The Street Of Crocodiles

He was small, unattractive and sickly, with a thin angular body and brown, deep-set eyes in a pale triangular face. He taught art at a secondary school for boys at Drogobych in southeastern Poland, where he spent most of his life. He had few friends outside his native city. In his leisure hours—of which there were probably many— he made drawings and wrote endlessly, nobody quite knew what. At the age of forty, having received an introduction through friends to Zona Nalkowska, a distinguished novelist in Warsaw, he sent her some of his stories. They were published in 1934 under the title of Cinnamon Shops—and the name of Bruno Schulz was made. Three years later, a further collection of stories, with drawings by the author, Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass, was published; then The Comet, a novella, appeared in a leading literary weekly. In between, Schulz made a translation of Kafka's The Trial. It is said that he was working on a novel entitled The Messiah, but nothing has remained of it. This is the sum total of his literary output.

After his literary success, he continued to live at Drogobych. The outbreak of World War II found him there. Together with other Jews of the city, he was confined to the ghetto and, according to some reports, “protected” by a Gestapo officer who liked his drawings. One day in 1942, he ventured with a special pass to the “Aryan” quarter, was recognized by another SS man, a rival of his protector, and was shot dead in the street.

When Bruno Schulz's stories were reissued in Poland in 1957, translated into French and German, and acclaimed everywhere by a new generation of readers to whom he was unknown, attempts were made to place his oeuvre in the mainstream of Polish literature, to find affinities, derivations, to explain him in terms of one literary theory or another. The task is well nigh impossible. He was a solitary man, living apart, filled with his dreams, with memories of his childhood, with an intense, formidable inner life, a painter's imagination, a sensuality and responsiveness to physical stimuli which most probably could find satisfaction only in artistic creation— a volcano, smoldering silently in the isolation of a sleepy provincial town.

The world of Schulz is basically a private world. At its center is his father—“that incorrigible improviser... the lonely hero who alone had waged war against the fathomless, elemental boredom that strangled the city.” Father, bearded, sometimes resembling a biblical prophet, is one of the great eccentrics of literature. In reality he was a Drogobych merchant, who had inherited a textile business and ran it until illness forced him to abandon it to the care of his wife. He then retired to ten years of enforced idleness and his own world of dreams. Father surrounds himself with ledgers and pores over them for days on end—while in reality all he is doing is putting colored decals on the ruled pages; Father who has zoological interest, who imports eggs of rare species of birds and has them hatched in his attic, who is dominated by the blue-eyed servant girl, Adela; who believes that tailors' dummies should be treated with as much respect as human beings; Father who loathes cockroaches to the point of fascination; who in a last apotheosis rises above the vulgar mob of buyers and sellers and, drowning in rivers of cloth, blows the horn of Atonement. . . . Then there is Mother, who did not love her husband properly and who condemned him therefore to an existence on the periphery of life, because he was not rooted in any woman's heart. There are uncles and aunts and cousins, each described with deadly accuracy, with epithets as from a clinical diagnosis.

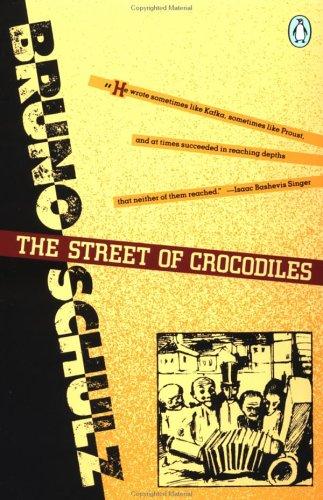

These were Schulz's people, the people of Drogobych, at one time the Klondike of Galicia when oil was struck near the city and prosperity entered it and destroyed the old patriarchal way of life, bringing false values, bogus Americanization, and new ways of making a quick fortune—when the white spaces of an old map of the city were transformed into a new district, when the Street of Crocodiles became its center, peopled with a race of rattleheaded men and women of easy morals. The old dignity of the cinnamon shops, with their aroma of spices and distant countries, changed into something brash, second-rate, questionable, slightly suspect.One could continue to quote from the stories: somebody might perhaps attempt a psychoanalysis of Schulz on the basis of his writings. Polish and other critics have drawn attention to the influence that Thomas Mann, Freud, and Kafka exercised on him. This may or may not be true: although it is also said that Schulz first read The Trial when the book was sent to him for reviewing after the publication of Cinnamon Shops. What is undoubtedly true is that the atmosphere of both Kafka's and Schulz's lives in their respective provinces is not dissimilar. These distant outposts of the former Austro-Hungarian empire, with the memories of the “good” Emperor Francis Joseph still a living tradition, looked up to Vienna as the center of cultural and artistic life much more than to Prague or Warsaw.But whether or not these derivations existed in fact does not really matter, the stories still speak for themselves in the same voice as in the 1930s and there emerges from them in a sunken world, lost forever under the lava of history, an ordinary provincial city with ordinary people going about their daily tasks, a city scorched by the hot summers of every school child's holidays, sometimes shaken by unexpected high winds from the mountains, but mostly sleepy and lethargic—here brought to life by the magic touch of a poetic genius, in a prose as memorable, powerful and unique as are the brushstrokes of Marc Chagall.

On November 19,1942, on the streets of Drogobych, a small provincial town that belonged to Poland before World War II (and now is in the U.S.S.R.), there commenced a so-called action carried out by the local sections of the SS and the Gestapo against the Jewish population. This was a relatively minor incident in an enormous genocidal undertaking; the day of November 19, remembered by a few surviving inhabitants of Drogobych as “Black Thursday,” brought death to some one hundred and fifty passersby. Among the murdered who lay until nightfall on the sidewalks of the little town —who lay where the bullets reached them—was Bruno Schulz, a former teacher of drawing at the local high school. In vain had Polish writers, together with underground organizations, attempted to come to his rescue while he was still alive. They had furnished him with false papers and money to enable him to escape and hide in a safe place, but an attempt to escape was never made. At night, under cover of dark, a friend of the dead man carried his body to the nearby Jewish cemetery and buried him.

No trace remains of that cemetery, and the manuscripts of Schulz's unpublished works, given to someone for safekeeping, are lost. They disappeared along with their custodian. Thus perished, with a portion of his literary oeuvre, one of the finest Polish writers of our century.Bruno Schulz was the author of two books published before the war—Cinnamon Shops (1934), which has been translated into English and published under the title The Street of Crocodiles, and Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass (1937)—works that were recognized immediately by the Polish literary critics and honored by the Polish Academy of Literature, although they were discovered by the world only many years later. The literature of reborn Poland in the twenty-year period between the two great wars abounded in outstanding authors such as Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz and Witold Gombrowicz, who are today widely known and translated into many languages, but first and foremost is Schulz, who is a phenomenon thoroughly apart in the sphere of Polish literature. In its outline the biography of Bruno Schulz appears unassuming and bare. This bard of his native town never left the streets of Drogobych for long. For almost twenty years he worked there as a teacher of drawing and handicrafts, otherwise leading the life of a recluse and maintaining contact with those near to him through letters. In this way he alleviated his isolation without having it disturbed by any outside presence. These letters to his friends, so few of whom survived the war, were in fact the genesis of his writing; for a period they constituted his sole literary activity. In other respects the topography of his life's journey is uneventful. His art grew out of his perceptions of his native town and his childhood.

He was born July 12, 1892, into a merchant family. His father, Jakub, was a bookkeeper and owner of a dry-goods shop, a shop that later was to become in the son's writing the repository of an elaborate fantasy, the sanctum of Schulzian mythology. This mythic resurrection of the shop and the reconstruction of childhood with all its emotional riches would take place only after the father and the business were long gone.

Schulz's Drogobych was a town in Galicia, a province of the Austro-Hungarian empire, which more than a hundred years earlier had helped to eradicate Poland from the map of Europe. In this part of the conquered land Bruno Schulz—the youngest of three children, educated at home and in a school named after Emperor Francis Joseph—did not grow up in the dominant traditions of German-speaking Austria, nor did he remain in the sphere of traditional Jewish culture. The merchant profession to which his parents belonged separated them from the Hasidim, and he was never to learn the language of his ancestors. Bruno Schulz did know German fluently, but he wrote in Polish, the language nearest to him and most obedient to his pen.

When Poland regained independent statehood in 1918, Schulz was twenty-six years old and had had three years of study—discontinued just before the war—in architecture. He taught himself to draw and produced graphics, intending to gain proficiency in this field and make it his career. His work in fine arts gave evidence of considerable talent but enabled him only to obtain— and with difficulty, at that—the post of a drawing-master in a high school. His ideas for fiction date from the 1920s. They mark the beginning, with a delay of some years yet before his publishing debut, of the life of Schulz the writer, who was to find the duties of a teacher utterly repugnant, although that job furnished his sole means of support.In the days crammed with lessons he devoted his free moments to conversing with friends about art—not with the local friends he met daily and who never even suspected him of literary aspirations, but with those distant correspondents living in other cities who were confidants of his dialogues on art. These epistolary conversations provided him for years with his only real spiritual contact with other people. For a long time he did not let anyone know of his literary efforts; it was only drawing and painting that he practiced openly, in full view of his friends, despite the obviously masochistic theme of many of his works. His first literary compositions he concealed in a drawer, sharing them with no one.

Lacking the courage to address readers, he tried at first to write for a reader, a recipient of his letters. When at last, around 1930, he found a partner for this exchange in the person of Deborah Vogel, a poet and doctor of philosophy who lived in Lvov, his letters—even then often masterpieces of the epistolary art—underwent a metamorphosis, becoming daring fragments of dazzling prose. His correspondent, greatly excited, urged him to continue. It was in this way, letter by letter, piece by piece, that The Street of Crocodiles came into being, a literary work enclosed a few pages at a time in envelopes and dropped into the mailbox. Surely no other work of belles-lettres has originated in so curious and, at the same time, so natural a manner. A few more years had to pass before—thanks to the support of the eminent novelist Zofia Nalkowska—the resistance of publishers to a work so innovative could be overcome and The Street of Crocodiles could appear in book form. So the book was made available to the public, although it had been conceived and executed with only one reader in mind, the addressee of the letters sent from Drogobych to Lvov. Writing in this way, Schulz could be wholly indifferent to the tastes of the literary coterie and the capricious demands of the official critics. He would experience their pressures later on, and more than once he claimed that they paralyzed him, changing the quiet immediacy of personal communication into work fraught with peril and addressed to the Unknown—and this for one to whom art was a confession of faith, faith in the demiurgic role of myth.

What is this Schulzian mythopoeia, this mythologizing of reality? On what was his artistic purpose to “mature into childhood” based? Childhood here is understood as the stage when each sensation is accompanied by an inventive act of the imagination, when reality, not yet systematized by experience, “submits” to new associations, assumes the forms suggested to it, and comes to life fecund with dynamic visions; childhood is a stage when etiological myths are born at every step. It is precisely there, in the mythmaking realm, that both the source and the final goal of Bruno Schulz's work reside.

From sublime spheres the Schulzian myth sinks to the depths of ordinary existence; or, if you will, what Schulz gives us is the mythological Ascension of the Everyday. The myth takes on human shape, and simultaneously the reality made mythical becomes more nonhuman than ever before. Conjecture easily changes into certainty, the obvious into illusion; possibilities materialize. Myth stalks the streets of Drogobych, turning ragamuffins playing tiddledywinks into enchanted soothsayers who read the future in the cracks of a wall, or transforming a shopkeeper into a prophet or a goblin. Art was to Schulz “a short circuit of sense between words, a sudden régénération of the primal myths.” Schulz said: “All poetry is mythmaking; it strives to recreate the myths about the world.”

Thomas Mann's Joseph and His Brothers, Schulz's favorite work, is an excellent example of the repeated patterns, the stories that return and return in different variations, continually reembodied from the earliest times up to the present day. Mann presents the biblical story “on a monumental scale”; Schulz, incorporating mythic archetypes within the confines of his own biography, unites his family to legend. His major work was to have been the lost novel titled The Messiah, in which the myth of the coming of the Messiah would symbolize a return to the happy perfection that existed at the beginning— in Schulzian terms, the return to childhood.