The Thing with Feathers (25 page)

Read The Thing with Feathers Online

Authors: Noah Strycker

Beccari—probably the first European naturalist ever to lay eyes on a bower in New Guinea—took it for a construction of one of the local tribes, though he had no idea what it was for. Ceremonial offering? Children’s plaything? The tiny hut was baffling. When he eventually caught the bowerbird at its “cabin,” Beccari became so awed by the structure that he spent several days observing and sketching it with crayons, noting in detail the various architectural features and decorations.

This isn’t the only time in history that someone has mistakenly attributed the work of animals to humans. There is the story of a classic art hoax in Sweden when, in 1964, amid the post–World War II explosion of abstract painting, a mischievous journalist persuaded a zookeeper to give oil paints to a four-year-old chimpanzee named Peter. After the ape learned to smear the colors onto canvas with a paintbrush, the journalist entered four of Peter’s best works in an art show at a museum in Göteborg, Sweden’s second-largest city, under the French alias Pierre Brassau. The paintings were displayed alongside those of other European artists without any indication of their true provenance, and art critics gave them nearly universal praise. One reviewer, who panned the rest of the show, wrote, “Pierre is an artist who performs with the delicacy of a ballet dancer.” (A dissenting critic aptly suggested that “only an ape could have done this.”) One of Peter’s paintings sold for $90 (about $700 today) to a collector. When Brassau’s true identity was revealed, the critics were even more impressed—and the chimp’s fame spread worldwide.

Art hoaxes—as well as the plethora of artistic paintings by orangutans, elephants, gorillas, and other animals that are being sold with full disclosure by their owners—highlight the difficulty of defining art strictly by appearance. If we can’t even tell whether a particular object has been made by a bird, a

chimpanzee, or a human, then who are we to judge what is art and what isn’t? It’s just too hard, and probably hypocritical, to limit art to people. Humans do not seem to have a lock on creativity.

The best definition of art may just be the simplest: Art is whatever an artist says it is. If someone creates in the spirit of artistry, then so it shall be considered by everybody else. However circular this logic may seem, there is often no way to know what went into a piece without guidance from its creator—which is why, in art gallery exhibits, viewers often spend as much time reading the tiny informational placards as appreciating the artwork on display. We want to know who made it, how they did it, and what it means. If beauty is in the eye of its beholder, then art, by definition, is in the intention of its maker.

Unfortunately, we don’t know what goes through a bowerbird’s mind while he builds and decorates his bower. Does the bird derive satisfaction beyond the occasional female stopping by? Does he think of himself as talented? If we could ask, would a bowerbird call his own bower art? Because we can’t ask, we’re not sure how we should respond to their curious structures.

We do know that bowerbirds are quite intelligent. If any birds were to channel the abstract thought necessary to make art, bowerbirds would be good candidates. They are most closely related to the corvid family, which includes crows, ravens, and jays—perhaps the smartest birds on the planet—with boldly curious personalities to match.

Many bowerbirds are excellent vocal mimics, traditionally a hallmark of intelligence. The MacGregor’s bowerbird, which inhabits mountainous parts of New Guinea, has been recorded imitating the sounds of waterfalls, pigs, and human speech.

Some species also use tools, appropriating sticks as brushes to paint the insides of their bowers with chewed-up plant goo.

They have larger brains than other similar-sized birds, and research has shown that the bowerbird species with the most complex bowers have the largest brains (and the males, who do all the building and decorating, have slightly larger brains than the females).

It does seem a stretch to suggest that bowerbirds consider themselves artists the way we do, given their overt and overwhelming motivation of seduction; the birds’ attention is probably directed more at passing females than creative immortality. So the art-by-its-maker definition would rule out bowerbirds. They probably don’t see art as some higher discipline. But until very recently, neither did we. Dictionary definitions of art have changed over time, and it’s only within the past four hundred years or so that art has begun to stand for something other than straightforward craftsmanship. Throughout most of history, people valued art because it was useful; artists were good at making things, and artwork was defined by its inherent quality. Even during the Renaissance, celebrated painters were often viewed more as skilled craftsmen than intellectuals.

The first copyright laws weren’t enacted until the 1700s, and before that, few artists had notions of creative ownership. In earlier times, copying artwork was good exercise. Those with the skill to do it were regarded with the respect of an original artist, because art and craft were the same. But that has changed. Today, forgers are thrown in jail, and a Monet may sell for tens of millions, while a forged one is comparatively worthless—even if the most knowledgeable experts can hardly tell the difference. The definitions of art and skill have separated so that we now value reputation as much as talent, concept as much as execution.

Bowerbirds are yesterday’s craftsmen, spending their lives honing skill and technique to achieve the perfect bower. A few hundred years ago, that would have satisfied every definition of human art, but today it’s not good enough; because the birds don’t sign their names or explore themes, they fail to qualify as artists. Honestly, I’m not sure whether this distinction reflects better on us or on them.

Sometimes I feel a little sorry for bowerbirds. They have become so devoted to making a good impression that they don’t have anything left for the females they want to impress. Male bowerbirds, whether struggling artists or crafty seducers, are lifetime bachelors, so absorbed in their work that they will never raise their own children. The perfect bower leaves no time for anything else.

fairy helpers

WHEN COOPERATION IS JUST A GAME

W

henever the temperature climbed above 110 degrees Fahrenheit, which happens often in northwest Australia, I would retreat into the walk-in refrigerator at Mornington Sanctuary, pull the heavy door shut, turn out the lights, and think about purple-crowned fairy-wrens. Never mind how the dainty birds survive in an environment so extreme that even Sir Sidney Kidman—Australia’s famous cattleman, who, in the early 1900s, turned five shillings and a one-eyed horse into ownership of 3 percent of the entire continent—couldn’t handle the area. (He cited “natives spearing the cattle” and “the precipitous state of the country” when he abandoned Mornington; no fridge back then.) I was rather more impressed with the fairy-wrens’ social habits. In the loneliest corner of the scorched outback, where groceries are delivered by bush plane and solitude lies like a hot blanket, miniature soap operas play out every day. You just have to know where to look.

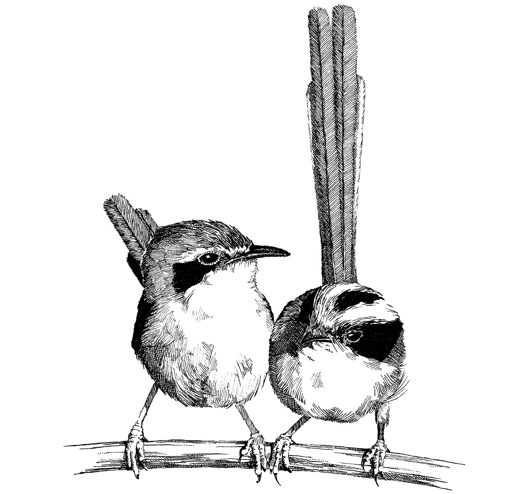

Fairy-wrens, with the body and bounce of a Ping-Pong ball fixed with a pencil-sized tail, make up for their diminutive stature with blatantly colorful attire. There are fourteen species of fairy-wrens overall, nine of them in Australia, all of them visually sparkling. Males of the purple-crowned variety, which is endemic to the arid northern interior, sport a candy violet hairdo, black cheeks, and a long, expressive tail that shimmers as blue as the sky. Females are more demurely patterned with slaty crowns and a reddish cheek patch broken by a white eye ring. But it’s their cooperative personality that most fascinates fairy-wren admirers.

A hundred yards from my icebox retreat, one particular

female purple-crowned fairy-wren could reliably be found industriously tending her brood. As fairy-wrens go, she was relatively hardworking. Along with a studly mate, she’d already raised two healthy nestlings who had left the nest a couple months earlier. Now she was in charge of a second nest, a tightly woven ball of grass and leaves with an entrance hole on the side, protected by a stalk of spiky pandanus shrubbery along a small creek. But her earlier young, now grown to adult size, hadn’t yet left the territory. Instead of dispersing, as most birds do after fledging from the nest, they hung around and helped their parents raise the next brood, bringing extra food to their younger brothers and sisters. That was where things got interesting.

I knew this because I’d spent countless hours—days, weeks, months—carefully watching them as part of a long-term study of the birds’ habits. I recognized by sight every individual fairy-wren along a ten-kilometer stretch of creek, which amounted to one sprawling family of a hundred siblings, uncles, cousins, grandparents, and occasional newcomers, all packed into forty well-defined territories. It was like a suburban street, forty houses long, in a neighborhood where everyone knew one another.

On this particular street, neighbors sometimes pop in to take care of one another’s kids, an unusual habit among birds. Only a very few birds, somewhere between 3 and 8 percent of the world’s total species—including acorn woodpeckers, Florida scrub jays, and groove-billed anis, among others—will ever voluntarily tend another’s young. This kind of cooperative nesting presents an evolutionary enigma at first glance. Why would any creature, generally assumed to place its own interests first in order to survive and reproduce, willingly help another, at cost to itself, with no obvious benefit?

The longer I watched fairy-wrens, the more I became fascinated by this question. I read up on cooperative behaviors in all kinds of animals and discovered that wild creatures don’t always behave as selfishly as you might think. Vampire bats form buddy systems, regurgitating blood for each other when a pal goes a night without a meal. Dolphins push sick or injured individuals—occasionally even of other species, such as seals and humans—to the surface to breathe. Lemurs care for unrelated infants. The list goes on and on; it seems that people aren’t the only ones who help one another from time to time.

Even within the realm of birds there are many examples of cooperative behavior. When a bird sees a predator, it will often give an alarm call that alerts others in the area—sometimes of different species—to the danger, even though doing so attracts attention and presumably increases the whistle-blower’s chance of being eaten. Some birds that feed in flocks, such as quail, habitually post sentries to stand watch while the others eat their fill. Why take the extra risk? If every bird was completely selfish, none should be willing to protect others while placing itself in harm’s way.

The literature on human altruism—good deeds performed at cost to oneself with no expectation of a returned benefit—is just as interesting. In terms of playing nice, we may not be much different from other animals, and we may have less control over our actions than we like to think. It’s possible that cooperation itself can be explained by mathematical theories, with wide-ranging implications for criminals, cheating, the Cold War, the Golden Rule, forgiveness, cancer research—and, yes, fairy-wrens.

Cooperative nesting is the ultimate example of altruistic behavior, as it so clearly helps another individual affect the next generation. By tending one another’s nests, fairy-wrens seem to

violate a basic principle of Darwinian evolution lately championed by the author Richard Dawkins—that the need to pass on your genes supersedes all else. If reproduction is the primary goal, then it seems illogical to help raise someone else’s kids while delaying your own.

Geography gives a basic hint to the puzzle. Of the few birds that do nest cooperatively, many of them are concentrated in Australia and Africa, and a lot of those birds, including fairy-wrens, live in scrubby habitats or grassy savannas. An unpredictable environment, such as a savanna that experiences sudden droughts and rainy periods—or, say, a stock market investment business—favors diversified team efforts. On a finer scale, places where prime territory is limited may foster a system in which young birds must stay with their parents until a vacancy opens up elsewhere, effectively paying rent until they can strike out on their own.

But geography can’t entirely clarify the cooperative behaviors of fairy-wrens, which sometimes have nest helpers and sometimes don’t. Scientists are interested in the evolution of cooperation because it seems counterintuitive; efforts to explain selfless behaviors usually involve some ultimate benefit with the idea that all behaviors, in the end, are actually selfish. The question becomes whether pure altruism even exists or whether all “nice” actions calculably benefit the do-gooder. Let’s be honest: When humans are nice to one another, it’s often for an ultimately selfish reason. Fairy-wrens might not be much different.

—

THE MOST OBVIOUS EXPLANATION

for cooperative nesting is that helpers are usually relatives. In terms of furthering your own genetic legacy, a brother is the same as a son: Both share 50

percent of your genes. Assuming that they are closely related to the true parents, fairy-wren helpers are reaping the genetic benefits of raising children without bothering to have kids of their own, sort of like an older brother babysitting his younger sibling while their parents go out to the movies. It’s a job, but it does end up protecting at least some of the helpers’ own genes.