my chip.

“Speaking of lost pieces of plastic, does everyone still have theirs?”

The others reached into their pouches and said yes. Bryson, too, pulled his out and laid it on the table, though this one looked a bit different. Instead of being composed of a single uniform wafer, like ours, the center of his glowed red.

“It’s a low power LED,” he explained. You all have earlier prototypes. Given the unknowns involved in this venture, we realized that it might become essential for me to have some warning that my return could be delayed, so that I could have at least a minimal opportunity to take evasive action.”

I couldn’t argue with that, though it hadn’t done us much good so far.

Bryson continued to stare at the chip. Finally, he just shook his head. “I just don’t know what

possibly

could be wrong?”

“Well,

something

is not right,” said Markowitz.

The others joined in and I let them vent for a few minutes. Finally, though, I held up my hand. We needed solutions, not arguments.

“The way I see it,” I said, “we need to work out hypotheses as to what the problem might be, though our key concern for the moment is how long we’ll have to stay in the good graces of the Roman army.”

Bryson held up his wine goblet. “You seem to have done a decent job of that so far. Obviously, we’re not prisoners.”

“No.”

“Then why do you think – ”

Lavon rose, walked over to a window and once again looked down. The drop was over one hundred feet.

“We’re not prisoners, but we can’t exactly leave,” he said. “I don’t think they know

what

to do with us. With all the crowds coming in for the Passover, they’re rather busy, so my guess is they’re going to keep us here until the festival is over and sort everything out then.”

“Keep us here, in this room?” asked Markowitz.

“Yes, as

guests

– unless something changes their mind.”

“Do you think they believe our story?” Sharon asked.

“It’s plausible,” Lavon replied. “Rome took control of Egypt around 30 BC, or about sixty years before Christ’s ministry. The army brought enormous quantities of loot back to the capital, and wealthy Romans went nuts over the stuff. Owning Egyptian artifacts became the ‘in’ thing for the high society of the time.”

“I saw Egyptian obelisks in modern Rome,” she said.

“That’s right,” replied Lavon. “There’s even one at the center of St. Peter’s Square. Medieval popes restored many of the ones that had fallen after the Empire crumbled.”

“OK, then,” I said. “‘Plausible’ should be good enough, at least for the moment.”

“Saving that soldier got us some Brownie points, too,” said Markowitz.

“Yes, but that’s also part of our problem,” replied Lavon. “Word of something so obviously useful …”

“They’ll want more,” I said.

“I’m certain of it. How many more of those things do you have?”

“Three.”

“I’d be prepared to hand them over, though the more difficult question will be where you got them in the first place. To the Romans, the Germans are uncultured barbarians, and anyone from lands beyond Germany is probably even worse.

“Let’s face it,” Lavon continued, “Two thousand years ago – or right about now, as strange as it is to say – our ancestors were crawling around the forests of northern Europe wrapped in animal skins. The Industrial Revolution is a long way off.”

“Mine weren’t,” said Markowitz.

I gave him an odd glance, but let his comment pass.

“Couldn’t we have picked up some technology along the way?” asked Bryson.

“Sure, but where? I had to tell Publius that we came to Judea around the eastern part of the Black Sea. The Romans already occupied the western side – modern Romania and Bulgaria – and I couldn’t run the risk of saying we had traveled though some place this guy might have actually seen in person.”

“Why is that a problem?”

“To the east you either have steppes, home to nomadic horsemen, or the Caucasus, the domain of wild mountain tribes. We’re unlikely to have picked up any advanced science from either group.”

“What about China?” asked Bergfeld. “They had advanced technology for the era, and the Silk Road went – ”

I had to interrupt. Complex webs of lies eventually spun out of control, a phenomenon that had allowed me to make a nice living over the past few years. The closer we stuck to the truth, the less risk we would run.

Bryson, though, was no longer paying attention. He stared down at his chip, which still glowed bright red.

“I think I’ve figured out what happened: Scott must have reprogrammed the machine. I configured the chips with an automated recall feature. We had to have that anyway for the first live animal tests, and Juliet insisted that she retain some way to retrieve me later on, even though we had proven that the technology operated precisely according to its design parameters.”

“OK, but how does that impact our situation now?” I asked.

“You were right in your suspicions earlier today, Mr. Culloden: there’s no way Juliet would have voluntarily permitted him to come back here. Since he undoubtedly knew that, he would have altered the recall feature to keep her from bringing him straight back to Boston as soon as he arrived in this world.”

“I would imagine he’d want to go back at some point,” said Lavon.

“True; but he would have wanted to stay through Sunday. The young man was quite a fan of Dawkins, especially his latest work.”

Several years earlier, Richard Dawkins, an English biologist, had written a book entitled

The God Delusion

. At last count, it had sold over a million copies.

“He would have seen this as a golden opportunity,” said Bryson.

“To do what?” said Sharon, “to show that we Christians are all fools?”

Bryson nodded. “I cautioned him that a true scientist must keep his mind open to the objective evidence, whichever way it falls, and not try to

demonstrate

anything, one way or the other.”

“That’s what all scientists are supposed to do, isn’t it?” asked Markowitz.