The Taste of Conquest (4 page)

Read The Taste of Conquest Online

Authors: Michael Krondl

In Europe, things were different. With the collapse of Rome, the orderly territories north of the Alps were ravaged. Wheat fields were bludgeoned into wastelands, and vineyards were trampled into dust. Trade was throttled. Great cities shriveled to hamlets. Ordinary folk resorted to scavenging for roots and nuts, while the warrior class tore at great haunches of roasted beasts, swilling beer all the while. Or that, at least, is our image of the Dark Ages. Undoubtedly, there were pockets of polished civilization amid the roughened landscape, especially in the monasteries, where fragments of a Roman lifestyle remained. Italy, in particular, retained active ties to both the current “Roman” empire in Byzantium as well as the memory of the old stamping grounds of the Caesars. All the same, whatever else you might say about the invasions of the Germanic and Slavic tribes that swept across the continent in those years, their arrival was hardly conducive to the culinary arts.

In the meantime, as Europe spiraled down into a recurring cycle of war, hunger, and pestilence, the Middle East flourished under a

Pax Arabica.

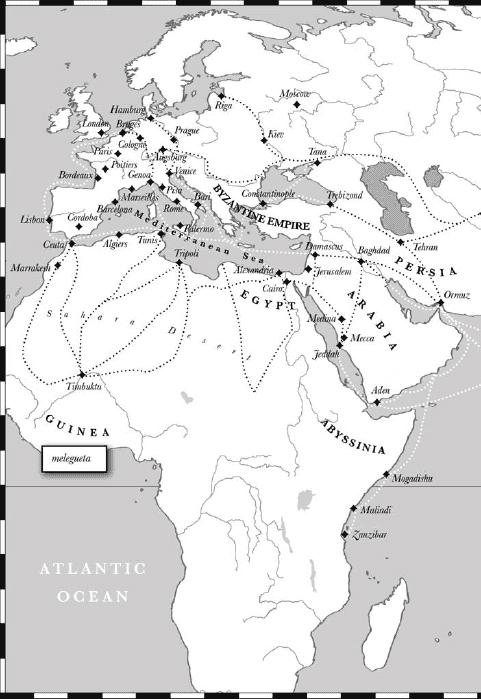

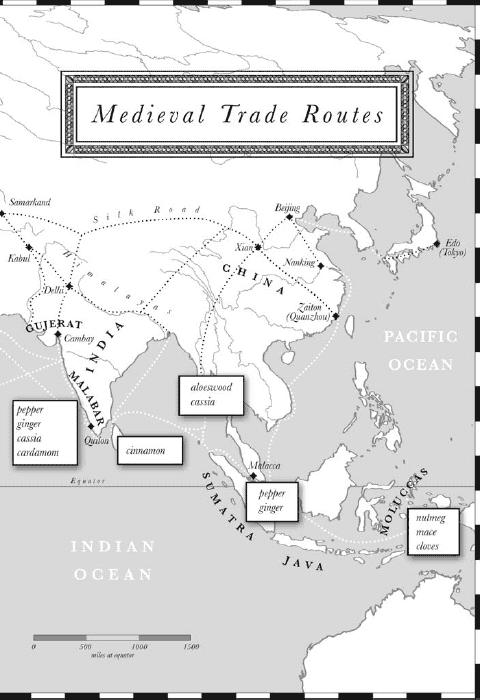

In Baghdad, the imperial capital, Persians, Arabs, and Greeks sat down at the same table to argue about medicine, science, the arts, and, naturally, what should be served for dinner. Arab merchants sent their agents to China, India, and Indonesia to shop for silks and jewels, but most especially for the spices that were the essential ornament to any sophisticated cuisine. Incidentally, it was those same spice traders who brought Islam to Indonesia and Malaysia. Meanwhile, in the West, Muslim armies had overwhelmed the Iberian Peninsula and penetrated deep into France. They took Sicily and all but a fragment of the Byzantine Middle East. In Jerusalem, mosques towered over Christian remains. For a time, the cries of muezzins calling the faithful to prayer could be heard from the dusty plains of Castile to Java’s sultry shores.

Quite reasonably, Christian Europe felt under siege, and its response came in a series of assaults on the Middle East between 1096 and 1291 that we call the Crusades. Yet the short-lived military success of the Crusaders in the Holy Land (they held Jerusalem for just eighty-eight years) pales in comparison to the ideological, cultural, and economic aftershocks that followed those first Catholic jihads.

Cultures typically gain their identity not only from what unifies them but, more important, from what sets them apart from their neighbors and foes. Today, for example, Europeans are united as much by the way they grouse about Americans as they are by the euro. In much the same way, the early medieval idea of Christendom—given the enormous political and economic differences within Europe—could not have been possible without the outside threat. On a more everyday level, the Crusades also changed tastes and fashions. The Norman knight who returned to his drafty St. Albans manor brought back a craving for the food he had tasted in sunny Palestine, much like the sunburned Manchester native does today when he returns from his Turkish holiday. In the Dark Ages, spices had all but disappeared from everyday cooking. With the Crusaders’ return, Europeans (of a certain class) would enjoy well-spiced food for the next six hundred years.

H

ARBORS OF

D

ESIRE

Over the centuries, people across the globe made piles of money from the European desire for pepper, cinnamon, and cloves. Merchants from Malacca to Marseilles built fabulous fortunes in the spice business. Monarchs in Cairo and Calicut financed their armies from their cut of the pepper trade. London, Antwerp, Genoa, Constantinople, Mecca, Jakarta, and even Quanzhou could attribute at least some of their wealth to the passage of the spice-scented ships. But nowhere were the Asian condiments the lifeblood of prosperity as in the great entrepôts of Venice, Lisbon, and Amsterdam. Each took her turn as one of the world’s great cities, ruling over an empire of spice. Venice prospered longest, until Vasco da Gama’s arrival in India rechanneled the flow of Asian seasoning. Then Lisbon had her hundred years of wealth and glory. Finally, Amsterdam seized the perfumed prize and ruthlessly controlled the spice trade in the century historians call the city’s golden age.

There are probably as many similarities among the three cities as there are differences. All of them ran (or at least dominated) small, underresourced countries, and so they didn’t have much choice but to go abroad to make good. Kings and emperors sitting on fat, tax-stuffed purses never had the same kind of appetite for the risky spice business. The great harbors were renowned for their sailors and shipbuilders (and, not coincidentally, their prostitutes). Nevertheless, they prospered in different times and in different ways. Venice was, in some ways, like a medieval Singapore, a merchant republic where business was the state ideology and the government’s main job was to keep the wheels of commerce primed and tuned. Pepper was the lubricant of trade. Lisbon, on the other hand, lived and breathed on the whim of the king, who had one eye on the spice trade even as the other looked for heavenly salvation. In the fifteenth century, Portugal had the good fortune to have a run of enlightened, even inspired monarchs who figured out a way to cut out the Arab middlemen by sailing right around Africa. Whether this pleased God is an open question, but it certainly gratified the pocketbook. The Dutch were much more down-to-earth. In Amsterdam, they handed the spice trade over to a corporation, which turned out to be a much more efficient and ruthless way to run a business than Lisbon’s feudal approach. Decisions made at the headquarters of the Dutch East India Company would transform people’s lives halfway across the globe. By the time the Hollanders were done, the world was a very different place from the one Mandeville wrote about in his

Travels.

In the meantime, the role of spices in European culture gradually shifted, from the talismans of the mysterious East carried on Venetian galleys, to exotic treasure packed in enormous carracks emblazoned with the Crusaders’ cross, and finally to a profitable but rather mundane commodity poured like coal into the holds of Dutch East Indiamen. All this as Europe was transformed from a continent joined (if intermittently) in its battle against Islam, united in its religion, and with an educated class conversant in the same language to a battleground of nation-states, divided by creed and vernacular. People still used plenty of pepper and ginger in post-Reformation Europe, but that’s mostly because they had become relatively cheap. The trendsetters had grown tired of spices, though, and the cuisine favored by generations of Medici, Bourbons, Hapsburgs, and Tudors was about to fundamentally change.

It was just around the time when the road to European world domination opened for business that Europeans’ tastes began to come home. Crusades and pilgrimages went out of fashion. And the orgy ended. Certainly not overnight and not everywhere, but in the fashion centers of Madrid and Versailles, spices no longer made the man. The vogue that had built Venice from a ramshackle fishing village on stilts into Europe’s greatest metropolis, the transient tastes of a few cognoscenti that had transformed Lisbon from a remote outcrop at the edge of Christendom into the splendid capital of a world-spanning empire, the culinary habits of a minute fragment of this small continent’s population that had lifted Amsterdam out of its surrounding bog and briefly made teeny Holland one of the great powers of the world—all this was over. Fashion had moved on.

A N

EW

W

ORLD

The voyages in search of the spiceries, whether successful like da Gama’s or misdirected like Columbus’s, had effects both profound and mundane. We all know of the disastrous fallout for Native Americans once Europeans arrived and the subsequent horrors of the transatlantic slave trade. Perhaps less well known is the genocide perpetrated by the Dutch East India Company in the nutmeg isles of Indonesia. Or the slave trade that flourished in the Indian Ocean to provide the Portuguese with sailors for their spice ships and to supply workers for Dutch nutmeg plantations. The Afrikaner presence in South Africa, the Boer War, and even the subsequent apartheid regime would never have existed if the Dutch hadn’t sent colonists to the Cape of Good Hope to supply their pepper fleets. Other consequences of the spice trade were more narrowly economic. The European appetite for Oriental luxuries meant that money kept flowing ever eastward. Armadas of silver sailed from Mexico and Peru to Europe but then, just as assuredly, kept going all the way to Asia to pay for the pepper that was sent back home. Asians wanted silver pieces of eight for their black gold. But the pepper ships weighed down with silver brought another kind of cargo on their outbound voyage. Franciscans and Jesuits came in the lee of the spice trade, and although their proselytization efforts could never keep up with the Muslim spice traders, at least Christianity was added to Asia’s assortment of religions. A cargo of perhaps even greater consequence was the foods brought along with the priests and the doubloons. New World crops such as corn, papayas, beans, squashes, tomatoes, and chilies were all transported in Portuguese ships bound for Africa, India, and the Spice Islands. Not that all the aftershocks of the spice trade were of seismic proportions. Everyday fashions were influenced by contacts with the East. The Portuguese penchant for blue and white tiles, for example, came about when they tried to imitate the Ming porcelain brought back with the pepper, and in Amsterdam, Indian fabric embroidered in the Mogul style was all the rage in its day.

We have been taught that history moves on great wheels, on world wars, on Napoleonic egos, on the revolutions of the masses, on vast economic upheavals and technological change. Yet small things, seemingly trivial details of everyday existence, can lead to convulsions in the world order. In trying to find a modern commodity that has the same transformative role played by spices in the expansion of Europe, historians have tried to make the analogy with today’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil. But that comparison is deeply flawed, for petroleum is absolutely critical to the day-to-day functioning of virtually every aspect of modern existence. Great oceans of petroleum are sent around the world every day. By contrast, in the early fifteen hundreds, almost all of Europe’s pepper arrived in a yearly armada of a half dozen Portuguese ships. It’s easy enough to understand why nations would go to war to safeguard oil, the lifeblood of their economy, but to risk life and limb for a food additive of virtually no nutritional content that only a tiny fraction of the population could even afford? Spices have about as much utility as an Hermès scarf. Yet it is precisely this inessentiality that makes them a useful lens for examining the human relationship to food. Once people no longer fear starvation, they choose to eat for a whole variety of reasons, and these were not so different at the court of the Medici than they are at the food courts of Beverly Hills. Food is much more than a fuel; it is packed with meaning and symbolism. That ground-up tree bark in your morning oatmeal once had the scent of heaven, the grated tropical nut kernel topping your eggnog set in motion a world trading network, and those shriveled little berries in your pepper grinder gave the cue for Europe’s entry onto the world stage and its eventual conquest of the world. The origins of globalization can be traced directly to the spice trade.

R

ETROFITTING

E

DEN

It is often assumed that people’s taste preferences are conservative, and while this may be true for a particular individual, the cuisines of societies are regularly transformed within a generation or two. The fondness that many adult Americans exhibit for that sugary mélange of Crisco and cocoa powder called Oreos was most surely not shared by their parents. Italians as a whole were not obsessive pasta eaters until after the Second World War. Today, the eating styles of entire nations are in flux. And they are converging. It could be argued that the world—at least, that part of it that doesn’t fear starvation—is eating more alike than it has since the Middle Ages. Of course, food is only a small part of this phenomenon. There is a kind of modern-day, international gothic, not only in art and architecture (as the term is typically used by art historians) but also in food, music, fashion, and language. English is the new Latin. Hip-hop emanates from clubs in Nairobi and Mumbai. McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and their imitators dot the globe.