The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (7 page)

Tarquinius Superbus selected two of his own sons to carry his offerings to the temple of Delphi, and sent Brutus with them as an attendant. After giving the king's offerings, and obtaining an oracle for him, the three young men resolved to question the Pythoness about their own future.

Each gave a present to the priestess. The two princes offered rich gifts, but Brutus gave only the staff which he had used on the journey thither. Although this present seemed very mean, compared with the others, it was in reality much the most valuable, because the staff was hollow, and full of gold.

The young men now asked the Pythoness the question which all three had agreed was the most important. This was the name of the next king of Rome. The priestess, who rarely answered a question directly, replied that he would rule who first kissed his mother on returning home.

Tarquin's sons were much pleased by this answer, and each began to plan how to reach home quickly, and be the first to kiss his mother. Brutus seemed quite indifferent, as usual; but, thanks to his offering, the priestess gave him a hint about what he should do.

Their mission thus satisfactorily ended, the three young men set out for Rome. When they landed upon their native soil, Brutus fell down upon his knees, and kissed the earth, the mother of all mankind. Thus he obeyed the directions of the Pythoness without attracting the attention of the two princes. Intent upon their own hopes, the sons of Tarquin hurried home, kissed their mother at the same moment on either cheek.

The Death of Lucretia

T

ARQUIN

was so cruel and tyrannical that he was both feared and disliked by the Romans. They would have been only too glad to get rid of him, but they were waiting for a leader and for a good opportunity.

During the siege of a town called Ardea, the king's sons and their cousins, Collatinus, once began to quarrel about the merit of their wives. Each one boasted that his was the best, and to settle the dispute they agreed to leave the camp and visit the home of each, so as to see exactly how the women were employed during the absence of their husbands.

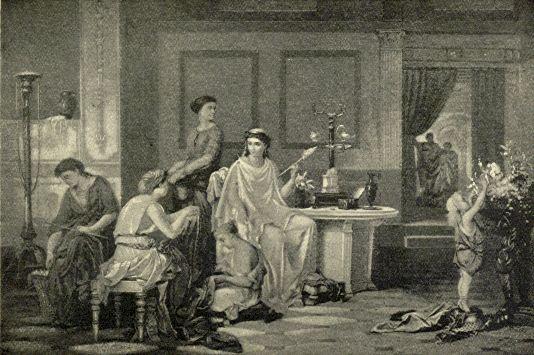

Collatinus and the princes quickly galloped back to Rome, and all the houses were visited in turn. They found that the daughters-in-law of the king were idle and frivolous, for they were all at a banquet; but they saw Lucretia, the wife of Collatinus, spinning in the midst of her maidens, and teaching them while she worked.

Lucretia and her Maids

This woman, so usefully employed, and such a model wife and housekeeper, was also very beautiful. When the princes saw her, they all said that Collatinus was right in their dispute, for his wife was the best of all the Roman women.

Lucretia's beauty had made a deep impression upon one of the princes. This was Sextus Tarquinius, who had betrayed Gabii, and he slipped away from the camp one night and went to visit her.

He waited till she was alone, so that there might be no one to protect her, and then he insulted her grossly; for he was as cowardly as he was wicked.

Lucretia, as we have seen, was a good and pure woman, so, of course, she could neither tell a lie, nor hide anything from her husband which she thought he should know. She therefore sent a messenger to Collatinus and to her father, bidding them come to her quickly.

Collatinus came, accompanied by his father-in-law and by Brutus, who had come with them because he suspected that something was wrong. Lucretia received them sadly, and, in answer to her husband's anxious questions, told him about the visit of Sextus and how he had insulted her.

Her story ended, she added that she had no desire to live any longer, but preferred death to disgrace. Then, before any one could stop her, Lucretia drew a dagger from the folds of her robe, plunged it into her heart, and sank dead at her husband's feet.

Of course you all know that self-murder is a terrible crime, and that no one has a right to take the life which God has given. But the Romans, on the contrary, believed that it was a far nobler thing to end their lives by violence than to suffer trouble or disgrace. Lucretia's action was therefore considered very brave by all the Romans, whose admiration was kindled by her virtues, and greatly increased by her tragic death.

Collatinus and Lucretia's father were at first speechless with horror; but Brutus, the supposed idiot, drew the bloody dagger from her breast. He swore that her death should be avenged, and that Rome should be freed from the tyranny of the wicked Tarquins, who were all unfit to reign. This oath was repeated by Collatinus and his father-in-law.

By the advice of Brutus, Lucretia's dead body was laid on a bier, and carried to the market place, where all might see her bleeding side. There Brutus told the assembled people that this young and beautiful woman had died on account of the wickedness of Sextus Tarquinius, and that he had sworn to avenge her.

Excited by this speech, the people all cried out that they would help him, and they voted that the Tarquin family should be driven out of Rome. Next they said that the name of the king should never be used again.

When the news of the people's fury reached the ears of Tarquin, he fled to a town in Etruria. Sextus, also, tried to escape from his just punishment, but he went to Gabii, where the people rose up and put him to death.

It was thus that the Roman monarchy ended, after seven kings had occupied the throne. Their rule had lasted about two hundred and forty-five years; but although ancient Rome was for a long time the principal city in Europe, it was never under a king again.

The exiled Tarquins, driven from the city, were forced to remain in Etruria. But Brutus, the man whom they had despised, remained at the head of affairs, and was given the title "Deliverer of the People," because he had freed the Romans from the tyranny of the Tarquins.

The Stern Father

A

LTHOUGH

the Romans in anger had vowed that they would never have any more kings, they would willingly have let Brutus rule them. He was too good a citizen, however, to accept this post; so he told them that it would be wiser to give the authority to two men, called Consuls, whom they could elect every year.

This plan pleased the Romans greatly, and the government was called a Republic, because it was in the hands of the people themselves. The first election took place almost immediately, and Brutus and Collatinus were the first two consuls.

The new rulers of Rome were very busy. Besides governing the people, they were obliged to raise an army to fight Tarquin, who was trying to get his throne back again.

The first move of the exiled king was to send messengers to Rome, under the pretext of claiming his property. But the real object of these messengers was to bribe some of the people to help Tarquin recover his lost throne.

Some of the Romans were so wicked that they preferred the rule of a bad king to that of an honest man like Brutus. Such men accepted the bribes, and began to plan how to get Tarquin back into the city. They came together very often to discuss different plans, and among these traitors were two sons of Brutus.

One day they and their companions were making a plot to place the city again in Tarquin's hands. In their excitement, they began to talk aloud, paying no attention to a slave near the open door, who was busy sharpening knives.

Although this slave seemed to be intent upon his work, he listened to what they said, and learned all their plans. When the conspirators were gone, the slave went to the consuls, told them all he had heard, and gave them the names of the men who were thus plotting the downfall of the republic.

When Brutus heard that his two sons were traitors, he was almost broken-hearted. But he was so stern and just that he made up his mind to treat them exactly as if they were strangers; so he at once sent his guards to arrest them, as well as the other conspirators.

The young men were then brought before the consuls, tried, found guilty, and sentenced to the punishment of traitors—death. Throughout the whole trial, Brutus sat in his consul's chair; and, when it was ended, he sternly bade his sons speak and defend themselves if they were innocent.

As the young men could not deny their guilt, they began to beg for mercy; but Brutus turned aside, and sternly bade the lictors do their duty. We are told that he himself witnessed the execution of his sons, and preferred to see them die, rather than to have them live as traitors.

The people now hated the Tarquins more than before, and made a law that their whole race should be banished forever. Collatinus, you know, was a most bitter enemy of the exiled king's family; but, as he was himself related to them, he had to give up his office and leave Rome. The people then chose another noble Roman, named Valerius, to be consul in his stead.

When Tarquin heard that the Romans had found out what he wanted to do, and that he could expect no help from his former subjects, he persuaded the people of Veii to join him, and began a war against Rome.

Tarquin's army was met by Brutus at the head of the Romans. Before the battle could begin, one of Tarquin's sons saw Brutus, and rushed forward to kill him. Such was the hatred these two men bore each other that they fought with the utmost fury, and fell at the same time never to rise again.

Although these two generals had been killed so soon, the fight was very fierce. The forces were so well matched that, when evening came on, the battle was not decided, and neither side would call itself beaten.

The body of Brutus was carried back to Rome, and placed in the Forum, where all the people crowded around it in tears. Such was the respect which the Romans felt for this great citizen that the women wore mourning for him for a whole year, and his statue was placed in the Capitol, among those of the Roman kings.

The Roman children were often brought there to see it, and all learned to love and respect the stern-faced man with the drawn sword; for he had freed Rome from the tyranny of the kings, and had arranged for the government of the republic he had founded.

A Roman Triumph

A

S

Brutus had died before the battle was even begun, the command of the Roman army had fallen to his fellow-consul, Valerius, who was an able man. When the fight was over, the people were so well pleased with the efforts of their general that they said he should receive the honors of a triumph.

As you have probably never yet heard of a triumph, and as you will see them often mentioned in this book, you should know just what they were, at least in later times.

When a Roman general had won a victory, or taken possession of a new province, the news was of course sent at once to the senate at Rome. If the people were greatly pleased by it, the senate decided that the victorious commander should be rewarded by a grand festival, or triumph, as soon as he returned to Rome.

The day when such a general arrived was a public holiday, and the houses were hung with garlands. The Romans, who were extremely fond of processions and shows of all kinds, put on their festive attire, and thronged the streets where the returning general was expected to pass. They all bore fragrant flowers, which they strewed over the road.

A noisy blast of trumpets heralded the coming of the victor, who rode in a magnificent gilded chariot drawn by four white horses. He wore a robe of royal purple, richly embroidered with gold, and fastened by jeweled clasps on his shoulder; and in his hand he held an ivory scepter.

On the conqueror's head was a crown of laurel, the emblem of victory, and the reward given to those who had served their country well. The chariot was surrounded by the lictors, in festive array, bearing aloft their bundles of rods and glittering axes.

In front of, or behind, the chariot, walked the most noted prisoners of war, chained together like slaves, and escorted by armed soldiers. Then came a long train of soldiers carrying the spoil won in the campaign. Some bore gold and silver vases filled with money or precious stones; others, pyramids of weapons taken from the bodies of their foes.

These were followed by men carrying great signs, on which could be seen the names of the cities or countries which had been conquered. There were also servants, carrying the pictures, statues, and fine furniture which the victor brought back to Rome. After the conqueror's chariot came the victorious army, whose arms had been polished with extra care for this festive occasion.

The procession thus made its solemn entrance into the city, and wound slowly up the hill to the Capitol, where the general offered up a thanksgiving sacrifice to the gods. The victim on the occasion of a triumph was generally a handsome bull, with gilded horns, and decked with garlands of choice flowers.

Servants were placed along the road, with the golden dishes in which they burned rare perfumes. These filled the air with their fragrance, and served as incense for the victor, as well as for the gods, whom he was thought to equal on that day.

A Roman Triumph

(continued)