The Testimonium (11 page)

“Not a lot to say,” she said. “I was born on a small farm near —” But before she could get any further, the trailer doors opened and Father MacDonald came in, followed by Dr. Rossini. “Good morning, gentlemen,” said Isabella.

“

Bon journo

, Isabella.” said Rossini. “The coffee smells wonderful! So what is our first order of business today?” he asked as he poured a cup and gave it a small dose of crème de menthe.

“Last night’s discovery first,” she said. “Father MacDonald, I want you and Josh to see if we can remove the items from the drawer without damaging them.”

“I don’t think I can do it without damaging meself until I have some coffee, lass,” said the Scottish priest. Josh noticed that MacDonald’s accent was always stronger when he was clowning around, while it became almost unnoticeable when he was serious. The Scottish priest poured himself a large mug of coffee; meanwhile, Rossini went over to a cabinet and opened it, pulling out a large covered tray that was full of pastries when he took the lid off of it.

“I told Signora Bustamante to send up a tray of breakfast items with our dinner last night,” he said. “These are cold but still quite fresh—she baked them yesterday evening along with our meal.”

The scientists dug in with gusto, snagging cinnamon rolls and strudels with abandon. Josh allowed himself two of the rolls, and then paused with his mouth full.

“We need to take some of these to Dr. Apriceno,” he said. “Or at least tell her they are here. She’s already working with nothing but a cup of coffee in her belly.” He grabbed a large butter pecan Danish and laid it on a napkin, walking out of the trailer toward the alcove. The plastic shield that had replaced the makeshift tarp covered the entrance, but had a vertical zippered opening for the team to come and go. He could hear the high-pitched whirr of the vacuum going. The archeobotanist was still working near the entrance to the chamber, busily sucking up centuries of dust while being very careful not to vacuum up anything that wasn’t stone dust. Josh called her name twice and finally tapped her shoulder. She started, then stood upright and shut off the small but powerful appliance. “I thought you might like some breakfast,” Josh said.

“

Grazi

,” she replied. “You are very considerate.” She took a large bite of the Danish and gave a small groan of satisfaction. The town’s restaurant was well known for its food, and the breakfast was outstanding.

“So have you found anything, now that the dust is being removed?” Josh asked.

“I’ve only uncovered the nearest part of the alcove, where the table and lamp were located,” she said. “There appears to be some graffiti on the wall next to the desk.” Joshua peeked in. Uncovered by the removal of centuries of dust, a crude drawing was revealed in the halogen light, about four feet off the ground—roughly head level for someone seated at the desk, he realized. The drawing had been made by a blade of some sort scratching into the masonry of the wall. There was a crude serpent wrapped around some buildings and people, with an evil grin on its fanged, humanoid face. Beneath it the words “

Gaius Caligula serpens Roma

” had been hacked in large crude Latin letters.

“Looks like Suetonius did get something right,” said Josh. “He said in his chronicles that old Tiberius told his friends that he was ‘raising up a viper for Rome’ in the form of Caligula. Let me go tell Dr. Sforza about this—she will want to get some pictures.”

After the new find in the chamber was photographed and recorded, the four team members met back in the lab, while Apriceno got back to her work. Father MacDonald carefully studied the objects inside the small drawer under the table, and then called Josh over for a quick consultation. After conferring for a few moments, they turned to the others.

“It appears the papyrus inside the drawer has not adhered to the wood of the drawer’s bottom at all,” said MacDonald. “Probably because the inside of the drawer was not lacquered, like the top of the desk, and also because there was not several centimeters of dust on top of the papyrus, pressing it into the wood. I think we can remove the papyrus and the leather purse on top of it all at the same time. The leather on the drawstring bag is completely stiffened, of course, so we will first X-ray it to see what is inside, and then begin rehydrating the leather so that we can open the bag without destroying it.”

“How do you propose to remove it from the drawer?” asked Isabella.

“Simple,” said Josh. He held up a small, thin, rigid square of plastic. “We trimmed this from an extra plexiglass container lid. It is very thin, but still quite rigid. We cut it to the exact width of the papyrus sheets inside the drawer, and made it a little longer than the drawer is deep. We are going to carefully slide it underneath the bottommost piece of papyrus all the way to the back of the drawer, then lift the entire stack onto this tray and carry it straight to the X-ray machine. We’ll take a quick picture or two of the bag’s contents, and then slide the tray into the rehydration tank. In twenty-four to forty-eight hours, the leather should be supple enough for us to tease the drawstrings open a bit and remove the contents. We should also be able to separate the purse from the papyrus sheets and see if we have anything other than a stack of blank writing paper here.”

“Excellent description, Josh,” said Father MacDonald. “You have very steady hands, so I will nominate you to do the actual removal when you are ready.”

“All right, Professor,” said Parker. “You hold the tray. The goal is to leave the drawer’s contents unsupported for the least amount of time possible. Bring it over here to my right—that’s good.”

Rossini and Sforza leaned in to watch. This was the most delicate part of any archeological excavation—removing a fragile artifact from its original context. Done properly, it made a relic available for closer study and examination with no impact on its stability or condition. But if botched, the process could destroy a priceless piece of history in the blink of an eye. Both were holding their breath as Josh approached the tiny drawer that had remained hidden for two millennia.

He carefully laid the plexiglass sheet flat on the bottom of the drawer, then used a flat, spatula-like blade to slowly lift one corner of the bottommost sheet of papyrus. He slowly eased the plexiglass underneath that edge, then carefully moved the blade across, lifting the ancient writing paper one inch at a time until the plexiglass had slid under its entire width. Then he slowly moved the spatula back to the center, gently lifting the entire stack a fraction of an inch and sliding the sheet in a bit further. Back and forth, across the sheet of papyrus he went, slowly sliding the plastic further underneath it until it reached more than two inches underneath the stack. “That’s as far as this tool can reach underneath without potentially tearing the edge of the papyrus,” he said. “Now I will use the sheet itself to lever the stack upward and slide back.” He set the spatula-like instrument aside, then carefully took the sheet and pressed down on the far end. The stack of papyrus, and the purse on top of it, slowly lifted up without resistance. He slid the sheet back an inch further, and then repeated the process until finally, the plexiglass bumped against the back of the drawer. The four archeologists breathed a collective sigh of relief.

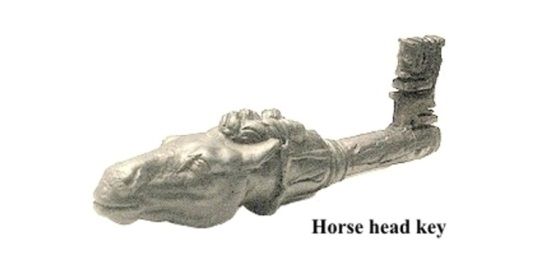

“Now then,” he said. “Stand by with that tray, Father MacDonald!” He took a deep breath and grabbed the plexiglass by each edge, slowly lifting and pulling it up and back. The stack of papyrus sheets and the leather drawstring bag on top of it emerged into the light with a tiny puff of dust and a few ancient cobwebs trailing behind them. The golden horse’s head glittered under the lab’s fluorescent lights, peeking out of the mouth of the purse as it had for so many centuries. Josh lifted it and looked at the jeweled eyes. “Time to tell us your story, little guy!” he said, and then placed the papyrus sheets onto the tray that Father MacDonald was holding. The priest/archeologist quickly placed the tray on a small rolling cart and wheeled it across the lab to the X-ray table. The XFA—or the Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Analyzer, to give it its proper name—was a small tabletop unit that put forth minimal radiation and was used in archeological field work all over the world. The images it produced were not nearly as refined as a large, laboratory-based X-Ray Analyzer, nor as clear as a CT-scan or MRI, but it was a very handy device for taking a quick look inside sealed containers, ancient wrappings, and mummified remains.

Once the tray was set in place, the group came to take a closer look, seeing the entire surface of the ancient papyrus for the first time. It was completely blank, except for a small ink mark at the top corner of the top sheet. There was a large, brown stain surrounding the ancient drawstring bag, darkest directly under it and fading like a corona until it ended, about an inch away from point of contact where the bag rested on the papyrus. There was nothing else resting on the papyrus other than the ancient purse. Moving deftly, MacDonald set the parameters on the XFA and drew the lead-lined curtain around the tabletop. “Stand back, my colleagues, you know the protocol,” he said as he took the remote in hand. When everyone had scooted back the prescribed ten feet, he himself stepped back and pushed the buttons on the remote, adjusting the angle and taking several shots of the ancient coin purse. Then he stepped across the room to a monitor and they all waited as the images slowly downloaded onto the desktop file. Once the download was complete, he double-clicked on the file and pulled up the first image. Several objects showed on the first X-ray. A group of small metallic discs—most likely coins—were clumped together near the bottom of the purse. A narrow, pointed object lay on top of them, its wider end difficult to see from the angle of the shot.

But the small item with the horse’s head on one end was at the opposite end of the small bag, apparently having been shoved in at the last possible moment. There was nothing overlapping or obscuring the unmistakable shape. Josh chuckled. “Well, that’s one mystery solved!” he said.

“A key!” exclaimed Isabella.

“I just wonder what it opens?” asked Dr. Rossini.

At this point, most excellent Tiberius, I felt that I could not proceed any further without at least trying to find out what this Galilean holy man had to say for himself. My Aramaic is not the best, so I sent one of my Centurions into the crowd to find an interpreter. He returned a few moments later with a terrified-looking youth of about twenty years of age, whom he described as one of the Galilean’s disciples. I found myself admiring his courage, following a screaming mob that was howling for his master’s blood! The young fellow did not speak Latin very well, but his Greek was quite passable. Although the mob outside and their religious leaders had voiced many charges against the bloodied figure before me, I asked him about the only one that really mattered to me as a Roman magistrate. “Are you the King of the Jews?” I demanded, nodding at the youth to translate.

My interpreter proved unnecessary. Jesus looked at me with a deep and curious gaze that I found quite unnerving, then spoke in clear, excellent Latin without a trace of an accent. “Do you say this of your own accord?” he asked. “Or did someone else tell you this about me?”

“Am I a Jew?” I asked, more harshly than I intended. His intense stare was throwing me off balance. “Your own people—your own priests—have delivered you up to me as an evildoer. What do you say for yourself?”

He was silent for a long moment, his lips moving as if he were speaking to someone I could not see. Finally, his eyes met mine again, and he spoke with incredible force and clarity. “My kingdom,” he said, “is not of this world!”

“That’s a good question,” Duncan MacDonald said as he studied the white-on-black image on the screen. “A logical guess would be that it fits the reliquary that we have yet to uncover. We may get a chance to find out fairly soon, once Simone is done clearing the dust from the chamber. In the meantime, we will have to content ourselves with beginning the process that will let us remove the contents from this leather purse for a closer examination.”

He pulled the lead-lined curtains back, and took the tray with the purse and papyrus sheets on it across the lab to a small tank that looked for all the world like a terrarium. He set the tray inside and pulled the plexiglass door down, sealing the gasket along the bottom so that the tank was airtight. Then he set a series of controls at the top and punched in some commands. “The humidity is set at seventy-five percent,” he said. “A bit high for a papyrus document, but just about right for leather. There is enough antiseptic in the tank’s atmosphere to prevent the growth of any mold whose spores may be embedded in the leather or the papyrus. It should take about twenty-four to forty-eight hours for the material to be rehydrated enough to flex without crumbling. Unless Simone uncovers more small items that can be removed, our next object of study will be the lamp from the niche above the door.”

Isabella spoke up. “Then it appears we may be in for a lull of about twenty-four hours or more,” she said. “Dr. Apriceno will not be done clearing the dust from the chamber till this evening, and then we will need to take a careful inventory of the chamber and any additional items uncovered by the removal of all the dust and debris. You and Dr. Parker are more than capable of doing that without me. I want to take Dr. Rossini back to Naples and confer with the Antiquities Bureau’s Director and Dr. Guioccini. I also want to get some security on-site, so that you can take a break from the tents this evening and spend the night in more comfortable quarters. We will need one archeologist to stay on-site at all times, of course, but there is simply no need for all five of us to be up here twenty-four hours a day.”