The Swing Book (5 page)

Authors: Degen Pener

As Americans fought the war, however, Miller’s music took on a deep meaning for both civilians and soldiers. In 1942 Miller

gave up his money-making orchestra, enlisted in the army, and started his own military band. A model patriot, he boosted morale

playing for the troops throughout Europe. Swing, in general, began to be seen as a representation of the values that America

was defending. As President Franklin Roosevelt said at the time, music could “inspire a fervor for the spiritual values in

our way of life and … strengthen democracy.” Betty Grable and Rita Hay-worth (both of whom married bandleaders, Harry James

and Artie Shaw, respectively) and swing singer

Lena Horne

became the most popular pinups. The

Andrews Sisters

had a hit with “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.” After the Nazis labeled jazz “nigger-jew” music, swing (as later depicted in the

movie

Swing Kids

) became an anti-Fascist symbol. During the war, as American soldiers moved into Europe, they turned Europeans on to the music

as never before. However, the war years also added a new conservatism to swing. The boys overseas generally wanted to hear

the songs that they already knew from home, not new tunes. When Miller died in an airplane crash in 1944, he was justly hailed

as a hero. But many saw his music as the harbinger of things to come. “I think that band was like the beginning of the end.

It was a mechanized version of what they called jazz music,” said Artie Shaw in

Dialogues in Swing.

Soon after the end of the war, and seemingly out of nowhere, the swing business started to collapse. By late 1946 Woody Herman,

Harry James, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Carter, and

Les Brown

had all disbanded their orchestras. Soon after, Cab Calloway, Charlie Barnet, and Artie Shaw called it quits too. The Basie

band held on until 1950. But an era had clearly passed. Trumpeter Johnny Coppola recalls playing a late-forties date with

bandleader Stan Kenton in Oakland. “The crowds weren’t there,” he says. “Kenton was in shock. He looked around and said, ‘Where

is everybody?’ They were home watching TV.”

Actually, television was just one of many reasons that the big bands fell by the wayside. A 30 percent cabaret tax instituted

in 1944 raised the price of going out. GIs returning from the war, once the young fans of swing, were older and looking to

start families. The war effort had also put a major strain on the bands. They were hampered from touring by the rationing

of gasoline and rubber, while losing huge numbers of musicians to conscription. “The war took all the men out of there,” says

Norma Miller. The manufacture of jukeboxes was temporarily stopped, and the production of records was cut 30 percent. Meanwhile,

a standoff between the American Federation of Musicians union and the music industry, which created a ban on recordings by

orchestras, crippled swing as well. Begun in late 1942, the union strike lasted more than a year. While some big bands held

on after the war, their cultural dominance had ended.

Despite the effect of all these social changes, however, music was simply evolving on its own, the way it always does, decade

after decade. In jazz, in the forties, a New Orleans Dixieland revival took off. This interest in earlier jazz was itself

a roots revival, reflecting a feeling that swing had become empty and inauthentic. At the same time, bop, many of whose proponents

had been swing band players (the foremost being Dizzy Gillespie), ushered in an exciting new sound that, unfortunately, with

its emphasis on dissonance and its relative lack of melody, wasn’t danceable. “When I came out of the army we got a gig working

with Dizzy Gillespie’s band and afterward I said, ‘Dizzy what is this stuff? What the f — is that?’ I did not understand that

music at all. So this is one thing that killed swing,” recalls Frankie Manning.

Just as jazz and dance split apart, so did jazz and popular music. Vocalists, not orchestras, began to dominate the charts.

Previously, during the height of the big band era, singers had been no more important than musicians. Often they felt like

mere accessories. “The bandleader never wanted to be outshone by anybody. So most of the male vocalists had to stand there,

ramrod stiff, sing a chorus, go sit down, get up, sing the last chorus, and sit down again,” recalls Frankie Laine, one of

the biggest new solo singers of the late forties and early fifties.

Peggy Lee,

Patti Page,

Nat King Cole,

and others benefited from the change, but the one man to kick it all off was

Frank Sinatra.

After quitting Tommy Dorsey’s band and creating a sensation at New York’s Paramount Theater in the early forties, Sinatra

made the momentous decision to strike out on his own. “One could see the writing on the wall: the focus now was going to be

on an individual instead of on 16 men,” said jazz singer

Mel Tormé

in

Dialogues in Swing.

In a huge reversal, the band was now mere backup to the singer. While many of these singers still performed music that swung,

they were more likely to be doing it at a lounge than in a dance hall. Jazz still enjoyed periods of popular upswing—among

the most famous were Ellington’s 1956 appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival and Ella Fitzgerald’s songbook recordings. A

handful of reconstituted bands, such as those of Count Basie and Les Brown, enjoyed success too. But according to David W.

Stowe’s

Swing Changes,

“None of these ensembles … sought to connect with the dancers swing had reached.”

While the big bands were effectively over, however, swing wasn’t totally in eclipse. Driven by the influence of Count Basie’s

fast-moving blues sound, a new musical form grew out of swing. You could catch a glimpse of it in 1942 when Illinois Jacquet

honked and wailed his way through his sax solo on the Lionel Hampton tune “Flying Home.” By the end of the forties, it even

had its own name, jump blues, a powerful, hard-rocking mix of jazz arrangements and solos with the deep soul of the blues.

The saxes blasted and the horns keened like never before. The singers shouted the lyrics, and a strong backbeat pushed the

music. And it was all firmly rooted in swing. Jump blues’ most famous artist,

Louis Jordan,

who sold millions of records after the war, had been a saxophonist with Chick Webb. The trumpeter

Louis Prima

had written “Sing, Sing, Sing” for Goodman. And singer

Wynonie Harris

had performed for Lucky Millinder’s swing band. “Whether you are stompin’ or you’re jumpin’ or you’re swingin’ …, you’re

talking about the same type of beat, the same type of groove, and the same type of tempo,” says Albert Murray in the documentary

Bluesland.

But Jordan—whose smash hits included “Caldonia” and “Choo Choo Ch’Boogie” —led the way in paring down the size of the orchestras,

finding a big sound with his new seven-piece combo.

In doing so, he was a decisive catalyst in the creation of both rock ’n’ roll and R&B. Back in the day, promoters began using

the terms

swing

and

rock

fairly interchangeably to describe jump blues bands like Jordan’s. Recalls Claude Trenier, leader of the jump band the

Treniers,

who sang with the Jimmie Lunceford Orchestra: “We went to the Blue Note in Chicago and the owner said what kind of music

was that and we said we’re just having fun. It’s swinging. But he put on the marquee ‘The rock and rollin’ Treniers.’ They

just changed the name.” Once the rock era exploded in the mid-fifties, Jordan’s influence was still pervasive. Rock legend

Chuck Berry has said, “I identify myself with Louis Jordan more than any other artist.” “He was everything,” James Brown once

said, as quoted in John Chilton’s Jordan biography

Let the Good Times Roll.

And while rocker Bill Haley never acknowledged Jordan’s influence on his music, Jordan himself claimed, “When Bill Haley

came along in 1953 he was doing the same shuffle boogie I was.” Indeed, in the last few years there’s been a major reevaluation

of rock’s pioneers afoot. It’s clear that as much as Haley and even Elvis were rocking, they were swinging too. Adds bandleader

Bill Elliott, “What people forget is that all through the fifties, even though there was rock and roll, the dancing was still

essentially swing dancing.” By now, everyone knows the story of how white musicians and record labels repackaged black R&B

and created rock in the fifties. But it’s possible to trace a line from rock back to R&B and then further back to swing. And

that’s exactly the path that today’s neoswingers took to find their musical roots.

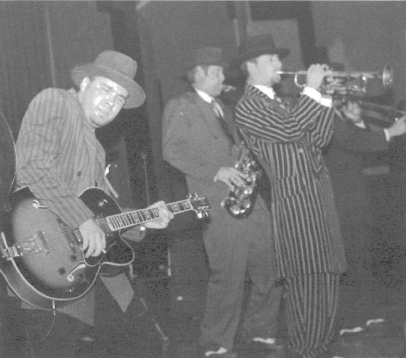

Big Bad Voodoo Daddy.

(M

ARK

J

ORDAN

)

L

et’s get one thing perfectly clear: swing wasn’t brought back by a Gap ad. The origins of the swing revival date back at least

two decades. It began on a grassroots level and has slowly, steadily, and within the last several years, furiously grown and

deepened into the full-fledged movement it is today. A true rediscovery of the dance, music, and style of the original era,

the resurgence first sprang up among small pockets of like-minded but isolated people scattered in cities all across the world.

Dancers from Stockholm and London to New York and Los Angeles began learning and falling in love with the real Savoy-style

Lindy Hop, the crazed jitterbugging and dangerous aerials that once had social critics in apoplexy. Musicians up and down

the West Coast searched for and embraced the hotter facets of swing, the screaming improvisational jazz riffs and licks that

back in the day had shocked the establishment. And also out in California, scenesters started once again wearing the most

defiant and colorful fashions of the forties: the zoot suit, an outfit that had once incited riots (see chapter 6). Who are

the people who brought back swing? In the best of ways, they’re a motley crew of jazz aficionados, former punk rockers, rockabilly

and ska fanatics; hard-edged greasers and squeaky clean nostalgics; street-kid dancers and ballroom refugees; history buffs;

and best of all, some of the era’s original musicians and Lindy Hoppers. What they all had in common was a desire to go back

to the roots of swing, and what they found was that it could have a freshness and power all over again.

Fresh was not what you would call the swing that was hanging around before the revival happened. Swing, of course, had never

really died out. For years it was kept alive by society dance bands across the country who trotted out old chestnuts like

“In the Mood” over and over again at weddings, charity benefits, and golden anniversary parties. The average kid growing up

in the seventies couldn’t be blamed for equating swing with a graying Guy Lombardo trying to liven up New Year’s Eve on television.

Or, even worse, with the bubbly schmaltz of

The Lawrence Welk Show.

By the eighties and nineties, however, even those saccharine reminders of big band’s glory days had exited the stage. No

less a person than Duke Ellington’s foremost modern-day champion, Wynton Marsalis, artistic director of New York’s Jazz at

Lincoln Center, has said that when he was young the name Ellington called to mind “old people and Geritol.” Adds Jack Vaughn,

president of the neoswing label Slimstyle Records, “The swing music of old was marginalized by movie soundtracks and car commercials.

It became background music.” And the dance was in even worse shape. Most ballroom studios around the country, while still

teaching swing, promulgated a watered-down, lifeless version of the dance that was short on improvisation and big on routine.

“It was often just a basic six-count East Coast,” says dance teacher and historian Margaret Batiuchok, one of the people most

responsible for bringing back the Lindy.

Over the years, a number of new singers, from Bette Midler to Harry Connick Jr., have helped popularize the era’s standards,

though often the choice of material has focused on the sweeter, more conservative songs. Think of Midler’s rousing cover of

the Andrews Sisters’ “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” in 1971; Midler also sang with the Lionel Hampton band on Broadway in 1976.

Around the same time, the Manhattan Transfer’s jazzy vocals brought back hits such as the Glenn Miller classic “Tuxedo Junction.”

In the mid-eighties Linda Ronstadt recorded a slew of old-fashioned tunes on a trio of albums produced by famous Sinatra arranger

Nelson Riddle. And in 1989 swing got an enormous boost with the release of the hit soundtrack from

When Harry Met Sally,

featuring a then-twenty-two-year-old Harry Connick Jr. crooning in full Sinatra mode. Starting in the mid-eighties, a traditionalist

revival, led by Marsalis, also began making its mark on the jazz world.