The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy (18 page)

Read The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy Online

Authors: Irvin D. Yalom,Molyn Leszcz

Tags: #Psychology, #General, #Psychotherapy, #Group

This chapter underscores the point that some factors are not always independent mechanisms of change but instead create the conditions for change. For example, as I mentioned in chapter 1, instillation of hope may serve largely to prevent early discouragement and to keep members in the group until other, more potent forces for change come into play. Or consider cohesiveness: for some members, the sheer experience of being an accepted, valued member of a group may in itself be the major mechanism of change. Yet for other members, cohesiveness is important because it provides the conditions, the safety and support, that allow them to express emotion, request feedback, and experiment with new interpersonal behavior.

Our efforts to evaluate and integrate the therapeutic factors will always remain, to some extent, conjectural. Over the past twenty-five years there has been a groundswell of research on the therapeutic factors: recent reviews have cited hundreds of studies.

1

Yet little definitive research has been conducted on the comparative value of the therapeutic factors and their interrelation; indeed, we may never attain a high degree of certainty as to these comparative values. We have summaries at the end of sections for those readers less interested in research detail.

I do not speak from a position of investigative nihilism but instead argue that the nature of our data on therapeutic factors is so highly subjective that it largely resists the application of scientific methodology. The precision of our instrumentation and statistical analysis will always be limited by the imprecision of our primary data—the clients’ assessment of what was most helpful about their group therapy experience. We may improve our data collection by asking our clients these questions at repeated intervals or by having independent raters evaluate the therapeutic factors at work,

2

but we are still left trying to quantify and categorize subjective dimensions that do not fit easily into an objective and categorical system.†

3

We must also recognize limits in our ability to infer objective therapeutic cause and effect accurately from rater observation or client reflection, both of which are inherently subjective. This point is best appreciated by those therapists and researchers who themselves have had a personal therapy experience. They need only pose themselves the task of evaluating and rating the therapeutic factors in their own therapy to realize that precise judgment can never be attained. Consider the following not atypical clinical illustration, which demonstrates the difficulty of determining which factor is most therapeutic within a treatment experience.

• A new member, Barbara, a thirty-six-year-old chronically depressed single woman, sobbed as she told the group that she had been laid off. Although her job paid poorly and she disliked the work, she viewed the layoff as evidence that she was unacceptable and doomed to a miserable, unhappy life. Other group members offered support and reassurance but with minimal apparent impact. Another member, Gail, who was fifty years old and herself no stranger to depression, urged Barbara to avoid a negative cascade of depressive thoughts and self-derogation and added that it was only after a year of hard work in the group that she was able to attain a stable mood and to view negative events as disappointments rather than damning personal indictments.

Barbara nodded and then told the group that she had desperately needed to talk and arrived early for the meeting, saw no one else and assumed not only that the group had been canceled but also that the leader had uncaringly failed to notify her. She was angrily contemplating leaving, when the group members arrived. As she talked, she smiled knowingly, acknowledging the depressive assumptions she continually makes and her propensity to act upon them.

After a short reflection, she recalled a memory of her childhood—of her anxious mother, and her family’s motto, “Disaster is always around the corner.” At age eight she had a diagnostic workup for tuberculosis because of a positive skin test. Her mother had said, “Don’t worry—I will visit you at the sanitarium.” The diagnostic workup was negative, but her mother’s echoing words still filled her with dread. Barbara then added—“I can’t tell you what it’s like for me today to receive this kind feedback and reassurance instead.”

We can see in this illustration the presence of the several therapeutic factors—universality, instillation of hope, self-understanding, imparting information, family reenactment, interpersonal learning, and catharsis. Which therapeutic factor is primary? How can we determine that with any certainty?

Some attempts have been made to use subjectively evaluated therapeutic factors as independent variables in outcome studies. Yet enormous difficulties are encountered in such research. The methodological problems are formidable: as a general rule, the accuracy with which variables can be measured is directly proportional to their triviality. A comprehensive review of such empirical studies produced only a handful of studies that had an acceptable research design, and these studies have limited clinical relevance.

4

For example, four studies attempted to quantify and evaluate insight by comparing insight groups with other approaches, such as assertiveness training groups or interactional here-and-now groups (as though such interactional groups offered no insight).

5

The researchers measured insight by counting the number of a therapist’s insight-providing comments or by observers’ ratings of a leader’s insight orientation. Such a design fails to take into account the crucial aspects of the experience of insight: for example, how accurate was the insight? How well timed? Was the client in a state of readiness to accept it? What was the nature of the client’s relationship with the therapist? (If adversarial, the client is apt to reject any interpretation; if dependent, the client may ingest all interpretations without discrimination.) Insight is a deeply subjective experience that

cannot be rated by objective measures

(one accurate, well-timed interpretation is worth a score of interpretations that fail to hit home). Perhaps it is for these reasons that no new research on insight in group therapy and outcome has been reported in the past decade. In virtually every form of psychotherapy the therapist must appreciate the full context of the therapy to understand the nature of effective therapeutic interventions.

6

As a result, I fear that empirical psychotherapy research will never provide the certainty we crave, and we must learn to live effectively with uncertainty. We must listen to what clients tell us and consider the best available evidence from research and intelligent clinical observation. Ultimately we must evolve a reasoned therapy that offers the great flexibility needed to cope with the infinite range of human problems.

COMPARATIVE VALUE OF THE THERAPEUTIC FACTORS: THE CLIENT’S VIEW

How do group members evaluate the various therapeutic factors? Which factors do

they

regard as most salient to their improvement in therapy? In the first two editions of this book, it was possible to review in a leisurely fashion the small body of research bearing on this question: I discussed the two existing studies that explicitly explored the client’s subjective appraisal of the therapeutic factors, and then proceeded to describe in detail the results of my first therapeutic factor research project.

7

For that undertaking, my colleagues and I administered to twenty successful group therapy participants a therapeutic factor questionnaire designed to compare the importance of the eleven therapeutic factors I identified in chapter 1.

Things have changed since then. In the past four decades, a deluge of studies have researched the client’s view of the therapeutic factors (several of these studies have also obtained therapists’ ratings of therapeutic factors). Recent research demonstrates that a focus on therapeutic factors is a very useful way for therapists to shape their group therapeutic strategies to match their clients’ goals.

8

This burst of research provides rich data and enables us to draw conclusions with far more conviction about therapeutic factors. For one thing, it is clear that the differential value of the therapeutic factors is vastly influenced by the type of group, the stage of the therapy, and the intellectual level of the client. Thus, the overall task of reviewing and synthesizing the literature is far more difficult.

However, since most of the researchers use some modification of the therapeutic factors and the research instrument I described in my 1970 research,

9

I will describe that research in detail and then incorporate into my discussion the findings from more recent research on therapeutic factors.

10

My colleagues and I studied the therapeutic factors in twenty successful long-term group therapy clients.

11

We asked twenty group therapists to select their most successful client. These therapists led groups of middle-class outpatients who had neurotic or characterological problems. The subjects had been in therapy eight to twenty-two months (the mean duration was sixteen months) and had recently terminated or were about to terminate group therapy.

12

All subjects completed a therapeutic factor Q-sort and were interviewed by the investigators.

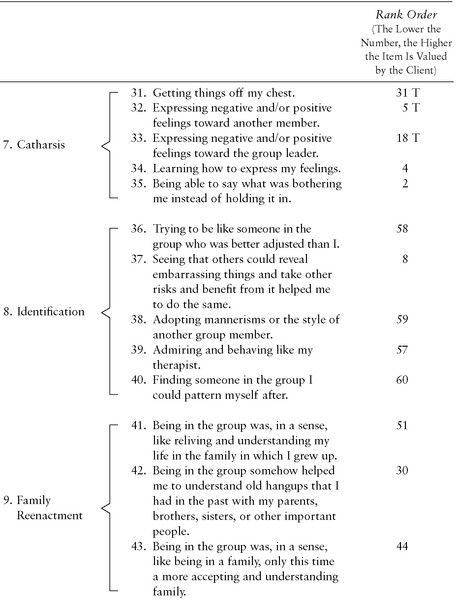

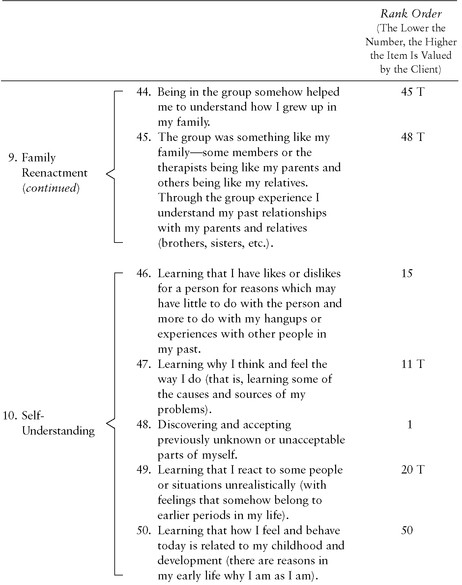

Twelve categories of therapeutic factors were constructed from the sources outlined throughout this book,

13

f

and five items describing each category were written, making a total of sixty items (see

table 4.1

). Each item was typed on a 3 × 5 card; the client was given the stack of randomly arranged cards and asked to place a specified number of cards into seven piles labeled as follows:

Most helpful to me in the group (2 cards)

Extremely helpful (6 cards)

Very helpful (12 cards)

Helpful (20 cards)

Barely helpful (12 cards)

Less helpful (6 cards)

Least helpful to me in the group (2 cards)

14

TABLE 4.1

Therapeutic Factors: Categories and Rankings of the Sixty Individual Items