The Sun Gods (25 page)

Authors: Jay Rubin

Leaving the suitcase by the door, Mitsuko trudged across the baking desert sands to see Billy one more time at the hospital. The sun was burning through the shoulders of her blouse, and several times she mopped the perspiration from her brow.

“What's wrong?” Billy said immediately when she approached his bed with tear-filled eyes. She did not have the courage to tell him. Yoshiko had agreed to make excuses for her until Tom arrived on Wednesday.

“Nothing,” she said, trying to smile. “I think I may be catching a cold.”

“Oh,” Billy replied, but he did not return her smile.

“I brought you something,” she said, sitting on the edge of the bed with her feet dangling above the floor.

“It's not a going-away present, is it?”

“No, it's just a present.”

She drew the mirror in its case from the pocket of her dress and handed it to him. He did not reach for it.

“What is it?”

“Something you like. See for yourself.”

At last, he stretched his hand out and took the case, working the flap loose from beneath the narrow band that held it closed. The mirror slipped easily into his small hand.

“The mirror?” he asked, holding it at arm's length.

“That's right,” she said. “Look at yourself.”

He brought it closer to his face.

“Now look at the back.”

“The sun,” he muttered, touching the carved figure.

“And Nils' goose. Just what you wanted.”

He did not reply, but he turned it in his hand, running his fingers over the wood and studying his image in the little circle.

“You keep it,” he said at last. “I don't like it.”

He tried to thrust it into her hand.

“No. I want you to have it. I made one for myself just like it. We can both have one.”

“Take it back,” he whimpered. “I don't want you to go away.”

Before she could lie to him again, he flung the mirror across the aisle. It clanged against the pipe frame of the bed opposite, and dropped to the wooden floor with a crash of glass.

“Don't go, Mommy, please don't go,” he wailed, wrapping his arms around her neck.

She held him tightly, praying with all her might. Let the sun explode. Let it wrap the earth in its blazing embrace. Let it fuse this hate-filled globe into a single, molten mass, ending war and parting and suffering forever.

PART FIVE:

1959

26

THEY USUALLY MET

at midnight, after Bill finished work at the restaurant. They would go to quiet places, where Frank would wander back freely across the years, his black, intense eyes staring out into the night. The year was no longer 1959 but 1942, when Frank first met Mitsuko at Puyallup, or 1943, when Frank left his hospital bed in Minidoka to find that Mitsuko had returned to Japan on a repatriation ship.

As Frank led him through the dark passageways of the past, Bill could almost hear Mitsuko singing to him, but it was as if they were on opposite banks of a rushing stream. Her lips were moving. The song was for him. But the melody never reached him.

Frank could do nothing to help him hear it. “We were living in that tiny vacuum world in Minidoka. It was only after I started looking for her that I realized how little I actually knew about her.”

“When did you start looking for her?” Bill pressed him.

“Not for several years. I was angry with her, angry with everything. That's why I joined the 442nd. I figured I'd just go out there and get killed and it would be all over. They sent me to Bruyéres. That's where this happened.” He patted the empty sleeve. “After the war, the government paid for me to finish school. They paid me for my arm, too. I had some pretty good cash for a while. Bought myself a fancy car.”

“The DeSoto?”

“The DeSoto.” He smiled. “A lot of the other guys bought cars, too, but they frittered their money away. There was a lot of anger. The government had locked up our families and sent us out to die, but when it was all over, it was the same old story: no jobs for Japs. So I went back to school. Majored in economics at the U.W. Then I tried working for Boeing for a while, but I didn't have the engineering background to go very far with them. Besides, I wasn't too crazy about the military side of things at Boeing. I started investing on my own. I did all right for myself. Even got a pretty wife.”

“You're married?”

“No, not anymore.”

“Oh. I'm sorry.”

“Yeah, so was I. When my marriage went sour, I realized I hadn't ever gotten over Mitsuko and started looking for her. By then, it was already 1953 and I hadn't seen or heard anything about her in ten years.”

“Nineteen fifty-three,” said Bill. “I must have been fifteen then. That's when I saw you at the bus stop, isn't it?”

Frank nodded. “I had almost nothing to go on. I knew her sister and brother-in-lawâ”

“She had a sister?”

“Her name was Yoshiko. Husband was Goro Nomura.”

“Doesn't ring a bell.”

“I figured they would have come back to Seattle, but they weren't in the phone book. I knew both the husband and the wife had been active in the Minidoka protestant church, but that was some kind of united church and I didn't know which one they had actually belonged to in Seattle. I tried calling a few and asking for them, but no luck. A couple of the Japanese churches never got off the ground again after the war. You knowâtheir people went East or the Issei members died off.”

“Issei?”

“First-generation Japanese in America, the ones who immigrated. I'm a Niseiâsecond generation, but the first generation born here. A lot of the ministers were old, and some of the Issei just didn't make it through the winters or summers in the desert. That's what happened to the Japanese Christian Church. I'm almost certain that's the one the Nomuras would have attended. It's still over there on Terrace, all boarded up.”

“What a shameâfor them and for us.”

“The more churches they close, the better if you ask me,” Frank spat. “I'm amazed anybody could have come through the war thinking they had any kind of god watching over them.”

“It's not that easy to give up something you've always lived with,” Bill said.

“You just have to think about it with an open mind. It takes about ten seconds to see what nonsense it is.”

“Yes, but ⦔ Bill was not sure enough of where he stood on these matters to become involved in a debate. His father had seriously shaken his faith, and what Frank had been telling him dealt it another blow. But still, doing ministry work in Japan seemed like a good ideaâall the more so since he now knew that Mitsuko had gone back there. Bill said, “You were talking about your search.”

Frank looked at him and chuckled. “Sorry,” he muttered. “Religion's a sore spot with me. Still, it's got something to do with my search, too, because next I went to see your father.”

Bill had to look away, but Frank went on speaking as if he had noticed nothing.

“I really hadn't wanted to approach your father except as a last resort. I figured I could at least learn the name of his old congregation and get in touch with those people. He was easy enough to find in the phone book, so I went to see him in Magnolia. He didn't want to tell me anything. He practically threw me out.”

“I'm not surprised,” said Bill with a scowl. “He didn't want to be reminded of what he'd done.”

“As long as I was in Magnolia, I thought it might be some consolation if I could get a glimpse of you. You were a great little kid. I always liked you, so I drove over there and hung around outside for a few hours. Finally it dawned on me you weren't a little kid anymore, and I wasn't going to see you except coming or going to school. I tried again the next morning early. The weather was bad, so I had to drive right up to the curb. Sorry. I must have scared the daylights out of you.”

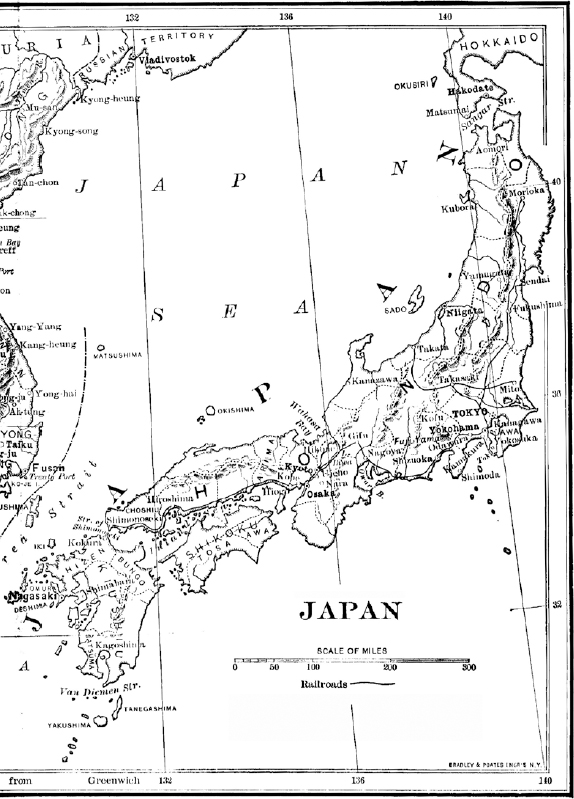

Frank spent a whole evening describing to Bill a fruitless two-week trip he had made to Tokyo after failing to turn up anything in Seattle.

“I don't know why I went,” he said. “A kind of sentimental journey, I suppose. I didn't know her last nameâshe was Mitsuko Morton, as far as I knewâand it wasn't likely she would have kept the foreign name in Japan. I tried the American Embassy, but they couldn't help at all. About the only thing I had to go on was the name of her sister and brother-in-law, but I can't read the language, and my spoken Japanese is a mess, so I hired a girl to go through the Tokyo phone book and try calling all the Nomuras. You should see how many Nomuras there are in the Tokyo phone bookâand that was back when not many people in Japan had phones. None of them knew Goro or Yoshiko. Of course, maybe they weren't even in Tokyo. Talk about looking for a needle in a haystack!”

One of the few mementos Frank still had from Minidoka was a brittle, yellowed copy of the camp newspaper, the

Irrigator

, with a Japanese section that had been written by Mitsuko herself. Holding the fragile sheet, Bill felt he could almost touch the hands of the woman who had inscribed the graceful characters.

“She designed the masthead, too,” Frank said. “She was a very talented lady. Used to make you toy boats and things. I don't suppose you've got any of those hanging around.”

Bill shook his head. The Japanese masthead was like a little woodblock print, with a meandering stream and cattails, a water tower and some low buildings sketched in behind the two vertically-written words “Minidoka” and “Irrigator.” Oddly, the name of the camp was spelled “Minedoka” in Japanese. Maybe it just sounded more natural that way.

Turning back to the English section, Bill said, “Here's an article on a Gallup poll.” He could hardly believe the figures. “Thirty-one percent were opposed to letting

any

Japanese-Americans come back to their homes after the war! That's incredible!”

“It still burns me up to think about it.”

“What hatred there must have been! But at least the relocation camps weren't as bad as the Nazi concentration camps,” Bill offered hopefully.

“How do

you

know?” Frank shot back, dark eyes burning past the sharp curve of his nose.

“Well, they didn't gas people.”

“No, but

we

didn't know that at the time. And the Jews didn't know they would be gassed. We went just like the Jewsâdocile, cooperative, good little Japs. We were plain lucky General DeWitt had his superiors to answer to. If he'd had his way, he'd have buried us all out there in the desert.”

The more he learned from Frank, the more impatient Bill became to get to Japan. Now he had a real reason to go there, and preaching the Gospel was not it.

“Don't be in such a hurry,” Frank said. “If you really want to go and find her, you'll have to know a lot more Japanese than I do. I was lost.”

“I've picked up a fair amount working at Maneki.”

“Don't make me laugh. You need more than a few set phrases. And you've got to learn to read and write. I see you've picked up a little of the phonetic script, but you have to memorize thousands of characters if you want to read anything. It's murder. After I got back here, I tried to brush up my Japanese and learn the writing system. I took a course at the U.W. but I gave up after a couple of months. I've got to work for a living, I don't have time for flash cards. And even if I did manage to get enough language under my belt, I can't go and live there for months at a time. You're not going to find her in a week or two.”

“I can't wait, though. I'm ready to quit school now, forget about graduating, and just go.”

“Well, how are you going to pay for it? Ask your father for the money? Have you got a trust fund socked away?”

“I could get a job once I got there.”

“I suppose so, teaching English. But that's all you'd be doing all day. You wouldn't have time to study Japanese or do any searching. No, I'm telling you, there's only one way: learn the language here before you go, and get a scholarship to support you while you're there.”

“How long would that take? More than a year, I'll bet.”

“Way more than a year. Four or five, I'd guess.”

“Four or five years? I want to go

now

.”