The Syme Papers (52 page)

Authors: Benjamin Markovits

‘

I

need not account – for

my every thought, my dear Tom,’ Sam

answered in a light tone, too weak for its purpose. Then he added

more heavily, ‘You are here on sufferance only –

all of you –

on

sufferance only.’

‘Turn to me when I speak to you!’ Tom said again, in a voice I had

never heard. Syme turned, somewhat cowed. ‘These are only some

calculations

–

Phidy and I sketched between us

–

concerning an

eclipse,’ he answered more gently. ‘It occurred to me

–

we could apply

a similar logic –

to the outer sphere

itself, which might explain …’

Tom was strangely agitated. ‘What right have you to speak to me of

sufferance, knowing as you do the daily sacrifices –

daily

–

I

make for

you in my absence, and all that absence necessitates, from my home?’

‘Hush,’ I urged again, more boldly now; and I ventured a word

between them for the first time.

‘

I

have never heard you speak this

way. Do not speak this way to him. Not now, Tom.’

He never so much as glanced at me. Sam turned and said, ‘Sit

down, Phidy. This does not concern you.’ And I sat down.

Tom swayed somewhat on his feet, and his voice had a thin rasp in

it, like the rattle of a cracked coin. The first cloud of a fever flew over

his head. He continued in a very bitter spirit that overleapt its cause,

pricked by some fear I could not see. ‘If it pleases you to plot palaces

and kingdoms with this weak-kneed calf of a German schoolboy, do

not expect my patience. I have come for your triumph, which you

seem so willing to exchange for the easy admiration of children and

the dying lust of a sailor’s widow. You have a speech to make tomor

row afternoon, a speech attended (through my exertions) by a man

named Ezekiel Harcourt, who is in the way of doing you a power of

good. If you intend to read a list of numbers at this gathering, you

may

continue. If not, TURN

TO THE WORK AT HAND.’

Syme did turn, but not towards his desk. ‘If you wish to speak –

of the easy admiration of schoolboys –

how

would you call the calf

love

of a gullible young journalist –

whom

I took on at his own

request –

out of my forbearance?’

‘Your salvation. Now turn to the work at hand.’

‘No,’

Sam said, instantly childish, and flung himself on the

ottoman in a heap.

Tom strode towards his bedchamber, and I shuffled aside to let

him pass. His coldness stung me deeply (

‘this’,

he called me, wrin

kling his nose) and I blushed at the recollection, but the rush of

blood brought with it a secret joy.

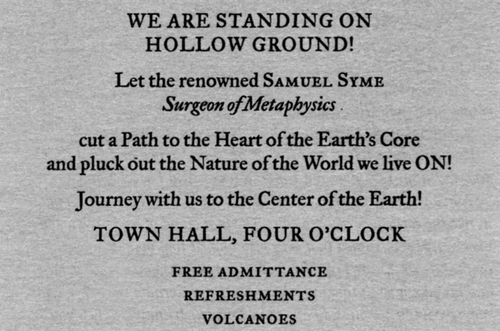

At dawn, in a chill fever, Tom pasted pamphlets advertising

Sam’s presence around the town, on lamp-posts and public trees.

Few were out to see them. Those who were saw the ink smeared in

the heavy air and a flaccid sheet of grey paper announcing:

The town hall, a cavern of a place, was filled with chairs from the

local school, at Tom’s arrangement. Naturally, given the subject of

Syme’s discourse, we could rarely avail ourselves of the church for a

platform; but the church came to us, as was not infrequently the

case. They formed a solitary battalion. No one else challenged to

meet them, except a spreading widow who thought Doomsday was

to be preached and a tottering old man with a sparse beard, like grey

sticks of straw, and afoul breath, who came for the relative coolness

of the great hall and the promise of refreshments.

The local chapter of the Oceanic Society provided red punch on

the neighbouring tables. Its chairman, Mr Cooling (the famous

nephew), met us in great apology. ‘It is too bad. I know it, I feel it

strongly, sir, but the truth of the matter is that old Mrs

Cumberland cannot venture out in the heat (her doctor wouldn’t

hear of it), can indeed scarcely lift her feet from basins of water

without someone upbraids her, at her age and girth. And she is by

way of being the leading light of our little organization. I am, as it

were, a lieutenant-commander, on board a vessel where the admiral

presides. I have preached and begged, sir

–

yes

sir!

–

to little effect,

for we are no better than schoolchildren when the master is away.

And as I said, sir, poor Mrs Cumberland; and to do my poor flock

(yes, that’s what I call them, between ourselves, sir, and Mrs

Cumberland) justice it is a whacking great heat to be going on with.

I can scarcely stand myself. Yes, I

will

take an early dip in the

punch if it’s all the same. We might as well ladle it out now to keep

the congregation happy. It is a great shame, sir, but as you can see

we should have a very warm, warm response, ha!, from the

Reverend Mr Kirkland’s flock. A great shame.’ There were nine of

us in all.

Mr Cooling bent a long leg and rose to the dusty platform,

walked over to the pulpit and began banging it. ‘Order, order, the

two hundred and sixteenth meeting of the Middletown Chapter of

the Oceanic Society is called to order, order.’ The fat lady sat up

very straight at that, but the Reverend’s congregation barely

stirred, leaned like horses towards the table of punch. No one had

been talking. Tom glanced slyly at me, from his chair on the corner

of the platform, and winked. (An apology?) I sat

alone in

a row

of

otherwise empty chairs.

There was no order or disorder to be called. We were all too hot

for either. Even Mr Cooling was too hot. His notes stuck under

his damp thumbs and his jumbled words fell in the heavy air

almost before they reached us,

like dropped sheets of paper:’…

rose to the rank of lieutenant in the 53rd, before being called to

God’s greater army

…

among the scientists battling … if I

might have a drink

…

having found the trapdoor into this little

planet of ours

…

Mr

Mooler,

if it wouldn’t trouble you

…

now

proposes, in

short

…

yes,

NOW, Mr

Mooler,

if you please

…

from a dizzying height of intellect, perhaps I should say depth

[chuckling], perhaps I should say depth indeed

…

thank you very

much, it is a trifle hot

…

proposes to open that door

…

yes,

if

you would be so kind

…

MOOLER.

’

Here he peers at a note from Tom. ‘Oh, I see, open that trapdoor

and descend like a thief into the, yes, into the heat of Nature. Into

the

heart.

Order Mr Syme a warm round. Samuel Syme.’ And he

went to the edge of the platform and lowered a stiff leg and sat down

beside me, whispering, ‘Most kind.’

Syme rose from his seat beside Tom and walked to the pulpit. He

drew inward at such shrunken occasions as these. Then he appeared

to me in his plainest dress, in the open, unmarked by grandness or

falseness or failure. Nothing remained but the scars of thought in his

features, the dignity of his figure, and the disappointment in his

address. He was heavy-hearted; still heavy with last night’s anger,

though a forgotten weight; heavier still with the heat and the

meagre crowd and the hopelessness of it all. But he was a brave man.

Perhaps more than anything else, he was a brave man. For once he

rose not

to

but

above

the occasion. ‘Ladies and gentlemen. It is a

pleasure to see such a fine representation of the Middletown elite here

today

–

despite the heat –

particularly Reverend Kirkland himself –

another expert, I believe –

in

internal fires.’ He always began a lec

ture to a small audience with a dig at the Church, to agitate interest

among them. ‘To you,’ he continued, in a phrase I had heard a dozen

times

before, ‘I have a most particular proposition.’

It was slow work and he worked on. The sweating widow soon

recognized her error, that no damnation was to come, though Sam

preached underground flames in abundance. She rose abruptly and

left; returned a minute later and ladled a dose of punch into one of

the glasses, drank it noisily, set it down noisily, and said noisily,

‘I’m sorry to interrupt,’

before departing once more. ‘Hell-fire;

indeed they’ll see Hell-fire,’

Tom says he heard her mutter.

Syme soldiered on. ‘Between the second and the third spheres –

no,

that is to say

(yes,

you’re quite right, Tom), I was about to

mislead

you, gentlemen –

between the fifth and the sixth spheres

–

that must

have puzzled you for a moment …’ I ceased to hear him as I shifted

to one side, stretched my tired legs and gazed out of the heavy win

dows into the white summer air. I heard silence surround us like

sea-noise, larger than any stir we could muster.

Syme buzzed on. ‘Volcanic eruptions

–

once ascribed to the anger

of gods

–

must now be seen in

their true light

–

free

of their hideous

mythological

drapings

–

like nothing so much as the costumes of

an amateur

theatrical

society. They must now be seen as the prod

uct

of gases

–

released when

–

in

inverted eclipse

–

two vacuii

of the

outer crowns overlap. What is at stake, gentlemen? Why have I

troubled you on this heavy afternoon

–

a

fly in

your midst

–

buzzing, settling and unsettling, buzzing, ever disturbing? Why

can’t I rest? Why have I kept you from the cool waters waiting on the

table

–

so generously provided by Mr

Cooling

–

that on a day

like

this must have drawn more of your glances –

and more of mine,

I’m

afraid …’

Here a small boy slithered from his father’s lap and dipped a quick

cup into the silver bowl, while his father hissed, ‘Henry!’ only to

take a long draught when the boy returned to him, carefully bal

ancing the heavy drink. ‘He said there was going to be volcanoes,’ the

boy announced, to no one in particular, in obscure apology.

Syme had lost his place

on the page. ‘An omission

–

my dear boy

–

entirely of my own neglect,

I’m afraid. But to proceed

– I

will not

detain you much longer

–

indeed, I have said more than I had come

to say. My passion carries me with it.’ Never to me did a man’s pas

sion seem capable of so little weight, and he smiled wearily as he

said it. ‘The objection to my theories –

theories that, if we are to

believe them, earnestly, with more than a mere religious faith,

would shake the very ground we stand

on to its

core –

the objection

that I have heard more than any

other is not

scientific –

as indeed it

could not be, since the theories themselves bear no scientific

refutation –

but psychological, or

moral,

if you prefer such a term.’

He had lost us all by now, though he rose to what followed, and I

thought he could never lose me again.

‘Churchmen, widows, children, sailors, newspapermen, profes

sors,

schoolteachers, wives

–

all reproach me with one thing.

“From what arrogance do you speak?” they ask. “From what high

arrogance do you preach –

against the thousand-year-old traditions

of your people

–

your universities –

and your God? Have you alone

seen the truth –

where so many great men

have been blind?” And I

answer them: “From the courage of my two eyes –

my thoughts

–

and the hands He has given me for digging.” I ask instead, “With

what arrogance dare I refuse? With what arrogance dare I deny the

only gifts I am

certain of –

the gifts of our great God –

contenting

me with another man’s answers – as

I rely

on the cook to buy

the

butter or dress a roast?”’