The Swerve (38 page)

Authors: Stephen Greenblatt

Natural History

(chap. 35), the Roman author Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) noted a vogue in his time for portrait busts of Epicurus.

De varietate fortunae

. The work, written when Poggio was sixty-eight years old, eloquently surveys the ruins of ancient Roman greatness.

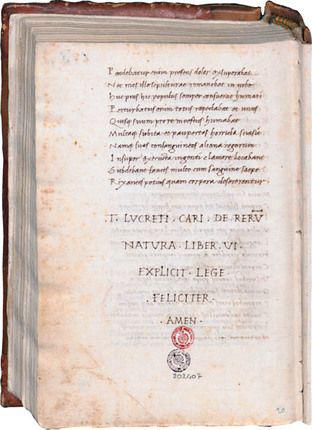

On the Nature of Things

to a close with the customary word “Explicit” (from the Latin for “unrolled”). He enjoins the reader to “read happily” (“Lege feliciter”) and adds—in some tension with the spirit of Lucretius’ poem—a pious “Amen.”

Portrait of young Poggio

.

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Ms. Strozzi 50, 1 recto. By permission of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali with all rights reserved

Poggio’s transcription of Cicero

.

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Ms. Laur.Plut.48.22, 121 recto. By permission of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali with all rights reserved

Seated Hermes

.

Alinari / Art Resource, NY

Resting Hermes

.

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Bust of Epicurus

.

By courtesy of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli / Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei

The Flagellation of Christ

,

Michael Pacher

.

The Bridgeman Art Library International

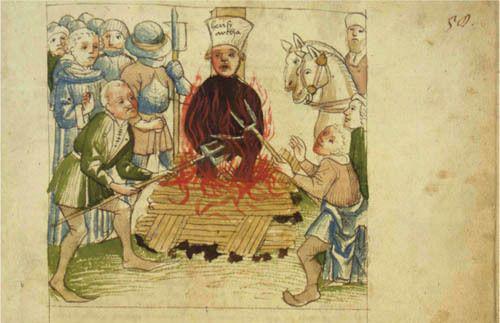

Heretic Hus, burned at the stake

.

By courtesy of the Constance Rosgartenmuseum

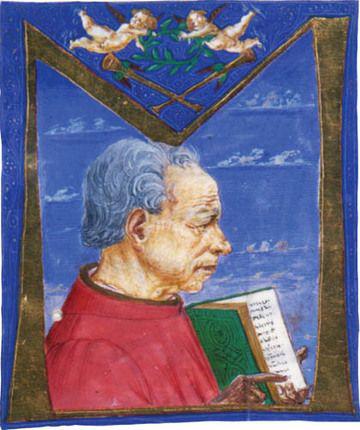

Portrait of elderly Poggio

. ©

2011 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Ms. lat.224, 2 recto

Niccoli’s transcription of

On the Nature of Things. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Ms. Laur.Plut.35.30, 164 verso. By permission of the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali with all rights reserved

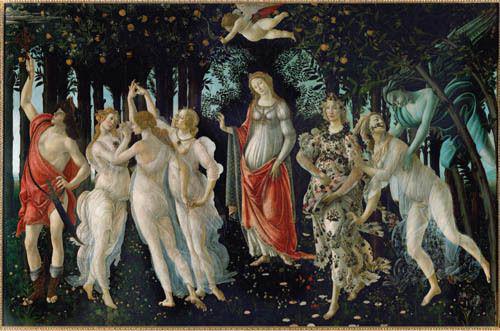

La Primavera

,

Sandro Botticelli

.

Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

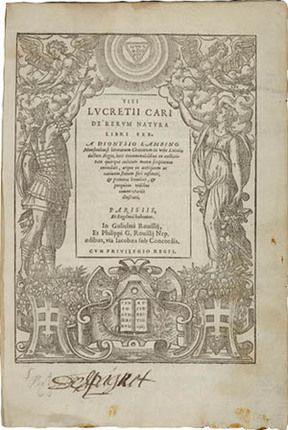

Montaigne’s edition of Lucretius

.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library

Ettore Ferrari’s statue of Giordano Bruno

.

Photograph by Isaac Vita Kohn

PREFACE1

Lucretius,

On the Nature of Things

, trans. Martin Ferguson Smith (London: Sphere Books, 1969; rev. edn., Indianapolis: Hackett, 2001), 1:12–20. I have consulted the modern English translations of H. A. J. Munro (1914), W. H. D. Rouse, rev. Martin Ferguson Smith (1975, 1992), Frank O. Copley (1977), Ronald Melville (1997), A. E. Stallings (2007), and David Slavitt (2008). Among earlier English translations I have consulted those of John Evelyn (1620–1706), Lucy Hutchinson (1620–1681), John Dryden (1631–1700), and Thomas Creech (1659–1700). Of these translations Dryden’s is the best, but, in addition to the fact that he only translated small portions of the poem (615 lines in all, less than 10 percent of the total), his language often renders Lucretius difficult for the modern reader to grasp. For ease of access, unless otherwise indicated, I have used Smith’s 2001 prose translation, and I have cited the lines in the Latin text given in the readily available Loeb edition—Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1975.2

On the Nature of Things

5:737–40. Venus’ “winged harbinger” is Cupid, whom Botticelli depicts blindfolded and aiming his winged arrow; Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers, strews blossoms gathered in the folds of her exquisite dress; and Zephyr, the god of the fecundating west wind, is reaching for the nymph Chloris. On Lucretius’ influence on Botticelli, mediated by the humanist Poliziano, see Charles Dempsey,

The Portrayal of Love: Botticelli’s “Primavera” and Humanist Culture at the Time of Lorenzo the Magnificent

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), esp. pp. 36–49; Horst Bredekamp,

Botticelli: Primavera. Florenz als Garten der Venus

(Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Verlag GmbH, 1988); and Aby Warburg’s seminal 1893 essay,

“Sandro

Botticelli’s

Birth of Venus

and

Spring

: An Examination of Concepts of Antiquity in the Italian Early Renaissance,” in

The Revival of Pagan Antiquity

, ed. Kurt W. Forster, trans. David Britt (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1999), pp. 88–156.3

A total of 558 letters by Poggio, addressed to 172 different correspondents, survive. In a letter written in July 1417 congratulating Poggio on his discoveries, Francesco Barbaro refers to a letter about the journey of discovery that Poggio had sent to “our fine and learned friend Guarinus of Verona”—

Two Renaissance Book Hunters: The Letters of Poggius Bracciolini to Nicolaus de Nicolis

, trans. Phyllis Walter Goodhart Gordan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1974), p. 201. For Poggio’s letters, see Poggio Bracciolini,

Lettere

, ed. Helene Harth, 3 vols. (Florence: Olschki, 1984).CHAPTER ONE: THE BOOK HUNTER1

On Poggio’s appearance, see

Poggio Bracciolini 1380–1980: Nel VI centenario della nascita

, Instituto Nazionale di Studi Sul Rinascimento, vol. 7 (Florence: Sansoni, 1982) and

Un Toscano del ’400 Poggio Bracciolini, 1380–1459

, ed. Patrizia Castelli (Terranuova Bracciolini: Administrazione Comunale, 1980). The principal biographical source is Ernst Walser,

Poggius Florentinus: Leben und Werke

(Hildesheim: George Olms, 1974).2

On curiosity as a sin and the complex process of rehabilitating it, see Hans Blumenberg,

The Legitimacy of the Modern Age

, trans. Robert M. Wallace (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983; orig. German edn. 1966), pp. 229–453.3

Eustace J. Kitts,

In the Days of the Councils: A Sketch of the Life and Times of Baldassare Cossa

(

Afterward Pope John the Twenty-Third

) (London: Archibald Constable & Co., 1908), p. 359.4

Peter Partner,

The Pope’s Men: The Papal Civil Service in the Renaissance

(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), p. 54.5

Lauro Martines,

The Social World of the Florentine Humanists, 1390–1460

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963), pp. 123–27.6

In 1416 he evidently tried, with the others in the curia, to secure a benefice for himself, but the grant was controversial and in the end was not awarded. Apparently, he could also have taken a position as Scriptor in the new papacy of Martin V, but he refused, regarding it as a demotion from his position as secretary—Walser,

Poggius Florentinus

, pp. 42ff.CHAPTER TWO: THE MOMENT OF DISCOVERY1

Nicholas Mann, “The Origins of Humanism,” in

The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism

, ed. Jill Kraye (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 11. On Poggio’s response to Petrarch, see Riccardo Fubini,

Humanism and Secularization: From Petrarch to Valla

, Duke Monographs in Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 18 (Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2003). On the development of Italian humanism, see John Addington Symonds,

The Revival of Learning

(New York: H. Holt, 1908; repr. 1960); Wallace K. Ferguson,

The Renaissance in Historical Thought: Five Centuries of Interpretation

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1948); Paul Oskar Kristeller, “The Impact of Early Italian Humanism on Thought and Learning,” in Bernard S. Levy, ed.

Developments in the Early Renaissance

(Albany: State University of New York Press, 1972), pp. 120–57; Charles Trinkaus,

The Scope of Renaissance Humanism

(Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1983); Anthony Grafton and Lisa Jardine,

From Humanism to the Humanities: Education and the Liberal Arts in Fifteenth-and Sixteenth-Century Europe

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986); Peter Burke, “The Spread of Italian Humanism,” in Anthony Goodman and Angus Mackay, eds.,

The Impact of Humanism on Western Europe

(London: Longman, 1990), pp. 1–22; Ronald G. Witt, “

In the Footsteps of the Ancients

”

: The Origins of Humanism from Lovato to Bruni, Studies in Medieval and Reformation Thought

, ed. Heiko A. Oberman, vol. 74 (Leiden: Brill, 2000); and Riccardo, Fubini,

L’Umanesimo Italiano e I Suoi Storici

(Milan: Franco Angeli Storia, 2001).2

Quintilian,

Institutio Oratoria

(

The Orator’s Education

), ed. and trans. Donald A. Russell, Loeb Classical Library, 127 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 10.1, pp. 299ff. Though a complete (or nearly complete) copy of Quintilian was only found—by Poggio Bracciolini—in 1516, book X, with its lists of Greek and Roman writers, circulated throughout the Middle

Ages

. Quintilian remarks of Macer and Lucretius that “Each is elegant on his own subject, but the former is prosaic and the latter difficult,” p. 299.3

Robert A. Kaster,

Guardians of Language: The Grammarian and Society in Late Antiquity

(Berkeley and London: University of California Press, 1988). Estimates of literacy rates in earlier societies are notoriously unreliable. Kaster, citing the research of Richard Duncan-Jones, concludes: “the great majority of the empire’s inhabitants were illiterate in the classical languages.” The figures for the first three centuries

CE

suggest upwards of 70 percent illiteracy, though with many regional differences. There are similar figures in Kim Haines-Eitzen,

Guardians of Letters: Literacy, Power, and the Transmitters of Early Christian Literature

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), though Haines-Eitzen has even lower literacy levels (10 percent perhaps). See also Robin Lane Fox, “Literacy and Power in Early Christianity,” in Alan K. Bowman and Greg Woolf, eds.,

Literacy and Power in the Ancient World

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).4

Cited in Fox, “Literacy and Power,” p. 147.5

The Rule does include a provision for those who simply cannot abide reading: “If anyone is so remiss and indolent that he is unwilling or unable to study or to read, he is to be given some work in order that he may not be idle”—

The Rule of Benedict

, trans. by Monks of Glenstal Abbey (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1982), 48:223.6

John Cassian,

The Institutes

, trans. Boniface Ramsey (New York: Newman Press, 2000), 10:2.7

The Rule of Benedict

, 48:19–20. I have amended the translation given, “as a warning to others,” to capture what I take to be the actual sense of the Latin:

ut ceteri timeant

.8

Spiritum elationis

: the translators render these words as “spirit of vanity” but I believe that “elation” or “exaltation” is the principal sense here.9

The Rule of Benedict

, 38:5–7.10

Ibid., 38:8.11

Ibid., 38:9.12

Leila Avrin,

Scribes, Script and Books: The Book Arts from Antiquity to the Renaissance

(Chicago and London: American Library Association and the British Library: 1991), p. 324. The manuscript is in Barcelona.13

On the larger context of Poggio’s handwriting, see Berthold L. Ullman,

The Origin and Development of Humanistic Script

(Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 1960). For a valuable introduction, see Martin Davies, “Humanism in Script and Print in the Fifteenth Century,” in

The Cambridge Companion to Renaissance Humanism

, pp. 47–62.14

Bartolomeo served as secretary in 1414; Poggio the following year—Partner,

The Pope’s Men

, pp. 218, 222.15

Gordan,

Two Renaissance Book Hunters

, pp. 208–9 (letter to Ambrogio Traversari).16

Ibid, p. 210.17

Eustace J. Kitts,

In the Days of the Councils: A Sketch of the Life and Times of Baldassare Cossa

(London: Archibald Constable & Co., 1908), p. 69.18

Cited in W. M. Shepherd,

The Life of Poggio Bracciolini

(Liverpool: Longman et al., 1837), p. 168.19

Avrin,

Scribes, Script and Books

, p. 224. The scribe in question actually used “vellum,” not parchment, but it must have been a particularly miserable vellum.20

Ibid.21

Quoted in George Haven Putnam,

Books and Their Makers During the Middle Ages

, 2 vols. (New York: Hillary House, 1962; repr. of 1896–98 edn.) 1:61.22

The great monastery at Bobbio, in the north of Italy, had a celebrated library: a catalogue drawn up at the end of the ninth century includes many rare ancient texts, including a copy of Lucretius. But most of these have disappeared, presumably scraped away to make room for the gospels and psalters that served the community. Bernhard Bischhoff writes: “Many ancient texts were buried

when

their codices were palimsested at Bobbio, which had abandoned the rule of Columbanus for the rule of Benedict. A catalogue from the end of the ninth century informs us that Bobbio possessed at that time one of the most extensive libraries in the West, including many grammatical treatises as well as rare poetical works. The sole copy of Septimius Serenus’

De runalibus

, an elaborate poem from the age of Hadrian, was lost. Copies of Lucretius and Valerius Flaccus seem to have disappeared without Italian copies having been made. Poggio eventually discovered these works in Germany”—

Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 151.23

A strong alternative candidate is the Abbey of Murbach, in southern Alsace. By the middle of the ninth century, Murbach, founded in 727, had become an important center of scholarship and is known to have possessed a copy of Lucretius. The challenge facing Poggio would have been roughly the same in any monastic library he approached.24

In the context of the current book, the most intriguing comment comes in Rabanus’s prose preface to his fascinating collection of acrostic poems in praise of the Cross, composed in 810. Rabanus writes that his poems include the rhetorical figure of

synalpha

, the contraction of two syllables into one. This is a figure, he explains,

Quod et Titus Lucretius non raro fecisse invenitur

—“which is frequently found in Titus Lucretius.” Quoted in David Ganz, “Lucretius in the Carolingian Age: The Leiden Manuscripts and Their Carolingian Readers,” in Claudine A. Chavannes-Mazel and Margaret M. Smith, eds.,

Medieval Manuscripts of the Latin Classics: Production and Use

, Proceedings of the Seminar in the History of the Book to 1500, Leiden, 1993 (Los Altos Hills, CA: Anderson-Lovelace, 1996), 99.25

Pliny the Younger,

Letters

, 3.7.26

The humanists might have picked up shadowy signs of the poem’s continued existence. Macrobius, in the early fifth century

CE

, quotes a few lines in his

Saturnalia

(see George Hadzsits,

Lucretius and His Influence

[New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1935]), as does Isidore of Seville’s vast

Etymologiae

in the early seventh century. Other moments in which the work surfaced briefly will be mentioned below, but it would have been rash for anyone in

the

early fifteenth century to believe that the entire poem would be found.